Growth Is Up. So What's Up With the Economy?

Expectations are wildly out of line with their historical relationship to reality. Why?

I’m going to take a break from brooding on the horrible events in the Middle East to remind myself and others that there are other news stories in the world. And, notwithstanding all the terrible things going on in America and elsewhere, today’s big news story is the extraordinary strength of the American economy.

I don’t think we should minimize that strength. America’s economic performance since the end of the pandemic has substantially outpaced the rest of the developed world and has also very substantially bested the performance of the Chinese economy. Inflation is still elevated, but is well below the post-pandemic peaks; meanwhile, unemployment is extraordinarily low despite substantial increases in interest rates. Consumer spending is high, businesses are investing—it’s really been an extraordinary recovery.

But it doesn’t feel like that to people. Have people’s perceptions come completely untethered from reality? Or are we missing something from the data?

Jonathan Last has a piece at The Bulwark arguing the former. Yes, there are problems with the economy—inflation remains above the desired level, housing is very expensive, the backup in rates has made moving uneconomical for many people, etc. But none of these problems come close to justifying the level of pessimism, rage and despair we see in opinion surveys. Last includes two charts in particular that are worthy of note: one comparing how small businesses are investing and hiring versus what they say their expectations are, the other comparing an index of data affecting consumer well-being with a chart of consumer sentiment. In both cases, the two sets of data tracked reasonably well through 2020, and have since diverged dramatically. Last declines to offer much in the way of explanation of what might be going on, concluding simply that people’s perceptions have departed from reality and that this, in itself, is a huge problem.

