Will Multipolarity End Before It Has Begun?

Thoughts on President Biden's visit to Kyiv and Wang Yi's visit to Moscow

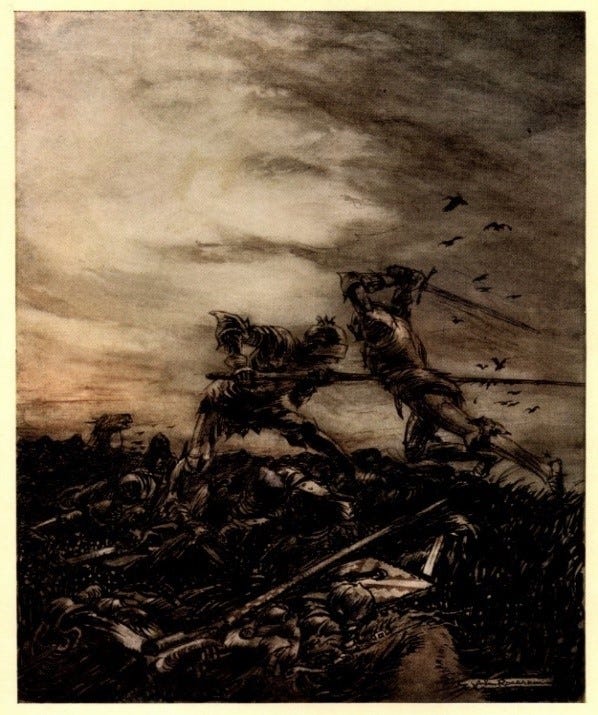

How Mordred was slain by Arthur, and how by him Arthur was hurt to the death. By Arthur Rackham, 1917

There’s a certain kind of foreign policy analyst for whom the prospect of getting just about every country in the world to line up on one side or another of some grand conflict is profoundly appealing. These are the kinds of folks who cheer for the idea of an “alliance of democracies” that would supersede both NATO and the U.N. because it would express “moral clarity.” That impulse was memorably expressed in the famous speech by President George W. Bush that called Iraq, Iran and North Korea an “Axis of Evil,” an attempt to shoehorn the War on Terror into the framework of World War II, incidentally forgetting that our most important ally in that war was the Soviet Union, or perhaps of the Cold War, incidentally forgetting the numerous dictatorial regimes we supported, sponsored and created in our efforts to stop the spread of Soviet influence.

I’m starting to worry a bit that these folks might finally get what they want. If they do, none of us are going to like it.

My worries are prompted by President Biden’s unexpected visit to Kyiv today to reassure that country and its government that the United States is committed to supporting them for the long term. That visit is symbolically dramatic but it doesn’t signify a change in policy, nor that Ukraine is being given a blank check. Remember: it was only a few days ago that this very same administration was planting stories in the press about how the United States isn’t committed to a total Ukrainian victory, and isn’t going to give them all the offensive weapons they want. But it is a clear signal, and that signal is that the United States is prepared to support Ukraine through a long war of attrition—which is what we look likely to get. If Russia ever comes to its senses and comes to the table with a reasonable peace proposal, you might see daylight peek through the cracks between the American and Ukrainian positions. But so long as that is not the case, this administration is saying, the United States isn’t going to pressure Ukraine, either directly or indirectly through a slackening of assistance; we’re going to stay the course, as long as it takes.

So far that policy of calibrated support, designed to keep Ukrainian resistance alive and allowing the Russians to dig their own numerous graves, has proved remarkably effective. The war is daily demonstrating that Russia’s massive advantage in manpower and GDP is no match for the superiority of Ukrainian national pride armed with NATO weapons and training, and America is getting that demonstration for a bargain price in the grand scheme of things.

But we’re not the only country that can play that game. Iran has emerged as a major supplier of drones to Russia, which has not only significantly bolstered Russia’s war effort but no doubt enhanced the reputation of Iran’s own military capacity (much as Turkey’s drones did for that country when they were deployed in the most recent Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict). Now, in a much more significant development, China appears to be heading in the direction of supplying Russia with military assistance, including lethal assistance. China’s productive capacity is unparalleled; if China does indeed step up to make sure Russia never runs out of ammunition, it’s hard to see how Russia could outright lose a war of attrition with Ukraine. The burden would fall on Kyiv to change the dynamic on the battlefield, which is a much taller order than letting the Russian army destroy itself.

That’s not the most worrisome thing to me about this development, though. What worries me most, rather, is the degree to which it implies a firming up of the lines of alliance. The United States is already wielding Iranian military support for Russia as a justification for keeping nuclear negotiations with that country on ice, even as the country edges closer to the nuclear threshold. The prospect of some kind of military conflict with Israel has surely increased. Meanwhile, if China does wind up supplying Russia with weapons, it would be a remarkable development not so much because of what it would do to U.S.-China relations—those continue on their downward spiral, which is precisely what one would expect after the United States all but declared war on China’s semiconductor industry—but because of what it might do to Sino-European relations. I can’t think of anything better-calibrated to help the United States win Europe to its side in its confrontation with China than direct Chinese assistance for Russia’s war in Ukraine. If that hasn’t been an important consideration for the Chinese, it’s an indication of just how far down the road to globally polarized conflict we may already have gone.

I worry about that development for many reasons. For one thing, it means that any regional or local conflict could potentially be polarized. That’s certainly how things played out during the Cold War, with ruinous consequences across the Global South. Far from providing “moral clarity,” global polarization will encourage the United States to prioritize alignment over matters like human rights or democratic character. This has always been the case to some degree, but the more polarized the international environment becomes, more certain it is.

But my biggest concern is that a bipolar system is fundamentally unstable, prone to unpredictable escalatory spirals. We’ve mostly forgotten that fact because during the Cold War we managed never to climb all the way up the ladder to catastrophe, but we’ll never know how much of that was a feature of the fundamental irrationality of strategic nuclear exchange, how much of it was due to the Sino-Soviet split, and how much of it was just dumb luck. A world in which the United States faced the challenge of a rising China, but wasn’t sure of Europe’s own commitment to meeting that challenge and naturally assumed that India and Russia would always be looking out for their own advantage first and foremost, is a world that would only get more difficult for the United States to maneuver in. It would involve a lot of nimbleness and tough choices between conflicting objectives. But exactly the same thing would have been true of China in that world, once the United States had decided to meet their challenge (which we hadn’t started to do really until the mid-2010s); they would have had to weigh every decision not only in terms of how it affected their competition with America, but in terms of what advantages it might give to third parties eager to take advantage. By contrast, a world in which everything lines up is a lot neater, a lot simpler. It’s also a lot more dangerous.

Of course the world isn’t all lined up yet. South Asia, South America, Africa—most of the global South has tried to stay out of Russia’s war against Ukraine, and much of it will no doubt try to stay out of the conflict with China as well. But things are certainly trending away from multipolarity and toward a new bipolarity. I suspect that feels good to a lot of people. I worry about that most of all.