The World Only Spins Forward: Anti-Zionism Edition

Opposing something that has already happened is a literally nonsensical position

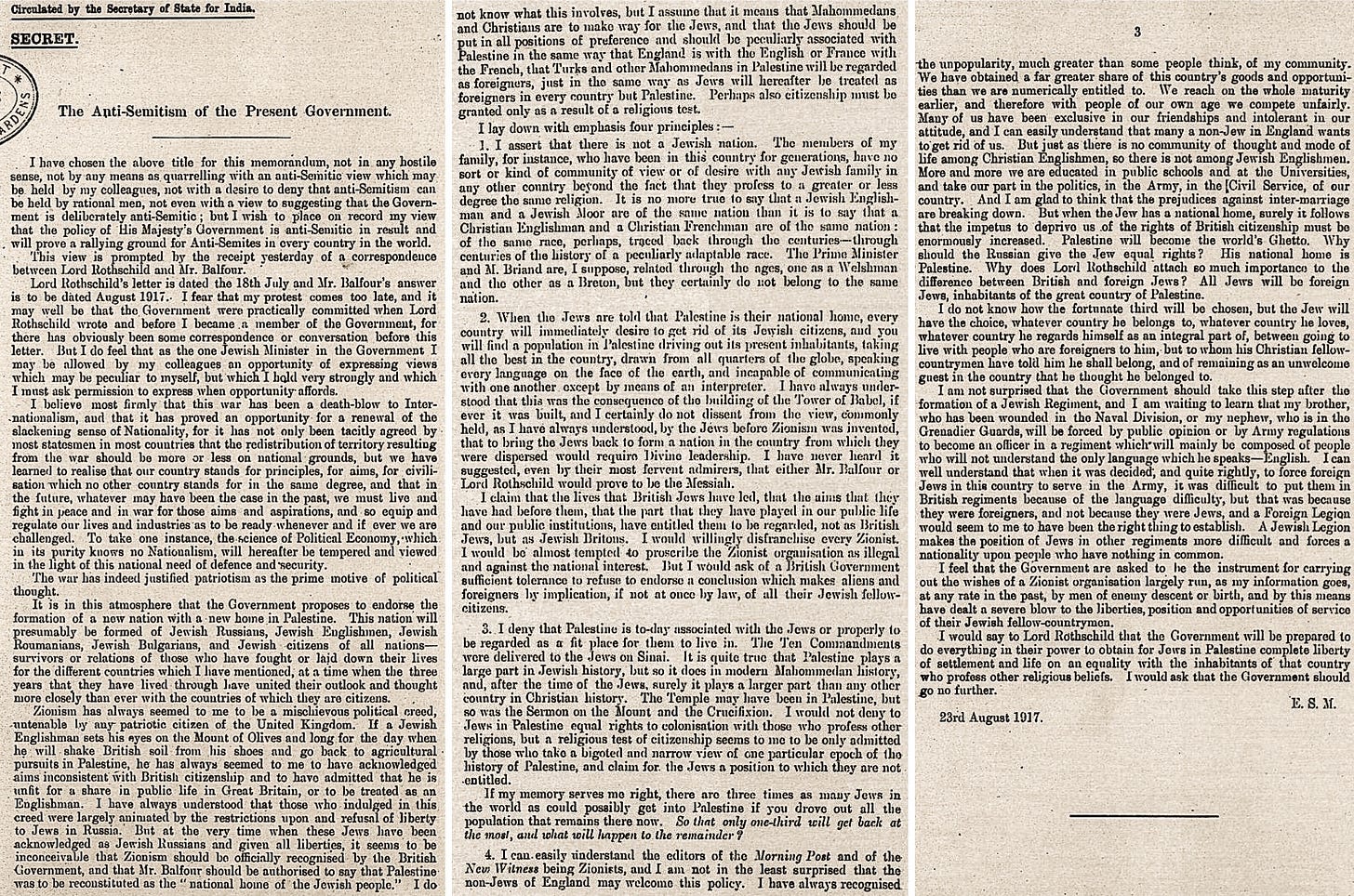

Letter from Edwin Samuel Montagu, British Secretary of State for India and a practicing Jew, attacking as antisemitic the Balfour Declaration calling for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, which had just been issued by his own government.

In a post I wrote not long ago, I argued the we live in an objectively post-Zionist age. The essential objective of political Zionism—the founding of a Jewish state—had been accomplished, and therefore the ideology was obsolete. Therefore, if people continued to profess to be “Zionists,” the word must mean something different—related, no doubt, to one or more varieties of pre-state Zionism, but clearly distinct from it as well.

