Armageddon Wrap

Thinking again about the unthinkable

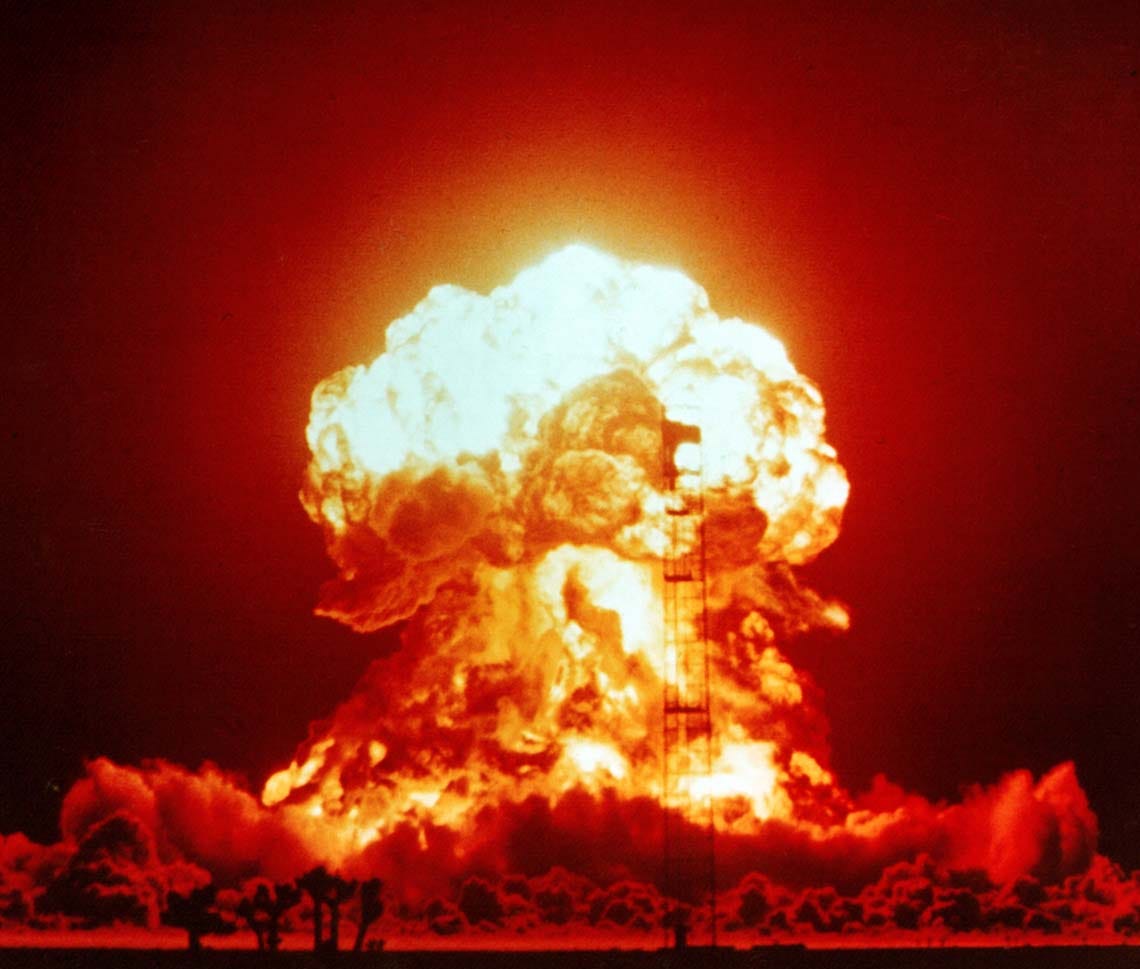

I last touched on the cheery subject of nuclear holocaust back in March, when I made a series of analogies between the risk of a general nuclear exchange and the risk of global financial meltdown, pointing out how difficult it is to get a handle on either kind of risk. Given that difficulty, it’s rational generally to ignore that extreme tail risk entirely, since it doesn’t rationally affect mundane calculations, but ignoring it can readily contribute to increasing that tail risk, such that you create the very irrational catastrophe that you nominally aim to prevent. I stand by that analysis as far as it goes. Now that the risk of nuclear war is back in the news, though—in the wake of Russia’s annexation of four Ukrainian oblasts, Ukraine’s declaration that they would seek NATO membership, and Russia’s alarming nuclear saber-rattling—it feels worth a revisit.

My first inclination is to stick with my original viewpoint, and say that references to movies from the 1980s seem entirely apropos:

But for better or worse, the option of “not playing” was taken off the table a very long time ago. We’re in the game, and the question is what the next play is given what the other players have been saying and doing.

So what have they been saying and doing?

Russia, obviously, has made it clear that it now considers the parts of Ukraine it annexed to be Russian territory, and that therefore it is prepared to defend them as it would defend Russia proper, including with the use of nuclear weapons. But it’s not totally clear what this means in practice for two large reasons. First of all, Russia does not currently control all of the territory that it annexed—indeed, it is currently retreating from Lyman which is in the Donetsk Oblast. It’s one thing to draw a line in the sand and promise terrible consequences if the line is crossed; it’s something else to draw the line behind where the other guy is already standing. We’ve obviously moved from deterrence or escalation dominance to some other realm entirely. Second, it is not clear how nuclear weapons could be used effectively to “defend” those territories from attack. As I argued back in May, the classic proposed tactical use for small nuclear weapons is to destroy masses of advancing enemy armor. But is there any such target in Ukraine? I remain skeptical. The most plausible military targets to threaten with nuclear weapons would by NATO bases from which Ukrainian forces are being resupplied, but such an attack would be such an obvious and massive escalation that it’s hard to imagine even a desperate Putin resorting to it.

