Thinking About the Future on October 7th

Is the region doomed to another year of ever-escalating war? Or is there an opportunity for peace?

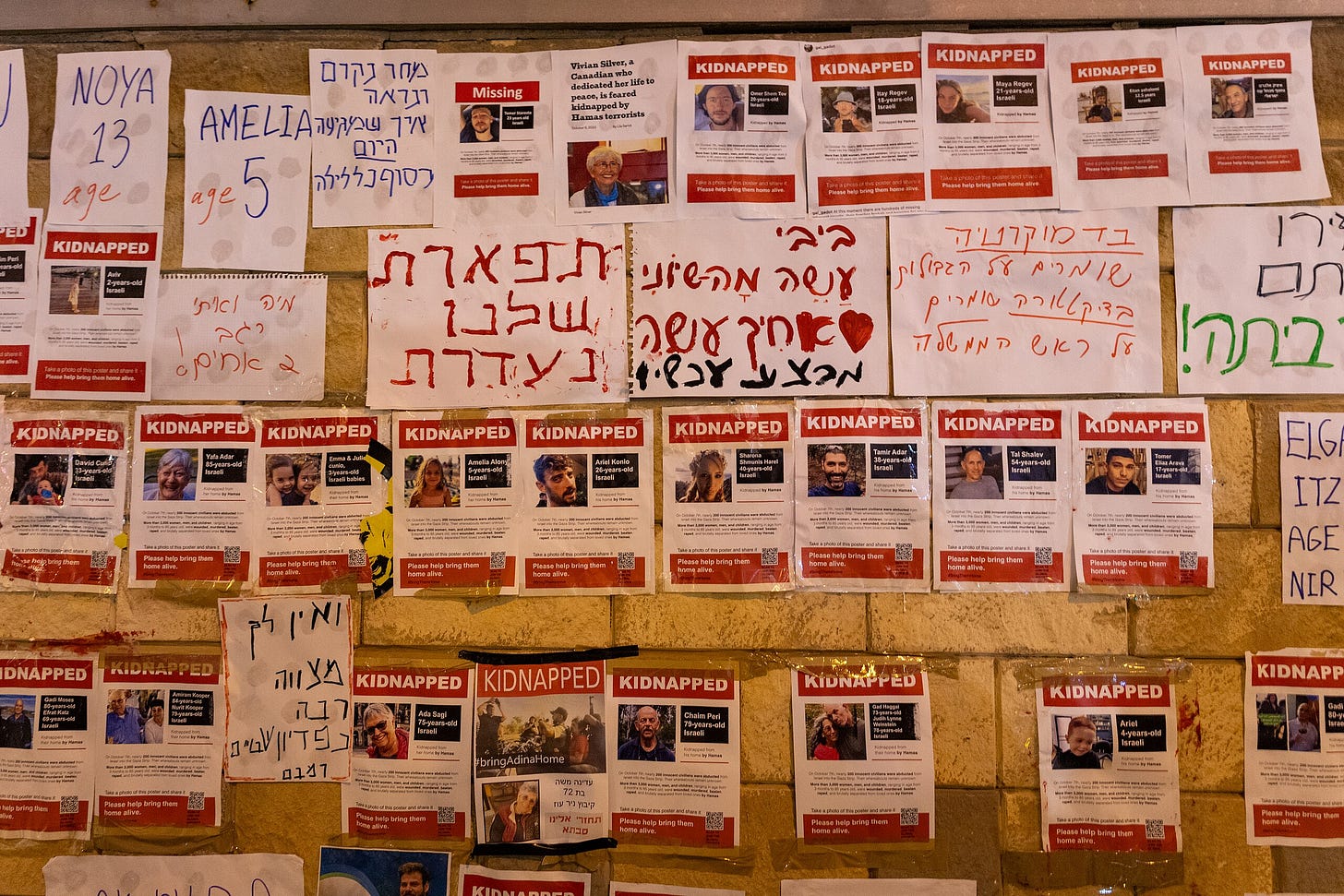

Photo by Oren Rozen

Today is, of course, the one year anniversary of Hamas’s attack on Israel, their massacre of hundreds of innocent Israelis and the kidnapping of hundreds of others, and the beginning of the war that Israel has pursued since then, a war which continues to expand. The yahrzeit for those murdered on October 7th, 2023 won’t be for a couple of weeks yet, but it will always fall on Shemini Atzeret (which is also Simchat Torah in Israel) and in a Jewish context that holiday must take precedence over collective mourning. I did my own mourning on Tisha B’Av, and wrote about it here. Today, on the secular anniversary, instead of mourning the past, I’m going to think about the future.

