A New, Perhaps Not-All-That-Different Bernie Sanders

What the Democrats may be waiting for

I’ve been writing more about politics than usual lately, which is surprising to me. Actually I’m paying somewhat less attention to politics than I have sometimes, largely because politics is so incredibly depressing. (If you want both a wonderful expression of that feeling, and a wonderful response, check out my fellow Substacker Damon Linker’s latest post.)

For those among my readers who are also frustrated by that emphasis, good news! I’m going on vacation for two weeks starting Sunday, so inasmuch as there’s anything here next week or the week after, it will be something I teed up in advance, and therefore highly unlikely to be something particularly topically political.

But for today: more about politics!

Two weeks ago I had a piece in The New York Times about the so-called One Big Beautiful Bill Act asking what the Republicans could possibly have been thinking passing such an awful and unpopular piece of legislation. That piece focused on the substantive side of the question—what might they be trying to achieve—and was in some ways a development of thoughts I aired earlier on this Substack back in March. The most compact version of the argument is: Republicans aren’t all stupid, and at least some of them know we are headed for a fiscal crisis if we don’t change the balance of spending and taxes in a fundamental way. But they’d prefer to make that crisis more acute if it means they can also make it more likely that the ultimate solution to the crisis is more favorable to Republican priorities and interests than it would otherwise have been, which the law may possibly have achieved. It’s a game of fiscal chicken, and the Republicans just slammed the accelerator.

There’s also the political side of the question, though: why don’t Republicans worry more that the bill will cost them their jobs? I was asked a version of that question on a radio show last week on WCPT 820 (my segment starts at 26:40), and the answer I gave was that Republicans may be resigned to losing the House because of a normal thermostatic backlash, but much less worried about the Senate. Why? Because Democrats are so unpopular as a party in the states they’d need to compete in to ever capture the Senate again—states like Texas and Florida and Ohio and Iowa and Alaska and Kansas—that Republicans can do extremely unpopular things and still win reelection relatively easily. Seriously: in 2026 Democrats could hold every seat they are defending and also pick up Maine and North Carolina, each of which is going to be a tough race to win, and we’d still have a 51-49 Senate. This is not about the map—the map looks great for the opposition party. The problem is that the opposition party is the Democrats.

Honestly, though, I think even that paints too rosy a picture of things from a Democratic Party perspective, because the Democrats are far from assured of picking up the House. Indeed, right now, as Harry Enten explains, Democrats are far behind where they were in 2005 or 2017, and if the election were held today Republicans would be expected to gain 12 seats. How can that be when the Trump administration is increasingly unpopular, with the public turning sharply against it on the economy, foreign policy, even immigration which had been its strongest issue, and with the public negative on the direction of the country, negative on the Republican Party and extremely negative on Congress?

The answer, of course, is that the Democratic Party is viewed even more negatively than either President Trump or the Republican Party.

The negativity is broad and deep, encompassing moderates, liberals and far-left types alike, and both highly-engaged and less-attached voters. Everyone has their own hobby horse to ride about what caused the Democratic Party to lose in 2024—from persistent inflation to the enormous surge in asylum claims to the combination of the Ukraine and Gaza wars to an alienating set of cultural commitments—and I’m sure all these played a role. Add to this the catastrophe of Biden’s unfitness for office—which was far more manifest than I imagined it could have been, and which revealed essentially the entire party infrastructure and much of the press to be either liars or self-deluding—and what they add up to is a large majority of the country who simply no longer trust the Democratic Party at a fundamental level, even if they agree with it substantively on many issues.

I really don’t think that is something that can be fixed by tweaking the policy mix or better messaging, nor even, quite often, by doing a better job, because we don’t all agree on what “a better job” looks like, and without trust to bank on you probably won’t have time to demonstrate that you are doing a better job before the rug is pulled out from under you. I think it’s going to take something much bigger to turn things around.

Mind you, I’m not saying that it’s impossible for the Democrats to win any elections without rebuilding trust. If Trump does something that finally and truly breaks the economy, all bets are off. Ditto if he loses a war in humiliating fashion. Elon Musk’s third party dreams could wind up playing less like Ross Perot against George H. W. Bush and more like Nigel Farage against the Tories, particularly if this Epstein business winds up detaching a chunk of MAGA from Trump, and delivering the country to the Democrats on the back of a weak plurality such as brought Keir Starmer to 10 Downing Street. For that matter, Democrats could possibly just grind out a narrow win in the House in 2026 and in the White House in 2028 by playing it safe and smart. There are a variety of plausible scenarios that could put Democrats back in power at some point in the next few years without anything radical changing about the Democrats themselves.

