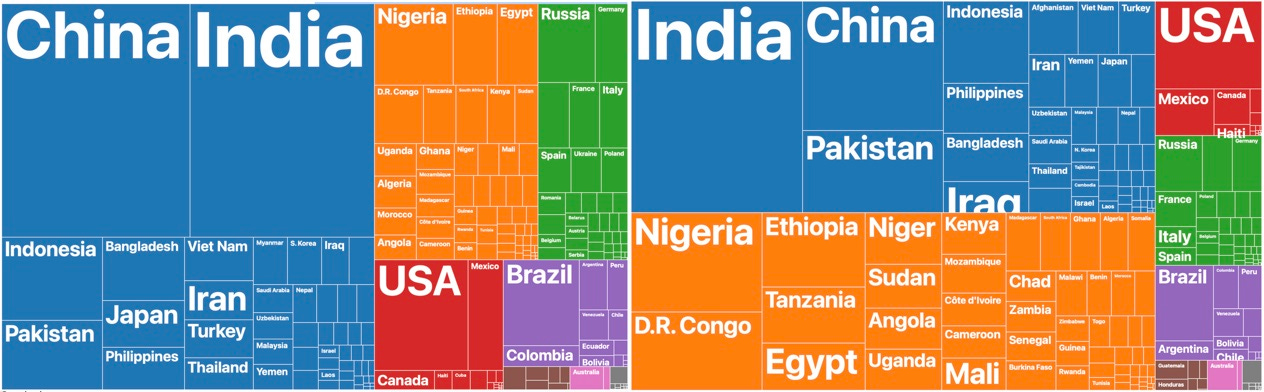

The world in 2020 versus the world in 2100. From PopulationPyramid.net.

The New York Times had a wonderful graphic-centered piece earlier this week illustrating the dramatic demographic transition happening across the world. None of the facts the piece describes should be new to anyone paying attention: Europe is getting older; East Asia, though not as old as Europe yet, is getting older even faster; South and Southeast Asia are entering a zone of prime “demographic dividend” that helped power East Asia’s rise; and essentially all the projected demographic growth of the latter part of this century will take place in Africa, while the rest of the world shrinks. (Africa is undergoing a similar demographic transition to the rest of the world but with a significant lag.) Nonetheless, it’s still striking to see it all graphically depicted in one place.

The primary frame of the Times piece is aging and how different societies are going to handle it. We’ve never seen a society with 40% elderly people; what will one look like? Around 30% of Japan’s population is already 65 or older, so perhaps that gives us one indication—but Japan is a highly-developed country. What will China look like when its demographics look similar to Japan’s today (which is projected to happen by 2050)? Or much-poorer Cuba, which will hit the same milestone at roughly the same time? These are important questions that we don’t know good answers to—but they’re also the frame we’re most familiar with.

But that’s not the only frame. The piece also points out that a number of countries are currently in or approaching the sweet spot for a “demographic dividend.” That phrase describes a temporary demographic situation, about a decade or so after a dramatic fall in fertility, where the ratio of dependents to workers is historically low and the working-age percentage of the population is exceptionally high. This position provides a unique one-time opportunity for rapid economic development if a country can take advantage of it with policies that harness a capable workforce to move up the value chain. But it really is a one-time opportunity, because as that workforce ages, the dependency ratio rises rapidly, and consumption begins to outpace investment, putting a drag on the economy. And that drag will come whether a country seizes the development opportunity or not, which means there could be wide and permanent economic divergence between different societies that make that transition but take different policy approaches in response to that opportunity. Vietnam and Iran, for example, are countries that are in the zone now, and don’t have much time to make that policy leap before the opportunity passes them by. Meanwhile, until somebody finds a reliable policy lever to raise fertility up to roughly the replacement level, the far side of the demographic transition looks like a permanent trap of aging and shrinking societies.

Those divergences have profound implications for investors, which the Times piece highlighted. But they also have profound geopolitical implications, both because of the potentially large divergence in economic power between countries as a result of this transition and because wars are fought primarily by younger people. Of course, as the Russia-Ukraine war demonstrates, it is possible for two shrinking countries on the far side of the demographic transition to fight a war with each other. But the demographic cost of that war is not a trivial factor to weigh when considering the likelihood of either side prevailing—particularly for Ukraine. Ukraine’s total population is roughly 25% of the size of Russia’s. But its prime military-age population (aged 20-39) is even smaller—20% the size of Russia’s. Its population of men in their 20s is smaller still—16% the size of Russia’s. Ukraine has the force multiplier of superior technology and the morale advantage of fighting for the defense of their country, and both have demonstrated their importance in dramatic fashion. But over time the sheer weight of demography is exceedingly hard to overcome.