In a post-Zionist age, you could still have religious Zionism, and believe that the founding of the state was the first step toward the arrival of the messianic age. You could still have cultural Zionism, and believe that Jews the world over should center their Jewish identities on the transformation effected by the restoration of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel. You could still believe that Jews are not truly “whole” unless and until they move to Israel, that the State of Israel should facilitate Jewish settlement of the entire historic Land of Israel, that it should nurture a Jewish national consciousness in the country and in the diaspora, etc. You could hold to any number of nationalist, religious or other ideologies that are tributaries of the Zionist stream.

But you could also have been a pre-state Zionist and have rejected any and all of these premises. What you couldn’t reject was the idea of the restoration of Jewish sovereignty, because that was central to the Zionist project. And that central objective has been accomplished. Therefore, we live in a post-Zionist age, and “Zionism” doesn’t mean what it once did.

Very few Jews that I know are rigorous about this when they use the term, and my usage differs from the way most Jews of my acquaintance talk. (That, in fact, was the reason I wrote the post.) Most of my friends from synagogue, for example, have affection for Israel, are glad that there is a state that represents the national aspirations of the Jewish people—and a place that they could flee to if the worst were to come to pass where they live—and even see the founding of the state as a kind of modern miracle. To my mind, that package doesn’t add up to “Zionism” as a coherent ideology. But most of them would call themselves “Zionists” while I—who share those sentiments—am inclined not to call myself that. I don’t want to call myself a Zionist unless it’s clear what that means, and I don’t think it is clear. So I prefer to describe my own feelings and relationship toward Israel—the state that actually exists—without explicitly affiliating with an ideology.

In a parenthetical aside in that same post, however, I also said that “anti-Zionism makes even less sense in a post-Zionist era than Zionism does.” I thought that aside deserved to be expanded, and that’s what I’m going to do here. Why do I think anti-Zionism makes no sense in a post-Zionist era?

The simplest answer is in the title of this post: the world only spins forward. If political Zionism was an ideology that called for the founding of a Jewish state, anti-Zionism was a stance that opposed that ideology and its goals—that thought a Jewish state should not be founded. In the most basic sense, this is an obsolete program. The Jewish state was founded. It exists. Opposing something that has already happened is a literally nonsensical position.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that you can’t decry something that has already happened. You could, for example, believe that the partition of Ireland was a mistake, even take the position that this mistake should be reversed. The IRA took that view, and conducted a campaign of terrorism for years aimed at compelling Britain to abandon Ulster and at uniting the six counties thereof with the Irish Republic by force. But this is not at all the same thing as opposing partition before it happened. Similarly, Russia right now is fighting a war to reverse what it views as the mistake it made in 1991 in recognizing the independence of Ukraine. That is a very different action from having demanded an adjustment of borders back in 1991 as the price of recognition, or from having refused to dissolve the Soviet Union in the first place. You can change course as you go forward, in other words, but you can never go back.

Much of the rhetoric of anti-Zionism, though, presumes that you can. Does the fact that Israel exists mean that it’s “literally nonsensical” to try to dismantle it? No, of course not—but it should be clear what you are advocating if that is your stance. If you are a Palestinian nationalist, for example, that just means you favor a sovereign state for the Palestinian people. Depending on your conception of that state, there might or might not be a place for minority populations in it, and the relationship of such a state to its neighbors might similarly be more or less conflicted—those questions are open to a variety of answers all consistent with a demand that the Palestinian people get a state of their own (which is the indispensable demand of Palestinian nationalism). There are versions of this demand, in other words, which would not require endorsing Zionism—they would be “non-Zionist” because they would not spring from Zionist ideological premises—but that would not be “anti-Zionist” in the sense of requiring the wholesale undoing of what Zionism accomplished: the creation of the State of Israel.

Other versions, though, might require just that. A Palestinian nationalist who specifically favored a Palestinian state “between the river and the sea,” for example, quite obviously favors the destruction of Israel. Even there, though, there’s some ambiguity. Is the idea that there should be a unitary bi-national state? That there should be a unitary Palestinian state with a tolerated Jewish minority? Or that the Jewish population should be expelled or killed? Calling the maximalist Palestinian nationalist position “anti-Zionist” obfuscates this question by focusing on the past, on what happened in 1947. But the question isn’t what you wish had happened in 1947, but what you want to happen, and are trying to make happen now, in 2023. This obfuscation is strategic, of course, but it should be obvious why Israelis reasonably interpret it in the most threatening ways, which guarantees wall-to-wall opposition among any Israelis who care at all about their country, as well as any well-wishers abroad.