But I don’t think they’ll win back the public trust if they win power any of those ways, and without public trust any stay in power will be extremely evanescent—and what succeeds them will be worse even than what we’ve already seen. Right-wing populism thrives on the perception that the system is broken, which is why the collapse of trust in both the Democrats and the old Republican Party has been like jet fuel for right-wing populism. Democrats can position themselves as technocratic reformers who promise to fix the system and make it work more efficiently, or as left-populists who promise to make it work for the people rather than the powerful, or they can just run (as they did in both 2020 and 2024) on “we promise not to blow everything up.” But they can’t capitalize on the currents of nihilism and civic despair that have grown so powerful. That dark path is only available to the other team, if they choose to go down it, as, in their current incarnation, they have.

So what can the Democrats do? Given the depth of the hole they are in, I don’t think they can really come back without a revolution within their own ranks. I listen to someone like Elissa Slotkin—a politician with solid political instincts—calling on Democrats to reclaim their alpha energy, and I search in vain for signs of that energy in her own words. Does she take any notably firm stands herself in that interview? Does she name names? Is she willing to make enemies? You want to know what alpha energy looks like? In 2016, Donald Trump had alpha energy. He was flagrantly disloyal to both the substantive positions his party had taken and to the interests of that party as an institution, and openly declared his intention to remake the party in his own image—which, regardless of whether he has actually governed the way his supporters imagined he would, he emphatically has done.

The Democratic Party today looks to me an awful lot like the Republican Party did then. The GOP had faced a series of revolts from its right wing that had seriously damaged its brand and cost it winnable races, but that right wing remained the overwhelmingly dominant force within in the party. Only Donald Trump could square that circle and come up with a (barely) winning formula. The Democratic Party today is much more liberal than it used to be when it could seriously contest for power in all regions and for all branches of government, something I’ve been writing about for years and which seriously inhibits the party from even embracing a big tent much less running to the center. Because of that, Matt Yglesias’s conclusion in his post today may well be right: that ultimately the progressive wing is going to have to take over the party and learn the hard way that some of its core ideas are some combination of wrong and unpopular. But that could take quite a while. The only way I can see to short-circuit that lengthy process is for someone to pull off the Trump 2016 trick of running simultaneously as an extremist and as a moderate, but always as the emphatic avatar of what the core of the party actually believes. Winning that way would reveal both that those beliefs are more flexible than most observers thought and the existing infrastructure of power in the party was built on sand, because they are completely out of touch. It would give whoever that person is the trust to do what was necessary, even when that isn’t what the self-proclaimed arbiters of orthodoxy claim must be done—even when it isn’t what they themselves ran on.

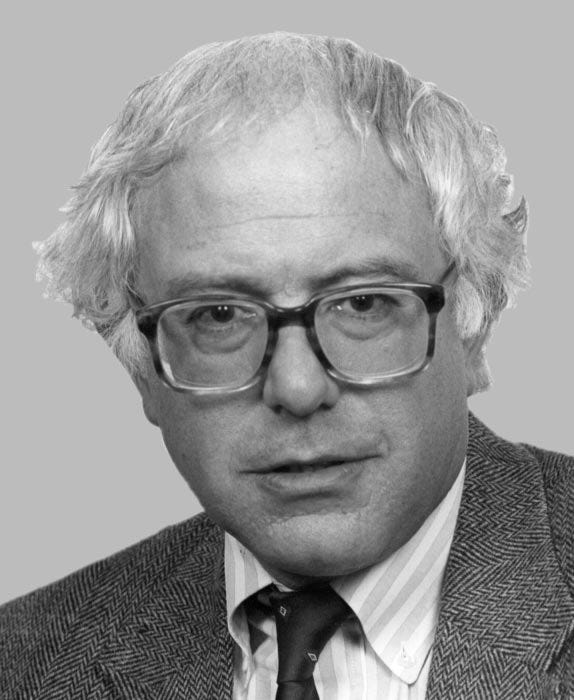

What it may take, in other words, is a new—and perhaps not all that different—Bernie Sanders. Not in the sense of a full-spectrum leftist, but in the sense of someone who is emphatically not beholden to the party infrastructure, and who establishes their credibility via a profound emotional bond with the party’s core voters, and on the basis of that bond vanquishes the structures and institutions of the party and remakes it in his—or her—image.

People like that don’t grow on trees, though. And it’s a depressing thought that the long-term survival of American liberal democracy depends on certain personal characteristics and a style of politics that resemble those of the man who has proved to be liberal democracy’s greatest domestic threat.