With that fact in mind, I went down a rabbit hole and looked at China’s demographic picture as it compares with a variety of possible competitors or constellations thereof.

First, I looked at China in comparison to India—the country that just surpassed it as the most-populous country in the world. China and India had almost identical populations in 2020 (the base year that I used for comparison), and they also had almost identical prime working age populations. (I used ages 20-54 for prime working age, which skews a bit younger than the standard American demographic definition. As an aside, I’m getting all my demographic information from the Population Pyramid website, which is relying on the United Nations population projections.) Both numbers are going to diverge in years to come—but the working-age population is going to diverge more dramatically more quickly. By 2050, India’s population will have grown modestly while China’s will have shrunk modestly, with the result that India will be 27% more populous than China. But India’s prime working-age population will have grown along with its overall population, while China’s will have shrunk by over 30%, with the result that India’s prime working-age population will be 60% larger than China’s. By 2100, meanwhile, China’s overall population will have shrunk to just over half its 2020 size—but its prime working age population will have shrunk to only a third of its 2020 size. India’s prime working age population, meanwhile, will be about 85% of its 2020 size in 2100—and nearly 240% the size of China’s.

The difference between having prime working-age populations that are comparable in size and India’s being nearly two-and-a-half times larger is simply staggering. Of course, projections three quarters of a century into the future are obviously uncertain. But they aren’t random guesses; the UN’s projections are not only pretty much the best guess we have but have had a pretty decent track record. Moreover, much of what is projected to mid-century is already baked in the cake; the prime-age workers of 2050 have all already been born. So if we take the century-end projections seriously as well, then it looks like even regional Chinese hegemony would be short-lived at best in the face of a rising India. Even if India’s development stalls out short of where China ultimately lands (as China may stall out short of where Japan landed), the prospective economic and geopolitical challenge that India poses to China is likely to be comparable to the one that China has posed to the United States and its allies.

That, in turn, is one reason why the United States should dispense with fantasies of India becoming one of those allies. India has always fiercely prized its independence, but today it is also highly cognizant of its status as a rising Great Power, potentially one of the world’s handful of dominant powers. There is no chance that it will subordinate its ambitions to America’s, any more than China did after the Nixon-Kissinger era thaw or the Clinton-Bush era embrace. The United States can certainly partner with India where we have interests in common, and balancing China is absolutely one of those interests. But what India wants from that relationship is what China wanted: to achieve its potential in terms of economic and geopolitical power. That potential being as enormous as it is, India has no reason to follow American leadership more generally. So they haven’t (e.g., on Russia) and they won’t.

Speaking of the United States and China, the comparative demographic projections for the two countries are similarly eye-opening. My expectation a decade ago was that China would inevitably surpass the United States as the world’s largest economy and, after that, would eventually become the world’s most powerful country. A power transition being a tricky thing, I fretted about our ability to manage it without catastrophe. In the fullness of time, though, it’s become less clear whether the transition will happen at all. China may or may not already have become the world’s largest economy (it depends on how you measure), but if it hasn’t it may never happen—and the more seriously one takes these longer-term demographic projections, the less plausible it seems.

The United States’ population is projected to continue growing modestly even as it ages, largely because of immigration (since American fertility is now below replacement, albeit much higher than China’s). Because of this, America’s prime working-age population is expected to remain relatively stable over the rest of the century; it will be slightly larger in 2050 than it was in 2020, and by 2100 it will have fallen slightly from there, roughly back to its 2020 level. Since China’s prime working age population is projected to collapse over this period, however, the ratio between our two countries on this metric is projected to become vastly more favorable to America. America’s population was roughly 24% of China’s in 2020, and its prime working-age population was 21%. By 2050, America’s population will be 29% the size of China’s and its prime working-age population will be 32% the size of China’s. But by 2100, America’s population will be fully half the size of China’s—and its prime working-age population will be over 60% the size of China’s. Unless China’s economic development carries it to or near parity in spite of the powerful drag of an unfavorable dependency ratio (which seems unlikely), the long-term prospects for America’s continued supremacy (though not dominance) look better than I had previously imagined.