Which is why most of the debate has not been about how Putin could actually win by using nuclear weapons, but how and why he might use them anyway even though they couldn’t be used tactically to win the war. That is to say: how they could be used strategically as tools of terror.

This thread gives a good rundown of these kinds of possibilities:

I understand what it means to threaten nuclear weapons use to deter “regime-threatening” developments in war. That’s what Israel’s undeclared policy has been presumed to be for decades: that if the country were in danger of being overrun by invading armies, they would threaten to use nuclear weapons against the invaders’ population centers as a deterrent to force them to stop their advances short of the annihilation of the Jewish state. But, once again, it’s not clear how that case applies to Russia. Inasmuch as Putin views Ukrainian advances as “regime-threatening” this is purely a political matter. Nobody thinks Ukrainian armies are going to take Moscow and install a puppet Russian regime, much less physically obliterate the Russian people. Rather, Putin’s fear is that he, personally—along with his cronies—could not survive a clear defeat in war. That may or may not be true, but it’s simply false to define that as an existential risk for Russia.

So the assumption, then, is that what Putin is really threatening is to use nuclear weapons not tactically to neutralize a military target, but strategically—to wantonly massacre civilians—if he is not allowed to achieve his political aims and thereby salvage his political standing.

Is it possible that he would do that? I don’t know how anyone can say definitively that he would not. But it’s also very easy to see why it would be a problem to accede to any such threat. It’s roughly equivalent to North Korea saying “surrender Seoul at once or we will nuke Tokyo.” I’m not sure precisely what we would do in such a situation—but I’m pretty sure we wouldn’t just surrender Seoul. More to the point, though, it would be up to South Korea whether to surrender or not. In the case of Ukraine, I feel confident saying that they will not stop fighting because Russia is threatening to use nuclear weapons against them. So what Putin is really hoping is that the United States will, in response to these threats, stop helping Ukraine with economic and military aid and with intelligence, and instead lean hard on them to accede to Russia’s demands—which, given the nature of those demands, amounts to surrender.

There is a legitimate argument to make that, in fact, we should have done precisely that long ago, that we should never have given Ukraine any hopes of integration into the West. We should have explained to them back in 2004 that while they were nominally independent, we understood them to be part of Russia’s sphere of influence, and so if Russia made any demands of them they had better accede. That would have been cold-blooded realism, and I can have a reasonable conversation with someone who takes that view, even though I doubt it would have achieved the goals they imagine.

But that’s a version of “the only way to win is not to play.” Now we are in the game. Now, if we radically reverse ourselves in response to nuclear blackmail, we’re opening the door to precisely the North Korean scenario I just described, and in every theater on earth. If Ukraine is ready to keep fighting despite the risk of nuclear attack, and we force them to surrender, you can kiss the entire American nuclear umbrella goodbye. Surely someone in the Kremlin understands that, and understands, therefore, that Putin’s threats aren’t going to magically deliver a Russian victory.

So what is our move? Ideally, we’d want to find a face-saving formula that would allow Putin to climb down from his threats by achieving at least part of his objectives, without it looking like we had given in to nuclear blackmail. But I’m honestly not sure what such a formula might be. In the Cuban Missile Crisis, America quietly offered to remove our missiles from Turkey and to promise not to invade Cuba. Those were tangible wins for Khrushchev, who was primarily worried about his tangible military position more than about his political standing at home. Putin, though, has boxed himself into a corner where what he’s asking for is the total victory that he has been unable to achieve on the battlefield. This excellent column from David von Drehl argues that a negotiated solution “with lines limited to the pre-February status quo” would be far preferable to pressing on toward total victory and a possible collapse of the Russian state—and I readily agree. But where is the evidence that Putin would entertain for even a moment a return to the pre-invasion status quo? He’s threatening nuclear weapons use if he isn’t allowed to keep four Ukrainian oblasts that he doesn’t even hold in their entirety.

All I can offer, then, is the advice that we not try to maintain escalation dominance ourselves by ratcheting up threats in response. We should say—as we have so far—that this is not a time for considering Ukrainian membership in NATO. We should reiterate that we will not intervene directly in the conflict even if we continue to support Ukraine’s own efforts with aid and intelligence. We should treat any Russian use of nuclear weapons not as an attack on the United States or its allies requiring a massive retaliatory response, but rather as an extraordinary war crime, which is what it would be. Most important, we should make it clear that if Russia is losing its chosen war, nuclear terror will not change that fact, and so they ought to negotiate.

President Nixon was the great American advocate of the “madman theory” of diplomacy, but so far as I can tell none of his successful diplomatic maneuvers were achieved in that way, while his more explicitly mad gambits never went anywhere. Nixon briefly considered using nuclear weapons to win the war in Vietnam. Thank God he we didn’t go there, but if he had I feel confident in saying that he would not have won the war with them, but would instead have utterly destroyed America’s global position. But the gestures he did make in the direction of nuclear escalation, such as in Operation Giant Lance, had no demonstrable effect on Soviet behavior. In my opinion, we should aspire to the same sang froid that the Soviets displayed in 1969, and treat Putin’s threats as desperate bluffs rather than signs of actual madness.

And then we had better pray that we are right.

On Here

Just one post On Here this week: Wednesday’s piece about Everything Everywhere All At Once.

But since Yom Kippur is just around the corner, and I’ve written nothing new on that subject, I’ll also link to last year’s post about the holiday, containing within it links to prior pieces of mine that are better than anything I’m likely to come up with this year, along with videos of three seasonal Leonard Cohen songs, of which “Who By Fire” seems singularly appropriate given the subject tackled in the bulk of this post.

May we all be inscribed and sealed for another year in the Book of Life.