This Is the Fast I Have Chosen

My first Tisha B'Av observance in years felt very different than it used to

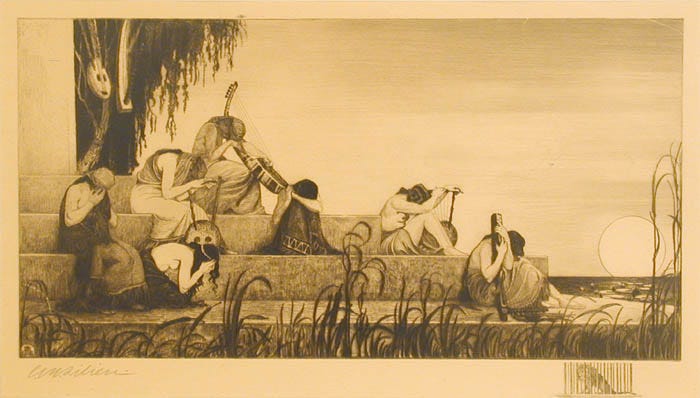

Ephraim Moshe Lilien, On the Rivers of Babylon, 1910

Tuesday was Tisha B’Av, the saddest day on the Jewish calendar, and I observed the fast for the first time in years. It was a very different experience from back when I used to observe. My period of peak religiosity corresponded—mostly by coincidence—with the period of the Second Intifada, when bombs were going off regularly in nightclubs, in restaurants, on buses. Observing Tisha B’Av in that context, I felt a feeling of continuity. Our people suffered then, and cried out; our people were suffering now, and were crying out. It all felt entirely natural, entirely appropriate.

Years later, as I became less religious, Tisha B’Av was one of the observances that fell away. Partly this was just what I called the normal attenuations of liberalism—but in this particular case there was also an ideological edge to my non-observance. The canonical sources disagree over whether the fast of Tisha B’Av was observed in the Second Temple period or not; Rambam says yes, Rashbatz says no, and the Sfas Emes says they only fasted in times of trouble, not in peacetime. So now that Jewish sovereignty had been restored, should we continue to fast? I wasn’t sure, and the more I thought about it the more I thought that answer needed to be “no.” I came to feel that continuing to fast was a refusal to accept good news, and had an edge of “this is not enough” that, while I could accept it in a spiritual sense (of course it’s not enough—the Messiah hasn’t come yet), I positively recoiled from in its primary political valence, which ends in a truly lunatic place.

But this year, in a new time of trouble, I went back. I sat on the floor in the dark, read the book of Lamentations, chanted kinot, and fasted. Our rabbi added a number of post-October 7th poems to the service, and it was striking but unsurprising to me how strongly they resonated with the ancient text. And I realized, as I sat there, that I had misunderstood Tisha B’Av in my previous period of observance.

Tisha B’Av is not primarily a time of crying out for divine assistance in the midst of travail. That’s Passover’s story, one that ends, obviously, with triumph and deliverance. Tisha B’Av’s view comes after the destruction that had no deliverance, after it is too late for God to intervene. Nor is it solely about mourning loss, though it obviously is about that. Most fundamentally, it’s about abandonment.

The last two lines of Lamentations are:

הֲשִׁיבֵ֨נוּ יְהֹוָ֤ה ׀ אֵלֶ֙יךָ֙ (ונשוב) [וְֽנָשׁ֔וּבָה] חַדֵּ֥שׁ יָמֵ֖ינוּ כְּקֶֽדֶם׃

Return us, O LORD, to Yourself,

And we shall return;

Renew our days as of old!כִּ֚י אִם־מָאֹ֣ס מְאַסְתָּ֔נוּ קָצַ֥פְתָּ עָלֵ֖ינוּ עַד־מְאֹֽד׃

For You have rejected us utterly,

Raged against us too fiercely.

When we read Lamentations on Tisha B’Av, the penultimate line is repeated after the final one, so as to end on a note of hope (or pleading for hope), rather than despair. But my point is, that final note is not “save us from our trouble!” but “take us back to you!” Because the trouble has come, and done its worst. Now we are in exile, and by the rivers of Babylon we don’t just weep that Zion is lost, but that God didn’t come when He was called. That’s the wound we need to be salved; we need to be reassured that God is still there, even though He didn’t come when He was called.

That’s why the post-October 7th poetry resonated so powerfully with the text of Lamentations and with the holiday more generally: because the poets were accessing that feeling of abandonment. But while some of them invoked God’s absence, they also invoked another, more mundane absence: of the army, and of the state. That sense of abandonment by those who were supposed to protect them is, I think, the deepest wound of October 7th to the Israeli psyche.