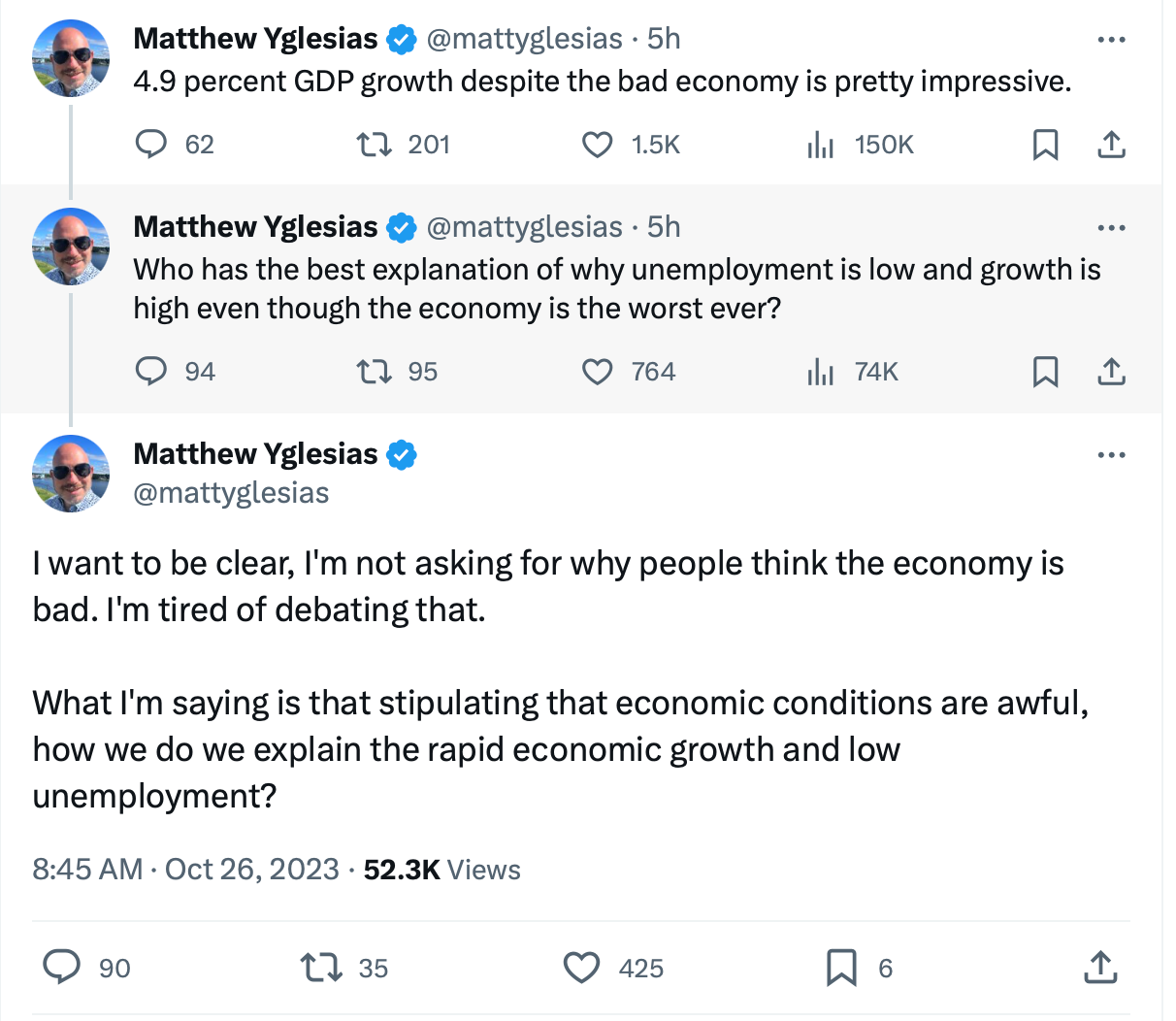

Coming at the problem from the other end, Matt Yglesias tweeted the following:

Instead of asking “what has gone wrong with our perception,” Yglesias asks for suggestions—any suggestions—of what might be wrong with the data. How is it possible that economic conditions are actually awful when the data keeps saying that they are really, really good? How could so much of the data be so good if the economy is actually awful?

I’m going to do my best to answer the question from both ends.

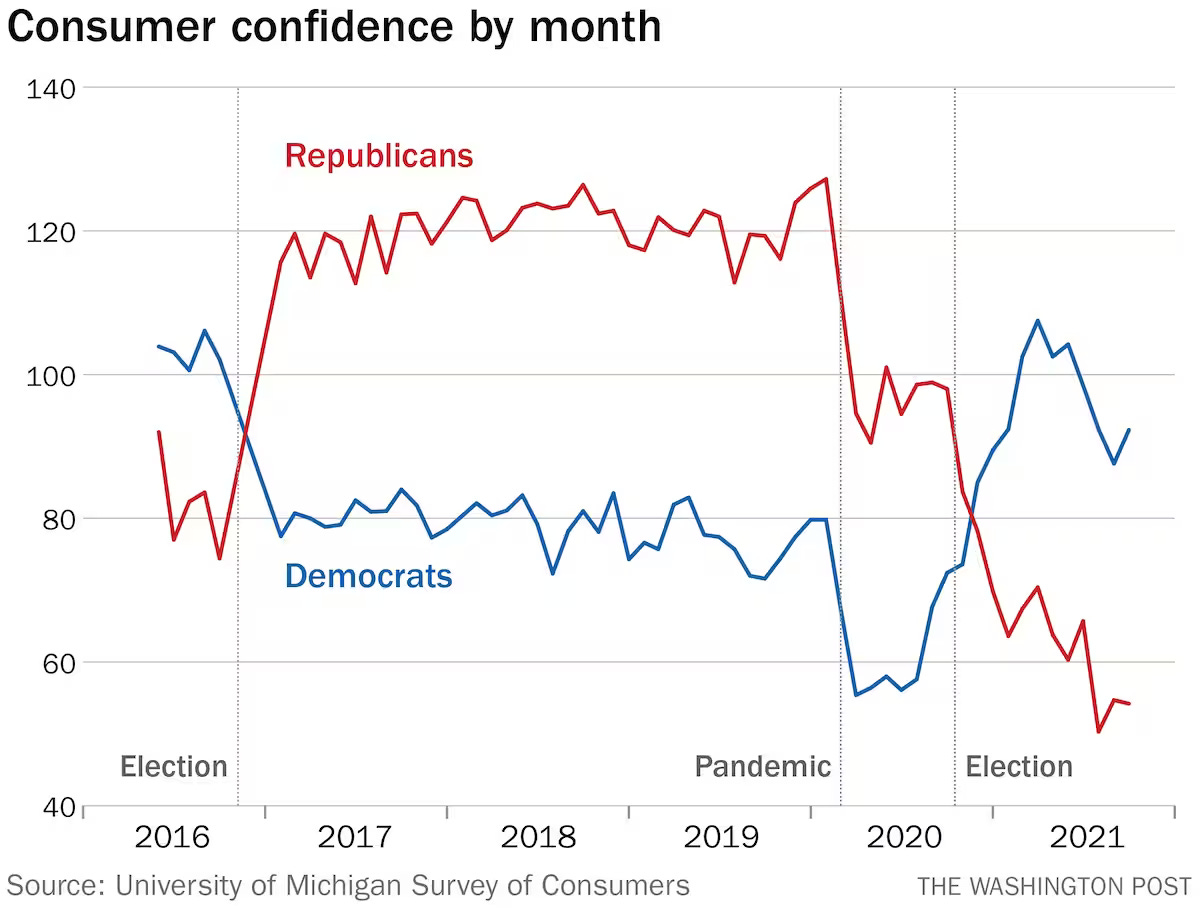

On the perception side, one factor is surely political polarization. We’ve all seen charts like this one, from The Washington Post, showing how popular views of the economy are profoundly and instantaneously shaped by the party of the president:

When Donald Trump was elected, Republican confidence soared and Democratic views cratered. When Joe Biden was elected, the opposite happened. That certainly doesn’t speak well of the quality of the data in consumer confidence surveys. And if people aren’t acting, economically, on their bad feelings—as robust spending and small-business investment suggest they aren’t—then perhaps it doesn’t matter? A refusal to hold the parties to account for their economic performance would be bad for democratic accountability, but maybe that insulation would just mean that politicians could leave macroeconomic management even more completely in the hands of the Fed’s bureaucrats. Who knows?

I’m skeptical of this explanation for where we are specifically, though, for two reasons. For one thing, polarization should cancel out. Democrats should overestimate the economy now and Republicans should underestimate it, and the average of the two should approximate reality. Instead, we’re seeing a sharp divergence between average consumer views and the economic fundamentals, and a dramatic voter preference for Republicans on the issue of the economy specifically. That doesn’t look like polarization in action—it looks like accountability for an economy that people genuinely believe is bad.

Perhaps President Biden is a victim of a distorted media narrative? Right-wing media reliably boosts Republicans by calling the economy terrible when Democrats are in charge but calling it wonderful when Republicans are in charge; meanwhile, the mainstream media is biased toward negative stories all the time because bad news travels better, and progressive media is biased toward negative stories because they believe that the perception of problems motivates political action, while good news breeds complacency. The first two phenomena, though, aren’t new, and yet both John Kerry in 2004 (who lost) and Barack Obama in 2012 (who won) slightly outperformed the economic fundamentals. And I find it very hard to believe that the difference today is the extraordinary reach and power of counterproductive messaging by progressive media.

I’m not saying that political biases can’t have anything to do with the enormous gap between perception and apparent reality. But there must be more going on.

The most obvious two factors are the hangover from the pandemic and the effect of inflation. People got a lot of free money during the pandemic and had little to spend it on; household savings went through the roof. Intellectually, people surely knew this was temporary, but nonetheless I’m sure people feel shitty about pandemic assistance ending, the rise in prices now that they can actually buy stuff, and the drawdown of their savings. Even if wages are rising, they feel poorer because of irrationally rising expectations.

That’s not the whole story about the pandemic hangover, though, because that hangover isn’t just a matter of perception. Consumer spending has surged even as real income growth has been tepid and the personal savings rate has fallen:

That combination suggests that consumers may have established unsustainable consumption patterns in the wake of the pandemic, through a combination of pent-up demand from a period when there was no way to spend money and a fuzzy notion of how long pandemic savings would actually last—or, better, a fuzzy expectation that after the pandemic a recovery would mean earned income would completely make up for the funds previously provided by government assistance. That isn’t what happened, and that failure is not only a negative shock to expectations, it’s a very real pressure for retrenchment and cutting personal spending. If wages are up and jobs are readily available, the need to nonetheless cut back on spending is going to feel particularly irksome, a sign of something very wrong in the economy. That’s particularly true if rent is the thing you are feeling painful pressure to cut back on.

Next, consider the effect of inflation. There’s a certainly a psychological component to how people react to inflation; our perception of prices is sticky, so when the economy goes through a bout of inflation, things continually surprise us with their cost even if they are actually still affordable. Given that, as inflation has fallen, wages have not only kept pace but surpassed inflation, there’s a natural tendency to say that the anger about inflation is entirely a matter of psychological biases. But that’s not the whole story either.

Significant inflation can create a large number of losers even if wages in aggregate keep pace. The reason is that average wages are just that: an average. Half the data points are above average, and half of them are below average. That means that if wages in aggregate keep pace with inflation, for something like half of the population wages have lagged inflation, while for the other half wages have outpaced. This is true even within income quartiles: yes, the lowest-earning quartile’s wages have outpaced inflation more than the other quartiles, but you’d expect to see the same divergence within that quartile, with half being below that quartile’s average and half above. So even if the aggregate numbers are good, there are likely very large numbers of people for whom the numbers are bad.

This is notably different from what happens when unemployment rises, where the pain is highly concentrated in those who actually lose jobs (though of course not limited to them). In fact, that difference has everything to do with why bouts of inflation piss people off so much. Wages are famously sticky, so almost nobody experiences nominal wage declines without losing their job. That’s one explanation for why we have recessions at all: because what the economy “needs” is real wage declines, but the zero bound for interest rates and sticky wages make that impossible, so instead we get a recession and unemployment. But when inflation is higher, you can have real wage declines even if nominal wages hold up. You can have it across the economy, but you can also have it in specific sectors, or just for specific people—if you don’t get a raise because of mediocre performance, suddenly your real income has gone down. That can only happen when inflation is significantly positive, like it is now.

