Hot Wrap

New York got rain and a respite; the nation, not so much

This has been a light week over here, but a busy week for me elsewhere.

Breaking Up Is Hard To Do

The New York Times has been running a series of essays running weekly during the summer starting this past Independence Day under the overall banner of “Snap Out of It, America!” Ezekiel Kweku, politics editor of the Opinion page, describes the purpose of the the series as follows:

America used to be a young country. And in its youth, it changed as it grew, the idea of what was American as malleable as the idea of what was America. The country expanded its borders, abolished slavery, broadened the franchise; waves of immigrants reshaped and revised America’s character; the government added and dropped functions, amending the Constitution to fit the times. It was a restless experiment.

Kweku continues:

Not all of the big changes were completely — or even ambiguously — good. The economic boom of the industrial age was fueled by the blood and sweat of exploited workers; the country’s westward expansion came at the expense of Native Americans. But America in its youth was a country confident and unafraid to confront the future. What if it could recover that spirit of invention and restlessness, the risk-taking that formed this country? What would it change? What could it be?

I was one of those solicited to contribute an essay, which ran this past Wednesday on line and Thursday in print. My chosen topic: We should reorganize the country by breaking up the largest states.

The argument has roughly four parts:

A breakup is necessary to provide something resembling adequate representation to the citizens of the largest states via the Senate, since each state must have an equal number of senators (and this cannot be changed via constitutional amendment).

It would reduce the ability of the largest megastates to effectively set or thwart national policy unilaterally by virtue of their sheer bulk.

It would enable disparate regions of large states to govern themselves, and would allow for the creation of city-states from the largest cities.

It would facilitate the development of structures for regional coordination based around actual economic regions rather than the current states.

As they say: read the whole thing.

Of course, an opinion piece is obviously not a blueprint, and isn’t intended to be, nor is it intended as a manifesto. It’s intended to be a conversation starter. The editors at The New York Times were looking for blue-sky ideas, and that’s what this was intended to be.

But it does make a couple of crucial concessions to reality that few proposals of this kind tend to do: it pays attention to the actual text of the constitution, and it pays attention to the partisan consequences of such a reform. A lot of other reform proposals that I’ve read recently basically ignore both, imagining a constitution for a country that does not exist or advocating reforms with a blatantly partisan purpose. If we intend to remain one country, though, I think it behooves us to argue in a different spirit, and that’s what I’ve tried to do.

On Friday, I was interviewed on Michael Medved’s show, MedHead, about the piece, though we also touched on other matters like dialogue-free movies about farm animals and also my latest at The Week.

Europe’s Right Turn

That column is about the prospect of Europe becoming more right-wing than the United States, and how the American left might handle it (assuming anyone notices).

The predictive claim in the column leans heavily on recent opinion polls, but those are really a fickle and mixed bag. Italy’s far right looks very much on the upswing right now; in France, by contrast, the biggest polling news is the rise of the moderate right; and in Germany, it wasn’t that long ago that a Greens-led government seemed a real possibility. But I think it’s worth taking a longer view. In certain ways, Europe is already more conservative than the United States. For example, the ECB took a more austerity-minded, bank-friendly attitude to the financial crisis and its aftermath than did the U.S. Fed or the Obama Treasury Department, and Europe’s national governments have been less generous with handing out cash during the COVID recession than Washington was.

But what’s really distinctive about Europe is that much of the European left has collapsed. The three parties in most serious contention for the French presidency, for example, are the governing centrist En Marche, the center-right Republicains, which have been showing new strength, and the far-right National Rally, which is expected to lose but to do better than it did in the last election. Yes, the National Rally has both moderated somewhat on the question of Europe, and it also did very poorly in recent local elections. But new figures even further right are emerging, and more notably French centrists are denouncing Critical Race Theory as a dangerous foreign import that threatens the integrity of the republic.

Meanwhile, in Denmark, the ruling Social Democrats are making tough immigration laws even tougher, sending asylum seekers out of Europe entirely.