From one perspective, the future is arguably looking better than it has for much of the past year. The case for thinking positively looks something like this. While Israel’s war on Hamas has failed to achieve true victory (Hamas is weakened but still operational, many of the hostages are still in captivity if they are still alive), the expansion of the war to include Lebanon and now Iran itself has dealt a serious blow to far a more dangerous enemy and put Israel’s most important antagonist on notice that things could get worse still if it does not begin to play a constructive role. No, the abandoned communities in Israel’s north have not gone back to normal, and Hezbollah is certainly not eliminated as a threat. Nonetheless, I’m genuinely impressed by the degree to which Israel had penetrated Hezbollah’s organization and the scope of damage it was able to inflict before even engaging in a ground offensive. I’m equally impressed by Israel’s ability to strike Iran directly, and, in conjunction with their allies (preeminently America) to neutralize a barrage of Iranian ballistic missiles. For the first time since last October 7th, Israel appears to have the initiative, and to be shaping the environment to its advantage rather than just inflicting misery.

This shift in the tactical situation could be a strategic opportunity as well, one that could, if seized, redound to the benefit of the Palestinians as well as Israelis. Iran clearly does not want an all-out war with Israel, one that would very likely involve the United States. It also clearly doesn’t want to cede the assets it has developed in Lebanon, in Yemen, in Syria and in Iraq, nor can it easily afford to show itself as having been cowed by Israel. But it can’t get everything it wants without risking what it wants least. It gained nothing from firing missiles at Israel except the ability to say that it hadn’t meekly accepted Israeli blows; now Israel will undoubtedly escalate further to establish, similarly, that you cannot fire missiles at it with impunity, and what will Iran do then? This road leads to the full-scale war that Iran wants to avoid, and that in turn suggests that there should be an opportunity for a third party to present an alternative path that avoids all-out war while also enhancing Israeli security—something that would involve Iran explicitly not only in a cease-fire but in actual peacemaking.

How can I suggest that there are opportunities for peace now of all times, when, whatever Israel’s tactical successes, the chance of a truly catastrophic wider war never looked higher? I’ll make an analogy. At the start of the Yom Kippur War, Israel was surprised and thrown onto its back foot. There was a genuine fear that the country could lose, even be overrun. In part thanks to President Richard Nixon’s timely assistance, in part thanks to Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s decision not to press his army’s initial advantage, and of course in part thanks to the efforts of the IDF, Israel regained the initiative, retaking the Golan Heights and crossing the Suez Canal to trap the Egyptian Third Army. Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev then rescued the Egyptians through diplomatic pressure, and the war came to an end. This end game taught both sides a lesson: both the Egyptians (who even before the war had already decided that they wanted to make some kind of deal with Israel to get the Sinai back) and the Israelis understood that their maximal objectives could not be achieved by military means. As a result, the ultimate result of that war was the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt.

I very much doubt Iran would take such a path under any reasonably imaginable circumstances—Masoud Pezeshkian is not Sadat and doesn’t have Sadat’s power even if he had his inclinations. But diplomacy has to be tried to find out if an opportunity is there—and can bring benefits even if it fails. For example, even if regime change in Iran is ultimately necessary for the country to be reintegrated into the region, it’s important to remember that a key basis of the regime’s legitimacy is the outside world’s hostility. Hezbollah is supposed to be a forward defense for Iran; if Iran instead gets dragged into a war with Israel in order to save Hezbollah, that will undermine the regime further with an Iranian people that is already fed up. That would be even more true if the regime were also rejecting serious diplomatic overtures at the same time. And it goes without saying as well that the hands of those opposed to Iran within the Arab world—in the Gulf, in Lebanon and among the Palestinians most importantly—would be greatly strengthened by Iran isolating itself rather than successfully isolating Israel while dividing the Arab world. War is not an alternative to politics, but “the continuation of political intercourse with the addition of other means,” and whether we’re talking about Gaza or Lebanon or Iran the path the war has taken presents political possibilities that need to be seized or the gains of war will be wasted.

