Genghis Khan vs. George Washington

Who was more consequential, the great conqueror with the enormous genetic legacy, or the childless man who declined to become an emperor at all?

I’m as revolted as many other observers by that 2021 J.D. Vance clip now making the rounds saying women like Kamala Harris are “childless cat ladies” who have no stake in the future of the country because of their childlessness, who are also personally miserable and therefore want to make everyone else miserable like them. If you want a pitch-perfect response from a pro-natalist, Christian, rightward-leaning and self-respecting woman, Bonnie Kristian has got you covered.

Myself, I’d only add that to the extent that Vance has a point, he doesn’t go far enough. What’s so special about childless women? To a first approximation, we’re all miserable, and we’re all trying to validate our lives by making everyone else miserable in the same way we are. Married people and single people, working-class folks and highly-educated folks, deeply religious people and dogmatic atheists: no matter who we are or what our station is in life, most of us feel like losers and failures at least some of the time—and we often deal with that feeling by convincing ourselves that at least what we did was right, while the people who seem happier and more successful are lying, cheating or both. Vance certainly is doing exactly that. I don’t know whether Vance personally is miserable and consumed with resentment, but his whole schtick plays into precisely those feelings of righteous failure. You think anyone happy with their life wants to swallow the kind of crap he’s dishing out?

But at the risk of taking Vance seriously if not literally, I’d like to dig a little deeper.

There are a lot of reasons to want children, and a lot of reasons to worry that our culture doesn’t make it either financially or psychologically easy enough to embrace parenting, either for men or for women. Count me as one of those who thinks that’s a serious enough problem to merit a sustained policy response, even though I am skeptical of such a policy response’s likely success. For a certain kind of man who I imagine might be nodding along with Vance’s contemptuous remarks, Harris isn’t just someone who married too late to bear children, and is therefore someone they don’t want their daughters following in the footsteps of. That’s not remotely a deep enough vein for this kind of nastiness. She’s somehow to blame for having denied them something. What is that something?

I think that something is immortality. Have kids, and your genes live on after you. Fail to have kids, and you are a Darwinian dead end.

