Videos of Judith Butler saying that the October 7th massacre of Israelis was an “act of armed resistance” and therefore “not terrorism,” and calling Hamas and Hezbollah “progressive” and “part of the global left” have been making the rounds, and are coming in for predictable mockery. (Here’s my friend and colleague Damon Linker reminiscing about Michel Foucault’s rhetorical support for the Iranian revolution that would have readily executed him were he Iranian). Terrorism is the deliberate use of violence against civilians to further political aims; Hamas and Hezbollah are traditionalist, reactionary religious social movements with explicitly antisemitic aims. How could Butler say—and believe—such obviously absurd things?

The answer, I think, is that people misunderstand the meaning of the word “progressive.” We tend to use the term as a catch-all to mean anyone who has “right-thinking” attitudes about various social causes, which leaves open the question of how they decide what those attitudes are. But once we know what those attitudes are, even if we don’t know how they got that way, surely we can judge progressives for contradicting themselves. Since Butler’s most prominent work is in feminism, gender studies and queer theory, calling the socially reactionary Hamas and Hezbollah “progressive” seems insane—their attitudes are emphatically not “right-thinking” by Butler’s lights!

The question of how “right-thinking” attitudes are decided upon can’t be so simply elided, however, because it explains the apparent contradiction. Progressivism is fundamentally oriented around history. It posits that history has a direction, that the direction can be discerned, and that right and wrong are fundamentally about which “side” of history you are on. You can be more or less moderate, more or less radical in your approach to this question—President Obama, who loved talking about the arc of history and getting on its right side, was a decidedly moderate progressive, while Butler is a decidedly radical one—and the difference between moderation and radicalism will result in different answers to all sorts of questions. The question of how Butler could simultaneously favor radical ideas about gender and support terrorist groups with reactionary views on those same subjects is answered, though, by that orientation around the arc of history.

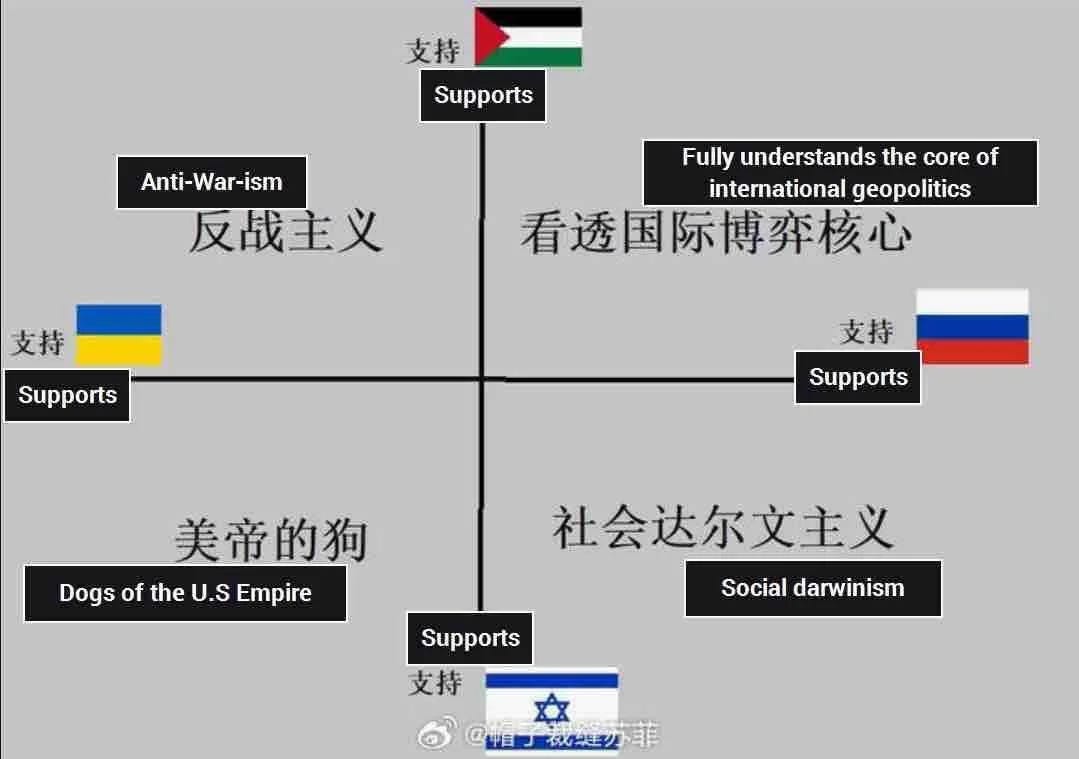

To illustrate what I mean, consider this meme from China that made the rounds some months ago:

Most of the commentary I saw on this meme was either mocking or perplexed, but when I first saw it, I thought: that’s actually quite useful and illustrative of a certain point of view. While the origins of the Russia-Ukraine war and the Israel-Gaza war are very different—Russia attacked Ukraine whereas Israel’s invasion of Gaza was a response to Hamas’s attack on October 7th—that difference pales in comparison to the power differential between the two sides in each case, and to both countries’ relationship to America. Russia is much more powerful than Ukraine, and its war aims are to crush Ukraine, dismember it, and ultimately reduce it to vassal status. Inasmuch as Ukraine sought a more pro-Western orientation, the war is also a kind of proxy war against the United States and NATO. Israel is also much more powerful than Hamas, or than the Palestinians of Gaza more generally, and those disinclined to credit its protestations to the contrary could certainly describe its war aims as not only destroying Hamas but reducing Gaza to impotent vassal status, or possibly even expelling its inhabitants. The ambiguity about Israel’s ultimate war aims is precisely why both the United States and its Arab allies have been increasingly vocal about saying that the war cannot be used as an excuse for ethnic cleansing, and must end with a clear path to a Palestinian state—but America has taken that position not only for moral reasons but because it is the position that potentially reconciles our various allies. This, then, is arguably another proxy war against America.

I know plenty of people who reside in the top left corner of the chart, labeled “Anti-War-ism,” and I understand how they wound up there. They are siding with the weaker side in the conflict, the side that seems to them to be suffering most—and they think the United States should stand with the underdog and act to alleviate suffering. I don’t know a lot of people in the bottom right corner of the chart, labeled “Social darwinism,” but there is certainly a faction within the Republican Party that strongly supports backing Israel while also opposing aid to Ukraine, and a broader sentiment against foreign policy as social work is pervasive on the right—so I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to locate that faction in the bottom right quadrant. The point of the meme, though, is to say that the people in both of these quadrants are confused about the nature of world politics. These kinds of considerations—who is strong and who is weak, who is suffering and who is causing suffering—aren’t what matter. What matters is what side you are on with respect to the “U.S. Empire”—are you with it, or are you against it? If you view American imperialism as the dominant reactionary force in the world, then it makes all the sense in the world for a progressive to support its opponents, regardless of whatever else those opponents stand for.

That, I think, is the right context within which to understand the facially absurd statement that Hezbollah and Hamas are “progressive” or “part of the global left.” If Israel is a Western colonial state, and Western colonialism and imperialism are the greatest reactionary forces, then supporting Israel’s opponents is ipso facto the progressive position, regardless of who those opponents are or what else they stand for. And, if you really want to be consistent about it, that also means that supporting Ukraine—which is backed by NATO, a major tool for American power projection—is non-progressive even though Russia is both the aggressor and the preeminent reactionary power in the world today.

It’s easy (and correct) to mock this kind of thinking, to point out that it inevitably leads to writing songs defending the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, but it’s worth remembering that the opposite approach, one that completely ignores history and practical consequences, and decides questions on a purely facial moral basis, leads to equally absurd results, because there are no pure and uncompromised actors out there on the world stage. Moreover, the conviction that we are the good guys of history, and therefore everyone on our “side” is the good guys, is just as obviously false as the conviction that we are the bad guys and so everyone who opposes us is good. Finally, it’s a legitimate knock to say that nuanced stances are rarely rhetorically effective, and frequently aren’t even heard. We saw an example of that at the Academy Awards on Sunday night, when Jonathan Glazer, director of The Zone of Interest, used his acceptance speech for Best International Feature to denounce the Israeli occupation, the October 7th massacres perpetrated by Hamas, and Israel’s war in Gaza in response as all examples of the consequences of dehumanization, and therefore on a continuum with the Holocaust (the subject of his film). What people heard was that he compared Israel to the Nazis and the war in Gaza to the Holocaust—and therefore that he was either a hero or a traitor. We want very badly to know whose side to be on. We don’t want to acknowledge that the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being. (And, as Solzhenitsyn went on to say, who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?)

Personally, I think the thing to toss from the progressive mix isn’t the belief in the importance of history, much less a morality that is substantially consequentialist, but the belief that history has a direction that one can get on the right side of. History matters a great deal—we will ultimately be judged by it for how we shaped it—but the owl of Minerva takes flight only at dusk. When I look out on the world, I don’t see a “global left” at all—the phrase implies a structure to history that I see no evidence of, and an eschatology I see no reason to believe in. That’s the most important reason why Hezbollah and Hamas can’t be part of it; because it isn’t a thing. I don’t think history is arcing towards a global Islamic revolution either, but at least that’s an eschatology that Hezbollah and Hamas actually believe in. But I also don’t think we’re in a global battle between liberal democracy and authoritarianism—and if we were, those battle lines would cut through Israel’s heart, and through America’s as well, as much as between states. I’m not the Kwisatz Haderach; I don’t know the shape of the future. I only share an increasingly widespread sense of ominous possibility looming.

