The Meaning of Zionism in a Post-Zionist Era

A meditation on the occasion of Israel's 75th birthday, and the 45th anniversary of the completion of the Zionist project

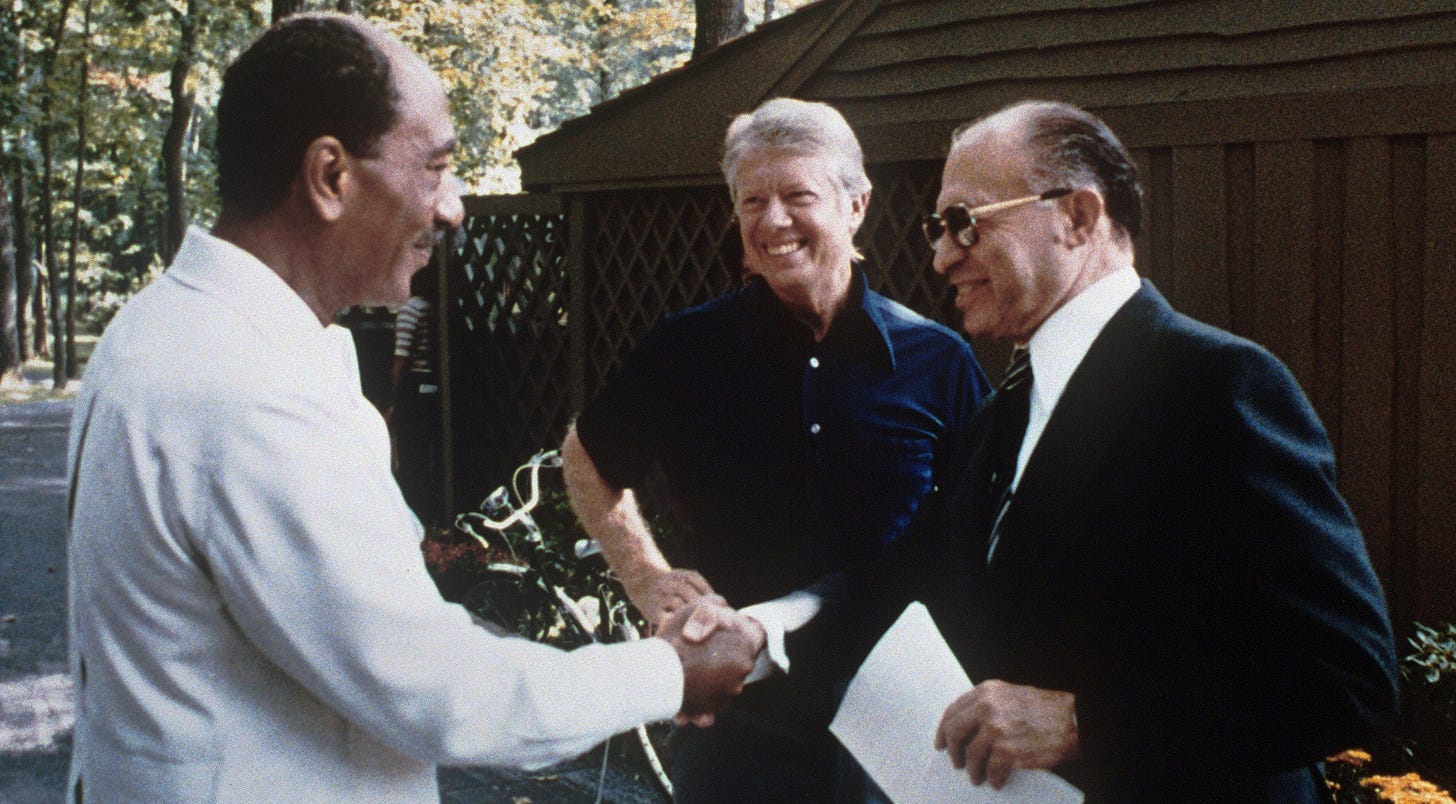

Menachem Begin, Jimmy Carter and Anwar Sadat at Camp David, 1978

There’s this conversation I’ve had multiple times with people of different ages where I endeavor to understand their world outlook in terms of their foundational political memories. For Americans, I tend to think that whoever was president during the years that you first become aware of politics as a thing, that’s who, on some level, you’ll always imagine is president. If your world was transformed by war at a crucial age, or by some other political earthquake, that will shape how you see the world forever after—not in a simple, linear way, but in ways that can be readily discerned.