The problem is that even if a diplomatic opportunity does exist—or if it does not exist, but Israel could benefit from a clear demonstration of that fact—it is vanishingly unlikely that anyone in Israel would consider pursuing it, and equally unlikely that any third party would engage to present it.

To take the second point first, the reason no third party would engage to find such an opportunity is that no third party exists with that kind of breadth of vision. The United States is not a third party; we are Israel’s ally and Iran’s avowed enemy. The European Union is not a credible power of any kind. Russia and China are mostly not interested in playing this kind of role in world affairs, even though it would mean a further demonstration that the world had moved beyond American leadership, and neither is India—the major power best positioned to play this kind of role given its good relationships with both Russia and the United States, and with both Iran and Israel. And third parties with credibility and the ability to deliver benefits to all sides are frequently essential to such peacemaking.

Israel, meanwhile, is trending further away from any serious consideration of diplomacy. That’s been clear for some time on the Gaza front; neither Yahya Sinwar of Hamas nor Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu have shown any serious interest in a cease fire deal that would bring the hostages home. That’s because Sinwar knows the hostages are his only real asset, and he doesn’t care how much the people of Gaza suffer so long as Hamas is still operational, while Netanyahu knows his government will collapse if he ends the war with Hamas still a functioning organization. More broadly though, Netanyahu’s aversion to diplomacy was clear even before the current war, in his approach to the Abraham Accords and the possibility of normalization with Saudi Arabia (for which he was not willing to provide even a diplomatic fig leaf on the Palestinian issue), and before that in his ferocious opposition to the nuclear deal with Iran. Netanyahu has never conducted a diplomatic negotiation in the spirit of give and take; he will do deals that only involve benefits, but is otherwise happy to wait and let problems fester.

The terrible risk of this approach should have become obvious last October 7th. But the practical political consequence of Israel’s so-far successful prosecution of the war in the north has been to salvage Netanyahu’s fortunes and vindicate a purely military-focused approach. Already, the right-wing dissident party of Gideon Saar has agreed to join the government; already, the first polls have appeared showing the government winning a majority of seats if the election were held today. More telling, I think, is the fact that the strongest potential candidate to succeed Netanyahu is not the centrist Yair Lapid, nor the left-wing Yair Golan, nor even the center-right Benny Gantz—who once looked like the Prime Minister in waiting but who now loses in head-to-head polling contests with Netanyahu and whose party has faded dramatically in the polls—but the far-right Naftali Bennett who was briefly prime minister of Israel’s thirty-sixth government. Bennett is not comparable to extremists like Itamar Ben Gvir or Betzalel Smotrich who have wielded so much power in the current government; he’s a serious leader not a thug or a fascist. But his views are unequivocally far-right; he has historically advocated Israeli annexation of the West Bank, for example. That’s the direction Israel is going, and it is not a road that leads to peace.

I still find the idea of Bennett’s accession more hopeful than the idea of Netanyahu winning another mandate. I find Bennett’s vision delusional in many ways, but at least he is a man of vision, and I can imagine him surprising me, as Netanyahu never will. Nonetheless, I cannot feel terribly optimistic. Despite what I see as a strategic opening created by tactical successes, I think the relevant parties—both Israel and its enemies—won’t miss an opportunity to miss an opportunity.

I don’t believe that that’s the legacy that anyone who was murdered or kidnapped last October 7th would have wanted, nor those killed in the wars that have followed. But the choice of how best to honor them is up to the living.

Israel will work to prevent any improvement in US-Iran relations, as I read this.

"Opportunity for peace"!? Sounds extremely unlikely I'm afraid! As you say, there is seemingly NO "third party" to facilitate such an agreement. PLUS you think if Netanyahu left office, NAFTALI BENNETT would be his likely replacement!! OY VEY what a truly unholy mess!