Can a Collapsing Center Be Recaptured?

It's not 1992 anymore

As I mentioned in my most recent wrap-up, Kevin Drum had a corker of a piece last week titled “If you hate the culture wars, blame liberals.” Needless to say, this did not go over super well with liberals.

The argument in the piece is fairly straightforward. On a variety of issues over the past 30 years, the Democratic Party has moved further to the left than the country as a whole, while the Republican Party has sometimes moved left, sometimes right, sometimes stood still. As a result, the Democrats are now marooned way off of the country’s natural center of gravity, are decreasingly even capable of speaking to the country as a whole, and hence are barely able to cobble together a national governing majority under the most favorable circumstances.

On one level, this is clearly correct. Barack Obama’s views on crime, immigration, gay rights, and so forth would today put him notably to the right of the Biden Administration, and Biden ran in 2020 as a relative moderate within the Democratic field. Moreover, it’s not just a matter of changes of views; there’s been a notable change in style on the left since some time in the middle of the Obama years, a stridency wasn’t so prevalent before.

But on another level, it’s kind of a banal result. Structurally, the left is always going to be pushing the country to change. That’s kind of what it means to be on the left. If they’ve succeeded in bringing a big chunk of the country along with them, that’s evidence of success. Perhaps the left needs to moderate a bit to recapture the center and win more elections, but it’s somewhat perverse to compare the left’s ideological drift leftward to aggression in a war.

Nonetheless, that’s not my real concern with the piece’s analysis or the recommendations that come out of it. What’s missing is a full understanding of the right’s reaction, and the implications of that reaction for the plausibility of recapturing the center. Drum describes that reaction as fundamentally defensive, and it is true that people generally have stronger and more visceral reactions to fear of loss than the prospect of gain. But why did they think they were going to lose? If the left moved too far leftward, such that they began to lose elections, that should rationally have prompted the right to move left as well, and win. Then, from the vantage point of victory, they could use that newfound power to start pulling the country back rightward.

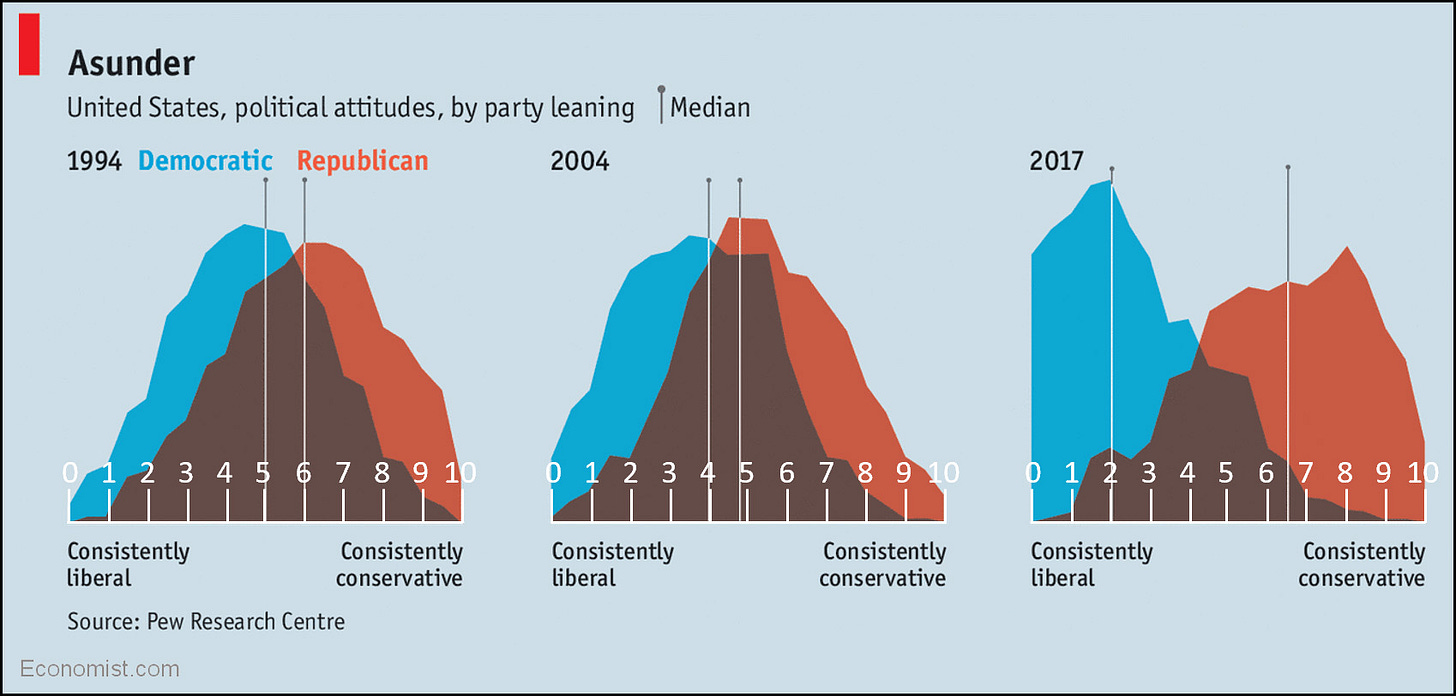

Take a look at the graphic from The Economist that Drum included in his post, and you’ll see that this is precisely what the GOP did from 1994 to 2004:

In 1994, the distribution of the two parties’ voters looked like overlapping bell curves. Most people fell in the center of the distribution in each case, with far fewer out on either extreme, and the two centers weren’t far apart. From 1994 to 2004, the shapes stayed very similar, but both centers moved left, because the country as a whole had moved left. This is exactly what you’d expect if the Median Voter Theorem were operative, and the Bush-era GOP was pursuing precisely the strategy I described of recapturing the center and then aiming to pull it rightward, spending more money on education and health care but also promoting a more religious conception of American identity and a more aggressive foreign policy.