I was born in 1970. Reagan, on some level, will always be president for me, not in the sense that I share Reagan’s political views or that I expect the current president to do so, but in terms of his persona. I’m sure that has something to do with why I so deeply disliked President Clinton, who was so profoundly different from Reagan, and why I so readily liked both President Obama and President Biden, who were more like Reagan in crucial ways (the former for making great speeches and having a kind of warmly regal dignity, the latter for having a fundamentally sunny disposition and, honestly, just for being a charming old Irish guy). The major political earthquake at a formative moment that deeply shaped my understanding of the world was the fall of the Berlin Wall, which felt like it confirmed at a deep level Reagan’s outlook on the world. That continues to shape me, even when I reject aspects of that outlook. I don’t think it’s an accident that embraced so much of the neoconservative understanding of the 9-11 attacks at the time, because doing so was just reacting to a new earthquake through the lens of the previous one. I think someone born ten years later, who never really experienced the Cold War, for whom Clinton will always be president and 9-11 and the Iraq War were the formative earthquake, would come to understand the world, intuitively, in a very different way.

My first political memory, though, was of the Camp David Accords. I grew up in a deeply Jewishly though not particularly observant household, and both my mother and father were Zionists, my father fiercely so. I was too young at the time to have much context for the event, but I can still remember the profound feeling from the time that this was what “events” in the world looked like. I also remember feeling that it was personal, that for the President of Egypt to make peace with Israel was, on some level, what the Zionism I had been raised in was all about. Political Zionism, after all, was a call for the radical transformation of the condition of the Jewish people, from an anomaly to something more “normal” among the nations of the world—a people with sovereignty in their homeland and an equal standing with other nations of the world.

That ambition was fulfilled, if not in 1948 then certainly in 1978. When Egypt, the largest and most important Arab state, the leader of the Arab Nationalist cause and Israel’s most powerful enemy, made peace with the Jewish State and acknowledged its sovereignty, Zionism’s fundamental goal was achieved. In the wake of that event, Zionism could no longer mean what it had meant before. It could no longer mean the establishment of a Jewish state—the state existed, and was not only accepted by the world powers but by the key rejectionist power in the region. To be a Zionist after 1978 meant using that word to mean something different.

Of course, there are other Zionisms than the political Zionism I’m talking about—the cultural Zionism of Ahad Ha’am, the religious Zionism of Rav Kook, and so forth. Any number of projects that could be called “Zionist” can still be counted as incomplete. And I don’t want to suggest that Zionism was in any sense rootless, that political Zionism always aimed at creating Theodore Herzl’s secular, blonde-haired, German-speaking utopia. Zionism has always had a religious dimension; the Israeli flag is based on the Jewish prayer shawl, and the Hebrew language, which Zionism brought back to life, is deeply inflected with religious meanings, unavoidably so. But that is because the Jewish people themselves from the beginning had a religious foundation, not because political Zionism itself was ever intended to be something other than a political movement. I maintain that after 1978 at the latest, that movement was no longer a coherent living ideology, but a fact of history. And while I was too young to understand that at the time, I think my outlook on the world, as a Jew, has been profoundly shaped by growing up in an objectively post-Zionist era, just as the outlook of someone who never knew the Cold War would be profoundly different from the outlook of someone who grew up in its shadow.