So there’s a strategic argument for not using the term unless you really are a maximalist and want to advertise that fact in order to maximize the scope of conflict. But the term presents problems for internal reasons as well: because it defines your objectives negatively. You’re not arguing about what you want to build; you’re focusing on what you want to tear down. But this only makes the enemy psychically stronger within the soul of the person who holds such a focus. This can have some particularly ugly ramifications in practice. I’ve heard multiple people who call themselves anti-Zionist say things like that Jews aren’t really a people because they are a religious group, or aren’t “really” descended from the people who lived in the Land of Israel in Roman times, or otherwise don’t fit their template of the “correct” way for a people to be. If you want to understand how “anti-Zionism” can become antisemitism, that’s as good an explanation how as any, in my opinion. And that danger is reason enough to at least be wary of embracing “anti-Zionism” as opposed to “non-Zionism” as a stance.

What if you are a Palestinian Israeli (that’s both a neutral term and the term generally preferred by the people in question, which is why I use it)? Doesn’t Zionism inherently condemn you to the status of a second-class citizen? So wouldn’t you be anti-Zionist by definition? A Palestinian Israeli Zionist is certainly going to be an unlikely combination. Nonetheless, if you were a Palestinian Israeli who was not a Zionist, you could still hold a variety of views. Maybe you accept Israel’s status as a Jewish state without endorsing it, and focus on rooting out discrimination against non-Jews (and there is a lot of discrimination in Israel against non-Jews, and against Palestinian Israelis in particular, notwithstanding the fact that Palestinian Israelis are citizens with full voting rights and a robust presence in Israel’s society and economy). Maybe you think Israel should be transformed into a bi-national state, or a “state of all its citizens” (whatever that means; I’m never quite sure). Maybe you want overwhelmingly Palestinian areas within Israel to have the status of national minority territories with some control over who lives there (meaning: the right to preserve their Palestinian character, where currently Israel considers it a state interest to actively break up such areas by building new Jewish communities). There’s quite a bit of viewpoint diversity among Palestinian Israelis, and the foregoing list isn’t intended to be exhaustive.

What unites these diverse views, though, is that they are “non-Zionist” because they are all conceptions of the state that don’t spring from Zionist premises. Are they “anti-Zionist” though? I’m not sure how to answer that definitively because I don’t know what the boundaries are for being a Zionist now that the central Zionist project has been accomplished. I can’t see how fighting discrimination against non-Jews or fighting for their advancement within Israeli society is anti-Zionist. National minority status for overwhelmingly Palestinian areas would seem to be an even easier lift; Avigdor Liberman of the “Israel Is Our Home” party has advocated transferring the Triangle region to the Palestinian Authority and stripping its inhabitants of Israeli citizenship. That’s a blatant violation of international law and vehemently opposed by the Palestinian Israelis who live there—but might there be some version of autonomy that could win the support of both Lieberman and the Palestinians who live in the Triangle region? Who knows? Bi-nationalism is surely a bridge too far though, right? Well there were Zionists in the pre-state period who were bi-nationalists; who’s to say whether we might have them again in the future? Heck, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, founder of right-wing Revisionist Zionism, called for equality between Arabs and Jews in the new state, equality between Hebrew and Arabic as official languages, and equality of representation within the government.

Once again, then, defining oneself as “anti-Zionist” isn’t required in order to have political views that would mean dramatic changes to Israel’s relationship with its non-Jewish citizens, and its Palestinian citizens specifically. There are a variety of non-Zionist ideological perspectives to ground those changes that might win the support of people who call themselves Zionists (whatever they mean by that). If your goal is to make those changes happen, that ought to matter to you.

I’ve been focused on Palestinians because they are the stateless people at the heart of the matter, the ones who have the greatest stake in the question. The same points, though, apply to anyone who isn’t Palestinian but has been drawn, for whatever reason, to the Palestinian cause. But what about diaspora Jews? Isn’t “anti-Zionist” a useful term for them to use, to distinguish themselves from their neighbors (or elders) who profess to be Zionists, to make clear that they not only don’t like what Israel is doing but that they renounce the implicit connection, even obligation, to Israel that Zionist ideology claims they have? They would seem to have the strongest basis for using the term of anyone, right?

I don’t think so, actually. There are the same problems with the term that I’ve already mentioned above: it ignores the fact that it’s not 1947, and Israel actually exists; it centers on what you oppose rather than what you favor, thereby giving what you oppose greater power over you; it presumes to know what Zionism is (which is no longer fixed or clear) and implicitly erases the vast range of non-Zionist points of view that people who think of themselves as Zionists (whatever they mean by that) might be able to agree with; etc. But the term has another problem that I think is only really relevant to them—to us.

There was an expression that I heard a lot during the run-up to the Iraq War: “not in my name.” I felt, at the time, that this was a narcissistic slogan, an implicit rejection of the implications of common citizenship. If you were American, the Iraq War was being waged in your name, like it or not, and chanting otherwise didn’t change that fact. So too with Israel today, in its actions and in its identity. Israel claims to be a Jewish state. That emotionally implicates Jews whether they feel a connection to that claim or not. And I think the embrace of the anti-Zionist label is a misguided response to that sense of implication.