That projection should make Americans considerably less-worried about the prospect of living in a China-dominated world for the foreseeable future. However, it’s also a key reason why many observers are concerned about the near-term possibility of Chinese bellicosity. It may seem strange to put it that way, given China’s existing and growing advantages in the primary potential arena of conflict: Taiwan. The military and economic balance between China and Taiwan has already shifted so overwhelmingly in China’s favor that, if left to its own devices, the island would have no choice but to surrender in a conflict—and the balance is only going to shift further given China’s continued development and military buildup and Taiwan’s projected demographic collapse. That means that Taiwan’s defense depends overwhelmingly on American support. So if China were confident about becoming the dominant economic and military power in the western Pacific over the next 10-15 years, such that it would be less and less plausible over time for America to commit to defending Taiwan, it would be extremely foolish for them to act precipitately, even in the face of American attempts to build a robust anti-Chinese coalition. As I’ve argued before in this space, military aggression under contemporary conditions is far more likely to harm the aggressor’s prospects than to enhance them, and that applies just as well to China vis a vis Taiwan as it does to Russia/Ukraine and America/Iraq.

But if China looks further down the road, they may see their power as potentially already near-peak in global terms. Worse, in the latter half of the 21st century they may see the power balance versus the United States shifting back dramatically in America’s favor—and that would rationally change their calculus of what to do today. Precipitate action, against Taiwan or, even more so, against American assets directly, would still be incredibly risky, but doing something becomes more imperative if it no longer looks like a waiting game will pay off. In fact, that may be precisely the kind of thinking that prompted Russia’s Vladimir Putin to invade Ukraine.

Other great powers like India and America aren’t the only relevant comparison to make vis-a-vis China, though. China is the greatest Asian development success story to date because of its sheer scale, but there are numerous potential competitors right on China’s doorstep poised to surge forward, whose economic and political trajectories could be as decisive in shaping the geopolitics of the western Pacific as anything China, America or India does. So I next compared China to the developing nations of Southeast Asia, which I construed broadly to include: Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Myanmar and Bangladesh. (I excluded the most developed countries of the region because I wanted to treat them in a separate grouping.)

Unlike India and America, Southeast Asia isn’t a unified country. It isn’t even a cultural, economic or political bloc. It includes monarchies, democracies and Communist dictatorships, countries that are predominantly Catholic, Muslim, Buddhist, and irreligious. Its linguistic diversity is literally among the widest on the planet. The most-populous country in this group has over 250 million people and the smallest less just over 7 million; the wealthiest (Malaysia) has a per-capita GDP of over $11,000 in PPP terms, which is just below China’s, while the poorest (Myanmar) has a per-capita GDP just a bit over 1/10th as high. This region is an increasing focus for investors looking for alternatives to China to locate their supply chains, places that are be cheaper, pose less of a direct competitive threat in the immediate future, and carry less of the unique geopolitical risk associated with China’s government and its rivalry with the United States. As well, these countries are already all a focus of geopolitical competition between the United States and China. Finally, many of them are either right in that sweet spot for the demographic dividend or will soon enter it; only one (Thailand) may already have missed that boat. So how does this region compare with China?

As of 2020, Southeast Asia (as I have defined the region) has a population a bit under 60% the size of China’s, and a prime working-age population that is also just under 60% the size of China’s. But its population is still growing, while China’s has already begun to shrink—and, as you would expect, the difference is even more dramatic when we look at prime working-age people. By 2050, the region’s population will be 75% as large as China’s and its prime working-age population will be over 90% as large as China’s. By 2100, its population will be lower than it was in 2050, and its prime working-age population will be lower than it was in 2020. But China will be shrinking so much faster and more dramatically that Southeast Asia’s population will be nearly 20% larger than China overall, and its prime working-age population will be 45% larger than China’s.

If China were still projected to grow demographically, albeit more slowly than its Southeast Asian neighbors, and if it were projected to clearly outpace them economically, then it might be plausible to project that that China would achieve greater and greater dominance over the region as the century wore on—though it’s worth noting that America’s dominant influence over Latin America has waned considerably over a period that could be described in very similar terms. But the Southeast Asian region is demographically poised for takeoff development even as China ages into what is likely to be a less-dynamic development phase. If the Sino-U.S. rivalry continues to intensify, some countries in the region may line up neatly behind one power or the other, but the wisest move for most states would be to focus on maximizing their own development while the demographic going is good, and avoid being locked in to one or another bloc. If large countries like Indonesia can achieve a true economic takeoff, they may well not only be able avoid being dominated by either China or America but to play a substantial role in their own right in shaping their regional environment. Regardless, though, the prospect for long-term Chinese regional hegemony looks far less plausible when the scale of the independent potential of the neighbors it might aim to dominate becomes clear.

Finally, I was very curious to compare China to the developed countries of the western Pacific, because these are the countries that are most directly threatened by China’s rise. Japan, in particular, has played an outsized economic role throughout East Asia because of its substantial development lead over the rest of the region, but as China joins the ranks of developed nations, Japan’s relative position has dwindled, and it has consequently become far more interested in deepening its alliance with America. So, while in aggregate they are much smaller than China demographically, and are already on the far side of the demographic transition, I thought it was worth comparing China’s trajectory with the following group of highly developed countries: Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand.