The reason for that lies deep in the heart of the Zionist project. One of the foundational texts of political Zionism is Hayim Nahman Bialik’s poem, “In the City of Slaughter,” about the Kishinev pogrom of 1903 in which dozens of Jews were murdered, including children, Jewish women were raped en masse, and hundreds of homes were burned. Bialik’s poem is a moving lament, but it is also a furious diatribe against what he saw as the abject helplessness of the Jews of Kishinev and of the diaspora more generally, and a cry of rage against the traditional Jewish conviction that God was their only protector. He was issuing a literal call to arms, a very direct demand that Jews make for themselves a new god, one who could actually protect them.

That’s the god that failed on October 7th. Re-reading “In the City of Slaughter,” I found little resonance today, because while the atrocities of October 7th ring with horrible familiarity with Kishinev, the political and social context is totally different. Contra Bialik, the Jews of Kishinev actually did fight back; the men tried to defend their women, they did not hide and watch them being raped as Bialik has them do. They lacked the means of self-defense, not the will or the courage to defend themselves. In 2023, though, the State of Israel had every conceivable means of self-defense at its disposal. And yet October 7th happened anyway.

Lamentations resonated so strongly, I think, because the Jews of the First Temple also had every means of defense at their disposal. They had their own kingdom, and the kingdom of Judah had an army. Jerusalem had its fortifications, and on Mount Moriah stood the Temple with the Ark of the Covenant in it providing miraculous protection. And it was all to no avail: the kingdom was conquered, Jerusalem sacked, the Temple laid to waste, the Ark lost forever.

The restoration of Jewish sovereignty means the restoration of that reality. It’s not the end of history—that will come not on the last day but on the very last—but the return of the kind of history that a sovereign state can engage in. And in that history, things like October 7th can happen. If that means Zionism’s project is a failure, then Judaism’s project is also a failure, and liberalism’s project is a failure, socialism’s project is a failure, Christianity’s and Islam’s projects are failures—in fact, every human project, whether aimed at the divine or not, is a failure. Which is not, I think, a terribly healthy or useful way to evaluate any approach to life, counting it a failure if cannot guarantee success.

At the start of Tisha B’Av, you sit on the ground and wail not because you realize that what you have now isn’t enough—that you need more land, or more prayer, or perhaps more cognitive empathy, to be completely secure—but because you realize that nothing is enough. Even building a house for God to dwell in right in the heart of your capital isn’t enough to ensure against destruction. And so I sat and wailed. I was mourning the dead of October 7th, mourning the destruction that Israel unleashed in response to October 7th, and mourning the possibility that we’re only seeing the beginning of a wave of destruction that could—I don’t believe it will, but I know that it could—end the third Jewish commonwealth.

But by the afternoon of Tisha B’Av, before the fast is even over, you’re supposed to get up off the floor, put on your tallit and your tefillin, and start planning for the day after destruction. For building back, hopefully better, notwithstanding your knowledge that nothing will be enough to ensure what you build either, because the one thing you do know is that this isn’t the very last day. Tu B’Av is right around the corner, in fact; within a week of Tisha B’Av’s lamentation over death is the most auspicious day on which to get engaged, or to get married. Because in the end, that is the only proper response to death: not vengeance and not despair, but more life.

This is great, thank you. Here's a related thought:

There are two passages in the Talmud that provide reasons for the destruction of the second Temple. One, in Tractate Yoma, 9b, says that it was destroyed because it held "Sinat Hinam" often translated as baseless hatred. The other, in Gittin 55b, tells a story of a host who accidentally invites his enemy, Bar Kamsa, to a party, when he intended to invite his friend, the similarly named Kamsa. The host humiliates Bar Kamsa at the party, who initiates a revenge plot that involves having the Roman governor send an animal to the Temple to be sacrifice which is not technically fit for sacrifice by Jewish law. At the advice of Rabbi Zecharia Ben Avokolos, the sacrifice is not given, as that would be improper, nor is Bar Kamsa executed, which would show the Romans that they had been played, as he has not technically committed a crime worthy of the death penalty. The Romans take this as a sign of rebellion, and thus beings the opression that lead to the first Jewish Revolt, and ultimately the destruction of the Temple. As a later gloss on the story, R. Yochanan says that it is the humility of R. Zecharia ben Avokolos that caused the destruction of the Temple.

Notably, the story of Kamsa and bar Kamsa doesn't mention baseless hatred at all. Nevertheless, most people understand the comment about baseless hatred in Yoma to be referring to the enmity between Bar Kamsa and the host in this story. However, I think it's saying something very different.

R. Zecharia ben Avokolos's humility is the idea that somehow Judea can escape the notice of empire, that it can get by without engaging in politics. His naïve understanding of religious law without a thought to the wider world, to the very real power dynamics at play, which is important context for making a decision about how to act. Whether there is a Jewish state or not, Jews live in the world, act in political contexts, and refusing to recognize or acknowledge them, to withdraw to a context-less understanding of halakha.