All I’m saying is that the pain of inflation is more spread out than the pain of unemployment. From a utilitarian perspective, that’s arguably a reason to prefer inflation to unemployment, all else being equal; the long-term social and economic consequences of unemployment are horrific, far worse than what we’re now experiencing from inflation. But even if spreading the pain out means avoiding those horrific consequences, it still means a whole lot more people experiencing pain.

On top of all that, there’s the effect of uncertainty. In a disinflationary environment, economic conditions are getting progressively more stable and predictable. They may be better or worse, but they’re not terribly surprising. Inflation messes with that; the wild dislocations of the pandemic messed with it far worse. The result, though, is that people genuinely don’t know what to expect as well as they used to. Even if their personal situation is objectively good, they might not have the kind of confidence that it will endure that they normally would because they simply don’t know what’s going to happen next—the imaginable outcomes have a wider distribution than they used to. The chart from The Economist that Last includes, showing how consumer sentiment has diverged radically from the fundamentals, is based on data from 1980 to 2016—a long disinflationary period in American history.

Maybe if they used data from 1968 to 1982, they’d have seen a different result.

Speaking of 1968, there is an objective measure of economic fragility to point to that would justify real concern about the economy, and that wouldn’t show up in growth or unemployment figures—yet. That’s the unsustainable nature of America’s fiscal situation.

In 1968, unemployment was 3.4%, GDP growth was 4.9%, and inflation was 4.2%. Sound familiar? But the economic situation in 1968 was quite precarious. President Johnson’s guns-and-butter policy led to persistent deficits and pressure on the dollar, leading to a series of crises that culminated in Richard Nixon taking America off the gold standard in 1973. 1968 was the beginning of the end of the long post-war boom in America—but, just looking at those three headline figures for unemployment, growth and inflation, you might never have guessed.

I’m not suggesting that contemporary conditions are identical or even really comparable to 1968. However, the United States is running a $2 trillion deficit when the economy is apparently going gangbusters and inflation is still elevated. That’s not just macroeconomic mismanagement—it’s a good reason to disbelieve in the sustainability or even the reality of the strong economy. Maybe it’s all a deficit-financed illusion about to come crashing down?

I think that worry has a lot to do with why small-business-owners and corporate executives have been so pessimistic, besides their political biases. True, the fiscal situation isn’t as dire as it was in the early 1990s, and the economic situation certainly isn’t what it was in the 1970s. But the fiscal picture could deteriorate rapidly if nothing changes—interest payments are already up to 2.5% of GDP, which is where they were in the early 1980s.

George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton navigated our last era of necessary fiscal retrenchment through a combination of tax hikes and spending cuts. Johnson tried to resolve his own budget problems in 1967 with a significant tax increase, but was rebuffed by Congress. I think it’s safe to say that America’s political system is dramatically less capable of cooperatively resolving these kinds of problems than it was in either era.

Again, I don’t want to exaggerate the seriousness of the situation or to say that it justifies seeing our economy as terrible. The economy is clearly not terrible. But just as you can’t evaluate the health of the economy without reference to the past—you need to know not only what the unemployment, growth and inflation rates are, but what they have been, whether they are rising or falling and how rapidly they are doing so—you can’t do so without reference to expectations for the future. There are rational reasons to worry about the stability of the economy beyond the worry that the Fed will tip us into recession by hiking rates too aggressively. And even if you don’t know where it’s coming from, you may get a whiff of fear in the air.

That stink is part of the economic picture too—and it likely has political consequences.

"All I’m saying is that the pain of inflation is more spread out than the pain of unemployment."

But is this really true? Seeing the unemployment rate climb increases your perceived estimate of the risk of losing your own job which, even if the probability isn't that high, exacts a much greater cost than gas costing a dollar more per gallon at the pump. Or maybe your child is graduating from college into the Great Recession and not only can't get a job but is at risk of her entire career path being permanently wounded, and you deeply feel the pain of your child (or of your close friend or relative who *did* lose their job).

Bottom line: perceiving the current economy as being as bad (or worse!) than during the Great Recession is almost definitive proof of some kind of psychological breakdown in the polity. No matter what happened to the price of eggs.

"There are rational reasons to worry about the stability of the economy beyond the worry that the Fed will tip us into recession by hiking rates too aggressively. And even if you don’t know where it’s coming from, you may get a whiff of fear in the air."

Does that explain why so many people's IRAs & 401s are merely treading water?