But I want to note something else at this point. The term “culture war” dates from a 1992 speech at the GOP convention by Pat Buchanan, a major antecedent of Trumpist political themes. In 1994, Newt Gingrich led the GOP to a sweeping Congressional victory rooted in reaction against the supposedly extreme and dangerous Bill Clinton administration. In 1998, Republicans in Congress impeached Bill Clinton. In 2000, we had a virtual tie for the presidency that was heavily contested in the courts by both parties, after which many Democrats believed George W. Bush illegitimately assumed the presidency. In 2002, President George W. Bush led the Republicans to a rare midterm victory on the back of a campaign heavy with the insinuation that the Democrats were insufficiently patriotic. And in 2004, a major “get out the vote” motivator for his base was his advocacy of a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage.

My point is not to say “see: the GOP started it!” My point is that the culture war started at a time when both parties’ voters were normally distributed and their respective centers of gravity were pretty close together, and was prosecuted vigorously for over a decade without notably changing that distribution. Politics was sometimes ugly and sometimes scary and sometimes extreme, but in fact there was enormous overlap between the views of the actual voters that the two parties were trying to mobilize, and politics also reflected that fact.

The right’s behavior began to diverge from this path during the Obama years. The graphic doesn’t show the 2011 or 2014 data, but it’s available from Pew, and what it shows is that between 2004 and 2011 the shape of the Democratic Party’s political coalition changed basically not at all, while the Republican Party moved roughly a point to the right on the survey’s ten-point scale—back to where it was in 1994. Then from 2011 to 2014, both parties moved away from the center, with the Republicans moving nearly another point to the right while the Democrats moved to the left. An unmatched Democratic lurch leftward didn’t happen until the period around the 2016 election.

I don’t think it makes much sense to talk about that sequence as simply a story of Democratic aggression in a culture war. Rather, as Damon Linker argues in a very smart follow-up piece to Drum’s, it’s fundamentally a story of the center not holding. And I remember pretty well the sequence by which it failed to hold. After the disaster of the Bush administration and the election of Barack Obama with an overwhelming Democratic majority in both houses of Congress, the Republican Party’s base moved right and stayed there. This wasn’t primarily a reaction to the Democrats moving left; it was a reaction to their own policy and political failure during the Bush years. This more right-wing GOP was able to win the bulk of state legislatures and the House of Representatives in 2010 and the Senate in 2014, and even though it was unable to muster a national majority in 2012, from that posture of resistance they were able to frustrate Democratic goals sufficiently to convince an increasing proportion of the Democratic base that there was no point in seeking common ground, and instead to move left as the GOP had moved right.

So that’s where we are today: in a world where there are simply far fewer voters in the center to be captured by either party. In 2004, the overwhelmingly most common scores were 4 or 5 on Pew’s ten-point scale—most voters were in the center, with some a bit more left and some a bit more right. In 2017, there were more voters with a score of 2 than a score of 4 or 5—but also nearly as many with a score of 8. The parties have sorted themselves more fully in ideological terms than they had before, but individuals themselves have sorted themselves more ideologically, with fewer cross-pressured voters who hold liberal views on some issues and conservative views on others. There still are voters in the center, and they are still divided about evenly between the two parties. But there are fewer of them, and they are now a distinct minority in both parties, where previously they were a majority.

The advice that both Drum and Linker give to the Democrats is to moderate somewhat in the interests of recapturing the center. But if there is no center, that’s a pretty tall order. It’s one thing to nominate McGovern or Dukakis, realize that their coalitions are simply too small to win, and then move back to the center where the votes are. But the core of the Democratic coalition has moved left; that’s where the votes are. Moderating would be moving away from the party’s natural center toward its periphery. How exactly do you do that without moving that natural center itself, which means convincing your own voters that some of the liberal views they now hold are not just unlikely to win majority approval, but wrong?

I don’t see that happening. Which means that until that evolution happens on its own (which it might), the challenge for Democrats is how to make those centrist or cross-pressured people who remain feel comfortable in a party whose center of gravity is inevitably going to be well to their left. If the median Democrat is a 2 on Pew’s scale, then even if Democrats capture a larger share of 4s and 5s, those people will be significantly outnumbered within the Democratic coalition. The fact that many of those people do feel willing to vote for Republicans despite the fact that the Republican center of gravity is significantly to their right should suggest that it is possible for Democrats to do the same. But I don’t think that it’s going to be easy.