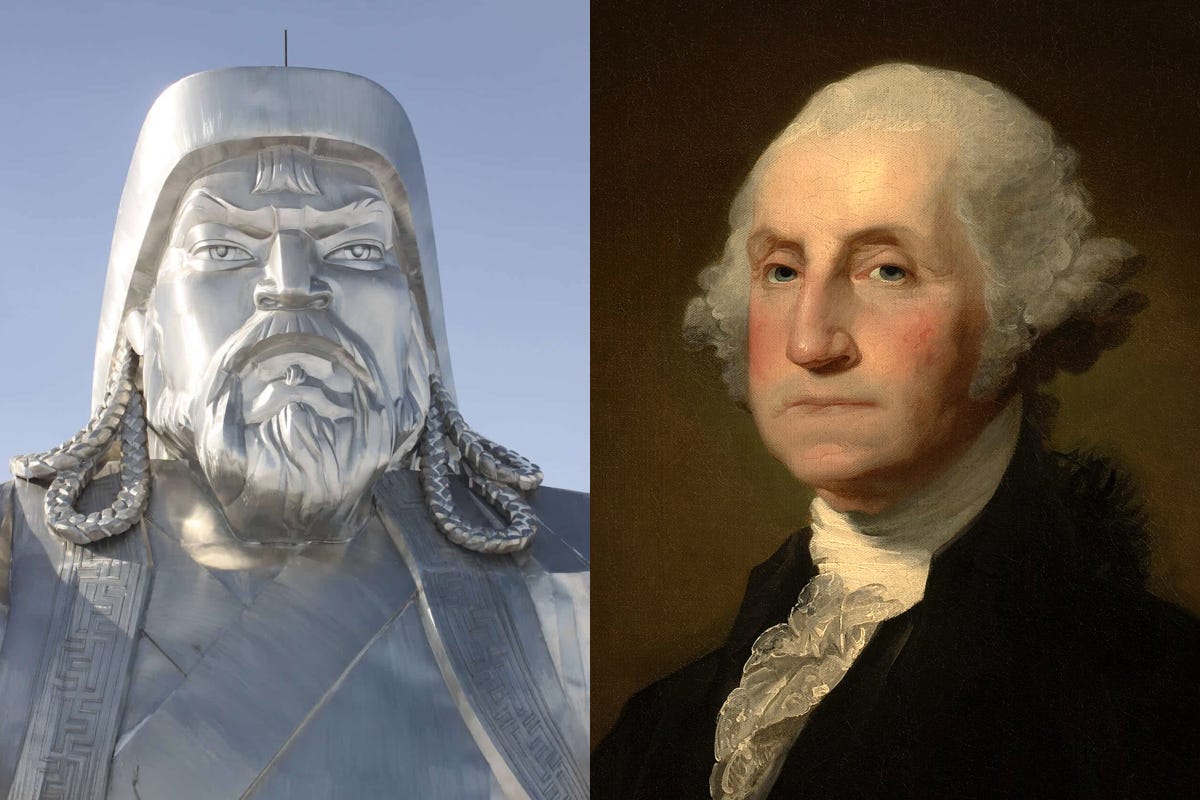

If you use that as life’s measure (and our internet-dwelling wanna-be steppe lords probably do), the most accomplished man in recorded history was probably Genghis Khan, from whom purportedly one out of every 200 people alive today can trace their lineal descent. In his case, that genetic legacy is clearly related to the phenomenal political achievement of his lifetime for which he is remembered: uniting the Mongol tribes into a single, formidable military force that conquered the largest land empire in human history. But you don’t have to conquer the world to leave a lasting genetic footprint: a number of other mostly-anonymous men have had a comparable genetic impact on at least a fraction of the globe’s human population. Founder effects can be incredibly powerful; a small, inbred group may later experience dramatic expansion and dispersion, and as a result a virtually unknown Irish warlord from the Dark Ages has three million lineal descendants today.

What does that mean though? Our selfish genes may desperately want to propagate themselves, but why should we adopt their perspective? To the ancients, continuity across the generations wasn’t about genes (they didn’t know about them) but about one’s name. A hero might achieve immortality through his great deeds, but for a normal person the important thing was to have legitimate children who would keep the progenitor’s name alive and his property intact. On that score, Niall of the Nine Hostages hasn’t done that much better than the rest of us.

Nonetheless: we may not be able to conquer much of the known world, as Genghis Khan did, but the idea of this kind of vicarious immortality on a vastly smaller scale can still have a primal draw. We can’t all be emperors of the known world, but can’t we be emperors of our own little worlds, with children and grandchildren to carry on our names therein?

We can try. But how will our names be remembered if we do? Well, how is Genghis Khan’s?

The Mongols are remembered, by those whom they conquered, primarily for destruction—but perhaps we don’t give them their proper due. There’s a case to be made that the Mongol Empire did have a substantial positive impact on the world, and not just the familiar negative one of sacking cities and wrecking civilizations. They shaped much of the subsequent history and culture of vast swathes of Eurasia and even beyond. If nothing else, they established new patterns of trade across that vast landmass and thereby facilitated the technological and economic development of both Europe and East Asia.

But even in positive terms, did they leave a legacy or did they just have an impact? Unlike Muhammad and his successors, Genghis Khan neither founded and spread a new religion nor (like Constantine for Roman Catholicism) anchored one with a formal establishment. The Muslim world is still large and growing; the Mongol world has long since faded into memory. Neither did the Mongols leave a notable political legacy. For over 1500 years, Europeans have dreamt of a new Rome, the inspiration for every European empire on and off the continent, not to mention a core model for Americans when we framed our own constitution. Who, besides the Mongols themselves, looks back to Genghis Khan? Ivan the Terrible may have followed Mongol precedent in establishing his autocracy, but the Russian state’s conscious ideal was Constantinople not Sarai.

Similarly, China’s culture and the organization of its state may have been shaped profoundly by the Yuan dynasty, but the more obvious influence ran the other way, with China’s Mongol rulers becoming increasingly Sinified with time, much as England’s Norman conquerors came to speak English and identify as Anglo-Saxon or even British more than they imposed French (or Viking!) culture on Arthur’s kingdom. To the extent that China looks backward today for inspiration, it is still the Qin and the Han that exert the most powerful pull. The Mongols shaped history profoundly, but their cultural and political legacy is as diffuse as their genetic one.

Why am I going on about the Mongols and their legacy? Because I have the sense that the steppe lord fantasists imagine that they are pursuing something grander than just money or status like the greasy-pole-climbing meritocrats whom they resent, and I’m not convinced they are. I think the fact that we don’t look back on the Mongol Empire as an example to emulate says something meaningful. Moreover, the Mongols, having lost their empire, still have what is truly best in life. The open steppe, free thoughts, falcons at your wrists and the wind in your hair: these are genuine goods, and not easily won or held, whereas to crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and hear the lamentation of their women is an experience readily available in vicarious form, on line more than anywhere, and not worth much at all.

But I’m going on about it because I want to contrast Genghis Khan with the father of our own continental empire, a man who looms no less large in our memory than Genghis Khan does in theirs, and whose legacy is arguably even greater, but who bears little obvious resemblance to the steppe lord.

George Washington, like Kamala Harris, did experience many of the joys and troubles of parenthood, because he took an active interest in his stepchildren and step-grandchildren. But his genetic legacy, like hers, is null; he has no lineal descendants at all. He and his wife Martha had no children, which, given that she had already had four by her first husband when she married George at the age of twenty-seven, suggests that Washington might have been sterile. (This is one reason why the suggestion that he had illegitimate children with a Black slave named Venus owned by his half-brother has long met with skepticism despite that family’s tradition holding him to be their progenitor.)