I want to be correctly understood. I’m not saying in any way that antisemitism is justified by Israel’s actions, much less by Israel’s existence. God forbid. I’m not even saying that antisemitism is understandable even though it is unjustified. It’s predictable that anti-Israel agitation—including totally legitimate action that isn’t antisemitic in nature—will attract antisemites to its banner, but that’s as far as my “understanding” extends; beyond that, I think, you really are starting to make excuses for the inexcusable. No, I’m saying that you can’t escape being implicated, internally, by what your fellows do, and that if you’re Jewish, and at all self-aware, that applies to Israel’s actions.

I know that’s how I feel. Israel’s current government has elements in it that I think are reasonably described as fascist. The prime minister is a man who has no honor and has brought his country to catastrophe. There is a slow-motion process of ethnic cleansing taking place on the West Bank, and a brutal war with a horrific civilian death toll being fought in the Gaza Strip. The fact that Hamas is a terrorist group with a genocidal ideology that just two months ago perpetrated the worst massacre of Jews since the Holocaust and is fighting in ways that tend to maximize Palestinian casualties—or the fact that the PLO made the fatefully disastrous decision to walk away from the table when Israel made its most serious peace proposals based on a two-state solution in 2000-2001—those facts are true, and they are exceedingly relevant. But they don’t erase the facts about what Israel itself is doing. Indeed, even if I accept Israel’s justifications for its actions (as I sometimes do), that doesn’t erase the actions or their consequences. More than one thing can be true at once, and all of it implicates me whether I call myself a Zionist or not, simply because I am a Jew and Israel is a Jewish state. It implicates me to myself, regardless of whether anybody attacks me for it—and, again, attacking me for it would be completely illegitimate. It implicates me because that’s what being part of an identity group of any kind means.

It doesn’t implicate me with guilt, mind you. It’s flatly antisemitic to say that Jews everywhere bear the guilt of Israel’s actions, or of its existence. I think people often feel it as guilt, and that part of the motivation for calling oneself “anti-Zionist” may be to deflect that guilt, to win absolution by saying that you’re not one of “those” Jews. But the actual issue here isn’t guilt, and the narcissistic quest to escape it into a state of innocence. The actual issue—the actual feeling—is shame.

I understand why someone Jewish would feel shame when the self-proclaimed Jewish state commits crimes. I feel it myself. That’s the flip side of feeling pride at Israel’s accomplishments; you really can’t have one without the other. But I don’t think that shame can be deflected, certainly not by disclaiming fellowship.

So Jews should feel free to declare themselves not to be Zionists—to favor radical change in Israel or to have no strong opinions about Israel at all. But the ties that bind us are mostly not chosen by us, and often cannot really be escaped, only wrestled with. That’s something the early Zionists understood, and it shaped their worldview fundamentally. If agreeing with them in that is enough to make me a Zionist, then maybe I am one after all. But if it is, then in a sense, maybe I think we all are.

Noah, I don't know if anyone else is confused by the term "Zionist". It is accepted by friends and foes of Israel alike, in its meaning as one who supports the idea of the Zionist ideology, an idea that now includes the fact of the State of Israel. If you believe that the dream of a national home for the Jewish people has been realized in the State of Israel, and you support that, then you are a Zionist, whether you agree with everything Israel does or not. I think I understand what you are getting at--that there are more colors in the rainbow than can be painted by the terms "Zionist" and "anti-Zionist." One refusing to be pigeonholed can simply add a clause when defining him or herself for others. For example: "I am a Zionist but I believe that the Palestinians should have a state of their own." Or: I am an anti-Zionist but I believe that the Jews should be able to live, somewhere (Alaska?), in peace." More tortured souls can add more clauses. Isn't this how the problem you are describing handled today?

There is a history of lost national causes waiting to be written, one that would both draw parallels between the bitter, fabulistic, often bigoted psychology of their adherents and explore how their trajectories differ according to historical and cultural circumstances. Anti-Zionist Palestinian nationalism would be one case study here, the Confederate Lost Cause mythology another, and Biafran nationalism another (if only to illustrate that these causes can be quite sympathetic). Maybe throw in the cult of Bonnie Prince Charlie, too. Whether the IRA or Sinn Fein should be included is an interesting question, given that these days their lost cause of a united Ireland is looking a bit less lost due to remarkable demographic and economic transformations.

This is of course also what gives Chabon's _The Yiddish Policemen's Union_ much of it's power: the exploration of what Zionism would look like as a lost cause.