What was interesting to see was that, notwithstanding the fact that most of these nations are projected to shrink in size through 2050 and 2100—some (like South Korea and Taiwan) alarmingly so—in percentage terms China is still expected to shrink more. And, once again, the effect is even more dramatic when we look only at the prime working-age population. As of 2020, the combined population of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand was only 17% the size of China’s, and its combined prime working-age population was only 15% the size of China’s. By 2050 little will have changed; China’s overall population will have shrunk 8% and its prime working-age population will have shrunk 31%, while its developed neighbors will have shrunk 9% and their prime working-age populations will have shrunk 28%. But by 2100, China’s demographic collapse will have far outpaced these competitors, with its overall population dropping nearly by half and its prime working-age population falling by nearly two-thirds, compared with a drop of less than one-third and less than one-half for its developed rivals. By 2100, the combined prime working-age population of these developed rivals of China’s will have grown in relative terms from 15% the size of China’s to 23%, despite a precipitous absolute decline.

Most of the countries in this group are explicitly American-aligned, so the risk to America in the context of a rising China has been on the one hand that their defense will get increasingly burdensome and, on the other hand, that the seeming inevitability of China’s eventual dominance of the region would create a powerful undertow toward bandwagoning. These countries’ maturity and their declining demographic future would seem to reinforce that prospect—but everything is relative. It makes little sense to get on a bandwagon that you expect to go backwards. The demographic prospects of the two countries most vulnerable to Chinese pressure—Taiwan and South Korea—are bleak in the extreme, but America’s two most important allies in the group—Japan and Australia—are in considerably better shape compared with China. Japan is projected to shrink dramatically over the rest of the century, but in spite of shrinking by more than 50% its prime working-age population will go from 7% as large as China’s to 10%. Australia, meanwhile, is one of the few developed countries whose prime working-age population is projected to grow through 2100. Currently, its prime working-age population is less than 1/2 the size of South Korea’s and roughly the same size as Taiwan’s; by the end of the century, it will be 10% larger than both of their prime working-age populations combined.

That was a long rabbit hole to go down—but at the end of the journey a few things are clear. While we could still see a climactic contest between China and America for dominance of the western Pacific, an alternative and arguably more likely future is far more complex and multi-faceted. If the United States and China can get through the next decade or so without a catastrophic war, we could enter a world where America continues to outpace China as a geopolitical force, with developed allies in the region that are increasingly confident in sustaining that alignment, while, at the same time, a rising India and a rapidly developing Southeast Asia make both Chinese regional hegemony thoroughly implausible and simultaneously undermine American pretensions to sustaining that position in its own right.

I find that prospect reassuring, personally, because I find both the prospect of a Chinese-dominated future and the prospect of a bipolar world structured around U.S.-Chinese rivalry to be alarming in different ways. I would far prefer the United States to be the most-potent power in a genuinely multipolar world than either play second fiddle to a Chinese dictatorship or shoulder the burden of leadership of the free world in a new Cold War. Entering that world would mean we would have to learn to treat other countries as something like equals, something America has never been good at. But maybe we could learn.

At a minimum, it would be a good idea to try before the arrival of the African Century upends our comfortable assumptions that the western Pacific is where the future lies. Because that’s the thing about the future: they keep making more of it.

"I would far prefer the United States to be the most-potent power in a genuinely multipolar world than either play second fiddle to a Chinese dictatorship or shoulder the burden of leadership of the free world in a new Cold War. "

If handled properly, I would like this as well, if for no other reason that that multipolar world is by far the likeliest future, given demographic and economic trends.

But let's not assume that such a multipolar world lends itself to stability, compared to the two other possibilities. Multipolar worlds, with rising and falling powers and no dominant ones, often lead to arms races and heightened tensions, as we saw with the rise of Wilhelmine Germany and the (relative) decline of Great Britain before WWI.

This *could* be a peaceful world if the US were to become an able balancer among conflicting and rivalrous forces in the Indo-Pacific. But in our history we've never shown the ability to do that. We've either withdrawn from the world (19th century; between WWI and WWII) or we join in but only to lead great crusades (WWII, the Cold War, the Global War on Terror). We don't do subtle; we don't do balancing.

Can we learn new foreign policy skills? I guess we'll see.

Does the analysis change if one considers also (for example) China’s investments outside of China. Owning much of the US debt, purchasing priory and land, winning bids for concesionarios e.g. building and managing sea ports, running electrical companies in e.g. Chile ... ?