In the big picture, then, I think Europe’s primary preoccupations are going revolve around right-wing issues. Those issues may be addressed by more mainstream parties rather than parties of the far right, in part as a strategy to take the wind out of the far right’s sails. I hope that’s precisely what happens, in fact. But if those are the focal issues, then Europe will be a fundamentally more right-wing place.

I really do wonder whether the American left and center-left will notice, and how they will assimilate that fact. I hope they take to heart the fate of the European left, and the fact that denunciations of a certain set of left-wing American arguments are coming from centrist European statesmen and not just from Fox News, and rethink their own views, and not just their style of expression, accordingly.

Ideological Consistency is the Hobgoblin of Little Centrism

My one post On Here this week was about the debate about whether the left has moved further left or the right further right over the past however many years, and therefore who is to “blame” for the culture war. I find this framing really unhelpful, and if you want to know why I encourage you to read the piece.

Getting the story right has important implications for whether and how the American left can learn from the European left’s failures. My read on what happened to the Democratic Party is that it became less cross-pressured. Increasingly, Democrats bought into a whole ideological worldview encompassing liberal stances on a host of unrelated issues. That’s really what the data shows, not that Democrats have done off the loony deep end, but that the center has to some degree emptied out as previously cross-pressured voters have sorted themselves into consistent liberals or conservatives.

That has real implications for how the left can change. In the early 1990s, there were plenty of voters in the center, and so when the Democrats found themselves consistently losing national elections, they could simply move more to the center, find more votes there, and win. Republicans did the same thing in the early 2000s—there were definitely extreme things about the Bush administration, but there were many ways in which it reflected the center of the country at the time.

If the center is actually hollowed out, though, then it’s not enough for the party to move to the center, because the votes aren’t there. Rather, liberals themselves have to change their minds about certain things, not just prudentially as a way to make inroads with more centrist voters, but so as to become more centrist voters.

This may already be happening, specifically around issues of public safety. And there may be other issues on the way. Maybe I’m just an over-informed New Yorker aware that the final two candidates in our Democratic mayoral primary were the winner, Eric Adams, who ran explicitly against defunding the police and a number of other novel left-wing shibboleths, and the close second, Kathryn Garcia, who was less voluble in her opposition but had positions on issues like public safety, education and development very similar to those taken by Adams; but I suspect that there is a sizable contingent of Democratic voters—a silent majority, you might call them—who hadn’t thought much about the subject until the last year or two, but who when push comes to shove just don’t agree with some of the tenets of contemporary woke liberalism. Not the style: the tenets. If primary fights over these issues start happening inside the Democratic tent, it might be startling how quickly the landscape shifts.

The World Elsewhere

On the same topic of our political divisions, Echelon Insights put out their latest survey which they have sliced and diced in all kinds of interesting ways. Their big takeaway is that America is majority economically progressive but culturally conservative. I think this is incorrect: the percentage of Americans who hold economically progressive and culturally conservative views is very small (though much bigger than the percentage of those who hold the opposite). Rather, there is no center: the distribution of American voters is barbelled. I have all kinds of thoughts, which I duly tweeted. Here’s the first tweet of the thread; click to read it all:

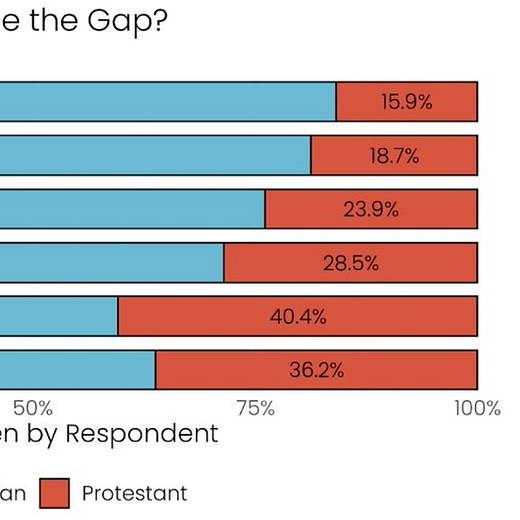

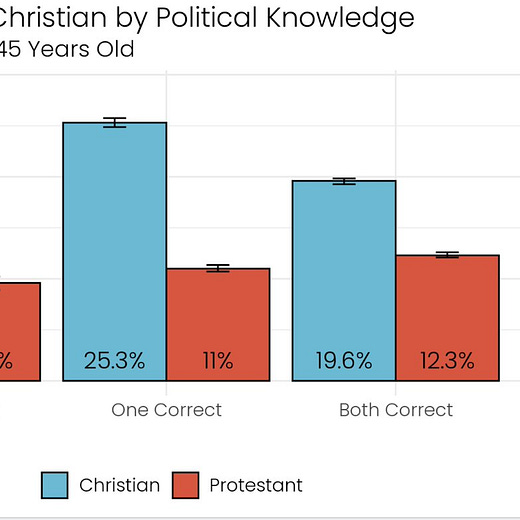

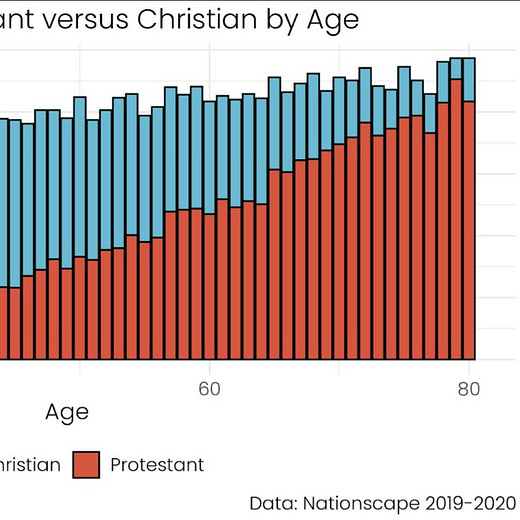

The other big survey that everyone has been talking about is about the possible revival of the Protestant mainline. Over the past 2-3 years, the percentage of White Americans who identify as evangelical Christian has continued to shrink—but, in a reversal of previous trends, the ranks of the unaffiliated have dropped while the percentage who identify as non-evangelical Christians has risen—in both cases quite sharply. There are a lot of questions to ask about the data—whether the change reflects any shift in denominational affiliation, for example, or whether it’s just a shift in nomenclature by people who rarely attend church or are unaware of denominational lines in the first place. When increasing proportions of American Christians don’t seem to know what a Protestant is, it’s hard to know what the results of this kind of survey mean. But it’s certainly worth watching.

On the subject of public safety, The Washington Post had a fascinating piece on the sharp rise in gun ownership—particularly first-time gun ownership—during the pandemic year. The anecdotes are really something—a trans activist who bought a gun to ward off right-wing counter-protesters?—but the real question is how big the phenomenon really is, how enduring it turns out to be, and whether it winds up fueling more change to the politics of guns, or to the politics of public safety.

And on the subject of religion, Ross Douthat penned a fascinating taxonomy for First Things of the new political divisions within American Catholicism. I have no informed opinion about any of the divisions he describes, but I heartily endorse the larger framework of thinking about the inevitable demographic and institutional reality and how these divisions might play out in that context rather in the void of cyberspace.

Finally, do you remember “Cat Person,” the world’s first viral New Yorker short story? Well, there’s a new piece in Slate by a woman who was mortified to realize that she, and a relationship she had been in, served as a key model for the story—mortified to see her private life laid out that way but even more mortified to find the relationship itself unrecognizable based on her experience. I think the piece is very worth reading, but it has driven some really bad takes on “Cat Person” and on fiction more generally, about which I have thoughts. Which I tweeted. Here’s the first tweet of the thread; click to read it all:

Stay cool, people, and stay out of Death Valley.