In that regard, one of the ominous possibilities is precisely that everything will line up again in neatly arrayed sides the way that Chinese meme wants them to, the way, it seems to me, Judith Butler wants them to—and, for that matter, the way the old neoconservatives wanted them to. There are times like that, and when they have passed, a lot of people remember them for their moral clarity and their sense of purpose. In the midst of them, though, they are times of tremendous suffering. So I hope that’s not where we’re headed. And to the extent that I can labor—intellectually, in my small and surely ineffectual way—against going there, that’s what I’m going to do.

A bit of home news, even though I didn’t title this post a wrap.

First, the Academy Awards were last night, so perhaps nobody wants to talk about 2023’s movies anymore, but my latest piece at Modern Age is up now on their new website, and it’s about the plethora of prominent “great man” biopics that came out last year, most of which I thought were failures. Most of the piece actually treats two exceptions to that, though. Killers of the Flower Moon, which came up empty on Oscar night, isn’t a “great man” biopic at all, but it fails, I think, for not endowing its central character with stature commensurate with the film’s focus. He isn’t an interesting character, so why is the film so interested in him? Oppenheimer, meanwhile, is a “great man” biopic and a successful one—I’m a fan of the film, and glad to see it win the many accolades it did. But a big part of what makes it interesting is the way in which it’s a meditation on the limits of greatness in shaping the world. Anyway, check it out here.

Second, I may be scarce around here for the remainder of the month, as I will be traveling from tomorrow and don’t expect to have the opportunity to post much if at all while I’m away. My apologies, and I will strive mightily to make it up to you all upon my return.

You know people in the upper-left quadrant, and they side with the underdog. Maybe the people you know limit your outlook.

I am in the upper left quadrant because this very common analysis has an inexorable logic:

- Two peoples call a rather small slice of land home

- Forcibly removing either people is a war crime to be avoided at great cost, as is one side controlling the land and denying the other legal and political rights.

- Therefore the two-state solution is the only path that is both feasible and humane. (I understand there are intelligent good faith advocates of a single state with equal rights for all, that is not widely seen as feasible given established hatred).

For decades now both the Israeli government and Hamas have done what they can to prevent two states. The Palestinian Authority deserves much criticism for corruption and poor governance, but they have not wavered in their support for a two-state solution since they accepted Israel as part of Oslo. So I end up, for now, in the upper left quadrant. All Israel need do is re-embrace the two-state solution, it is not about strong vs. weak.

I'm hardly alone. You can hardly get more mainstream than Biden, Blinken, and Thomas Friedman. Their great sympathy for Israel is vestigial, affection for an Israel that no longer exists. They share my fundamental analysis; only the two-state solution can bring a humane peace.

Noisy campus protesters screaming about settler colonialism and oppression by the powerful is analogous to Michel Foucault in 2001, significant but not the real story. Few people are strongly ideological but the few who are scream really loudly. A better understanding of opinion change among the young is Kevin Drum's

https://jabberwocking.com/seeing-israel-through-young-eyes/

Similarly "progressive" came into wide use after Reagan and later Republicans made "liberal" a dirty word. "Progressive" evoked Teddy Roosevelt and other progressives after the gilded age. It was a self-description that for a time did not turn off voters. Discussion about the meaning of progressivism are like discussions of true conservatism, common usage differs from clean ideological descriptions.

I don't think tying people like Butler to progressivism will work. "Progressive" is now closely tied to Bernie Sanders and AOC and the Squad, all of whom are, in the political science sense, liberals.

I believe you are correct in pointing out that the Butlers of the world are only interested in opposing the "American Empire" and that is why they support insane things. However I still think that thesis does not really save much face for them. They are still insane and, worse, morally bankrupt.

One of the reasons why they can live with that contradiction and still feel good about themselves is that they are insulated from the consequences. You can support Hamas as much as you want from the comfort of your prestigious Western tenured job. That is the morally bankrupt part.

But I would add that insanity is still important. Of course, it does make sense that if that guy really thinks he is Napoleon then he orders the invasion of Russia every week he gets excited, but that does not make him less insane. To believe in the "direction of history" to the point where you side with those who would behead you needs to be considered insane, no matter how much rationalization one includes to explain oneself away from the consequences.