What about his deeds of fame? As the head of the continental army, Washington achieved few military victories and made no great conquests. His primary achievement was simply surviving and holding the army together, outlasting his opponents until a single notable victory at Yorktown made manifest to the British the impossibility of victory at any reasonable price. When the war ended, he retired to Mount Vernon to farm and rest on his laurels.

Oh come on, you say, that’s not the end of Washington’s story. What about his political legacy? When newly independent states foundered under the Articles of Confederation, key leaders, Washington among them, convened to draft a new constitution. But while he presided over the effort, Washington was not nearly as central as Madison or Hamilton in shaping the constitution’s overall design, nor did he negotiate the various compromises necessary to win the support of both Northern and Southern states on the one hand and both small and large states on the other hand. Reflective of his unique stature, the presidency created by the constitution was designed with Washington in mind—yet, as president, Washington’s most consequential act was arguably his decision to retire to private life after two terms in office. That firmly distinguished the office not only from Britain’s Georgian monarchy but also from Caesar’s perpetual elected dictatorship.

It is possible, in other words, to describe Washington’s life in such a way that it sounds like he achieved nothing terribly consequential at all, certainly not through sheer force of will or ferocity of ambition. Yet though he so little resembled either Caesar or the Roman Emperor’s many subsequent emulators from Charlemagne to Napoleon (to say nothing of Genghis Khan), in his lifetime Washington was widely viewed as the indispensable man and the true (though fictive) father of his country.

And those who saw him that way may well have been right. It’s not hard to construct alternate histories of North America that work out quite differently, with no United States of America emerging at all if Washington were not around, only a patchwork of petty states that were easily conquered or manipulated by the still-powerful European empires. Even if such counterfactuals are less plausible than they seem to me, I feel confident in saying that just as Caesar’s name will be remembered as long as Rome’s is, Washington’s name will be remembered as long as America’s. And whatever happens to America and the world in the next decades and centuries, it’s hard to dispute the incredibly profound impact this country has already had on the history of the world. Even if we fall as spectacularly as Rome did, much of the world will be living the physical and ideological ruins we leave behind for generations to come.

My point is not to say that George Washington was great while Genghis Khan wasn’t; obviously Genghis Khan was great if greatness means anything. Rather, my point is that by the standards that take the Mongol conqueror as the exemplar of greatness, and therefore the paragon both of immortal fame and of enduring legacy, it’s not obvious that Washington should be considered great at all. And yet he obviously was; indeed one could argue that he was the greater of the two men, with the more substantial legacy. Recognizing that should incline us to reexamine those standards rather than to doubt the reality of greatness or the importance of a legacy.

And that, I think, is the additional rejoinder I would make to Vance. Looming behind the resentful misogyny that Vance was tapping into, I see Genghis Khan’s shadow, and I see it eclipsing Washington’s as a model for what greatness inherently is, with all sorts of implications for relations between men and women and the plausibility of small-r republican government. We can push back moralistically and say that it’s appalling to think that way, but the people who think that way likely already don’t find goodness sufficiently compelling as compared to greatness, and may well see moral hectoring as little more than a mask for someone else’s ambition and lust for power. (That’s almost certainly how they would see any high-minded defense of Vice President Harris by her stans.)

If there’s a hunger for greatness, experienced personally or vicariously, then I think we need to feed it with a more balanced diet. Washington sired no children. His primary virtues were not audacity and dominance but prudence and dignity. And he was great—as great as they come. I’m not trying to turn him into a plaster saint; I am fully aware of Washington’s own failings. They don’t disqualify him from being called great, any more than his childlessness does.

Few of us are going to be Washingtons any more than we are going to be Genghis Khans. But his example is also available for us in our own small spheres. And following him is a much better bet if you want to be remembered well than fantasizing yourself a lord of your own little patch of steppe.

Catholics in particular have to include forms of fruitfulness that don’t involve biological children in what it means to lead a full and flourishing life. Cloistered, celibate religious lay down their lives for the sake of a deep relationship with God and interceding for the world.

Children are a sign of living generously, making one’s life a gift to others. And a culture with declining marriage and fertility raises questions about how we’re preparing to see our lives as not only our own. But it’s not fair or accurate to tag any particular person without children as selfish or disconnected from the future.

FWIW, Akhil Amar recently argued in his constitutional history ("The Words That Made Us") that George Washington was more significant than both Hamilton and Madison in the motivating the structure of the Constitution and should properly be seen as the father of the constitution.. He argues that Madison's influence is overrated, shown by the fact that he lost on almost all of the distinctive thins he argued for. And while Hamilton was important, Amar argues that he was a catspaw of sorts for Washington, putting forward a geostrategic vision of strong state necessary for America to be successful, a vision for which Washington was viewed as the primary proponent. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/context-and-consequences-on-akhil-reed-amars-the-words-that-made-us/