My relationship to Israel, for example, is fundamentally a familial one rather than an ideological one. I care deeply about what happens there, and am invested in its politics, but not as a cause or a project that I conceive myself as laboring for. Rather, I’m invested because Israel is family. If Israel goes fascist, that’s a part of my family going fascist, and it pains me. If Israel suffers from a spate terrorist attacks, or a war, or a natural disaster, that’s part of my family going through that suffering, and it pains me in a different way. Israel also matters to me because, for all that I am not nearly as observant as I once had planned to be (I roll on shabbos and would totally eat at an In-N-Out Burger), when Israel behaves inhumanely or, for that matter, un-Jewishly as I understand it, it does so in the name of the Jewish people, by its very nature. But I know where I live. New York is my home; America is my country; my life is here. If I decided to pull up stakes and move to Israel, yes there’s a sense in which I’d be “coming home,” but another sense in which I would be leaving home, and not just because New York is familiar. I really do know where I live, and I don’t believe there’s anything wrong with my living where I live, that I am in any sense out of place or incomplete here.

That’s one reason I don’t tend to call myself a Zionist. To be a Zionist, in a post-Zionist era, is like being any other kind of nationalist after independence has been achieved. It’s a change of focus, from the existence of the state to its character, from its relationship to an imperial power to its relationship to its neighbors and, especially, to its own citizens, particularly its citizens that are members of ethnic minorities. The Arab Nationalist government of Egypt expelled the Egyptian Jewish community, a community that had existed in the country since before Roman times, because they considered them alien to the Egyptian nation. That was a perfectly ordinary—if terrible—thing for a nationalist movement to do. I wouldn’t expect Jewish nationalism, in a post-independence context, to be any different in principle.

Israel has been struggling, for decades, to sustain a liberal Zionism because in a post-Zionist era, where Zionism’s key goals of statehood and recognition have been achieved, Zionism is just nationalism and nationalism is an inherently illiberal ideology. Seeing that illiberalism on full display in the current government has finally started to open the eyes of numerous self-identified liberal Zionists in Israel—particularly right-wing ones—to this reality, even if they likely wouldn’t put it in those terms.

I want to be clear what I am saying. I’m not saying that Zionism—Jewish nationalism—is illegitimate in a post-Zionist era, where statehood and recognition have been achieved. I’m just saying that it means something different. It means the same thing that Hungarian nationalism or German nationalism or French nationalism means. I’ve been arguing for years that the European ambition to keep explicit nationalism out of politics is doomed to failure and only makes the explicitly nationalist parties more dangerous because they become the vehicles for dissatisfaction with the political system itself. But even if nationalism is accepted as a normal part of politics, we should recognize it for what it is: an inherently illiberal force with which liberal forces sometimes have to compromise and sometimes have to fight.

But this, again, is fundamentally their fight, a fight for Israelis, not for American Jews who would like Israel to stand for a liberal Zionism that they can pleasantly affirm. They live there. I live here, where I grew up, where I call home. Saying that does not in any way sever the ties that bind me to Israel any more than the boundaries that exist—and should exist—between me and any other member of my family somehow sever me from them. It’s just a reminder that those boundaries exist.

I haven’t celebrated Israel’s 75th birthday in any explicit way, but that’s not an anti-Zionist statement on my part. (Anti-Zionism makes even less sense in a post-Zionist era than Zionism does.) The founding of the State of Israel was an extraordinary event in the Jewish people’s history; it fully deserves to be celebrated by the singing of Hallel, just as the destruction of the First Jerusalem Temple by the Babylonians, and the Second by the Romans, fully deserve to be mourned by fasting and the chanting of Lamentations. But I don’t observe Tisha B’Av every year either. These are the normal attenuations of liberalism. On Israel’s 75th birthday, I kind of feel like those attenuations are themselves part of the normalcy that those original political Zionists were striving for.

Your “normal attenuations of liberalism” is a very nice piece of writing, saying so much with so little. Brilliant craftwork!

I wish I could share this with my Conservative shul’s leadership and have them (1) be able to digest this and (2) give a damn.