Can You Commit Genocide In Self-Defense?

A question intended to provoke discussion, not outrage

I teed this post up before I went on vacation (I’m still on vacation), thinking at the time that it was probably a bad idea because the title was obviously provocative, so I should probably be around and engaged if people are actually provoked by it. Now I’m fretting that it was a mistake because events are moving so rapidly and ominously that this take already feels outdated. I’ve taken a look to make sure that the piece still works, and I think it does, but the main thing is: I meant what I said in the subhed, in that I hoped to provoke discussion, not outrage. I hope it still can.

Earlier this month, The New York Times published a piece by Omer Bartov, a professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown University who is of Israeli origin, declaring that he has come to the painful conclusion that what Israel is doing in Gaza does, in fact, meet the definition of genocide. This follows multiple other Israeli figures, such as former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, declaring that Israel is committing war crimes, and has been followed by the escalation of hunger in Gaza to the point of starvation, a situation which is clearly Israel’s responsibility and which is turning even some previously ardent defenders of the Gaza war against the current government’s prosecution thereof. But neither Olmert nor these other recent critics have crossed the line to using Bartov’s loaded term. Why not?

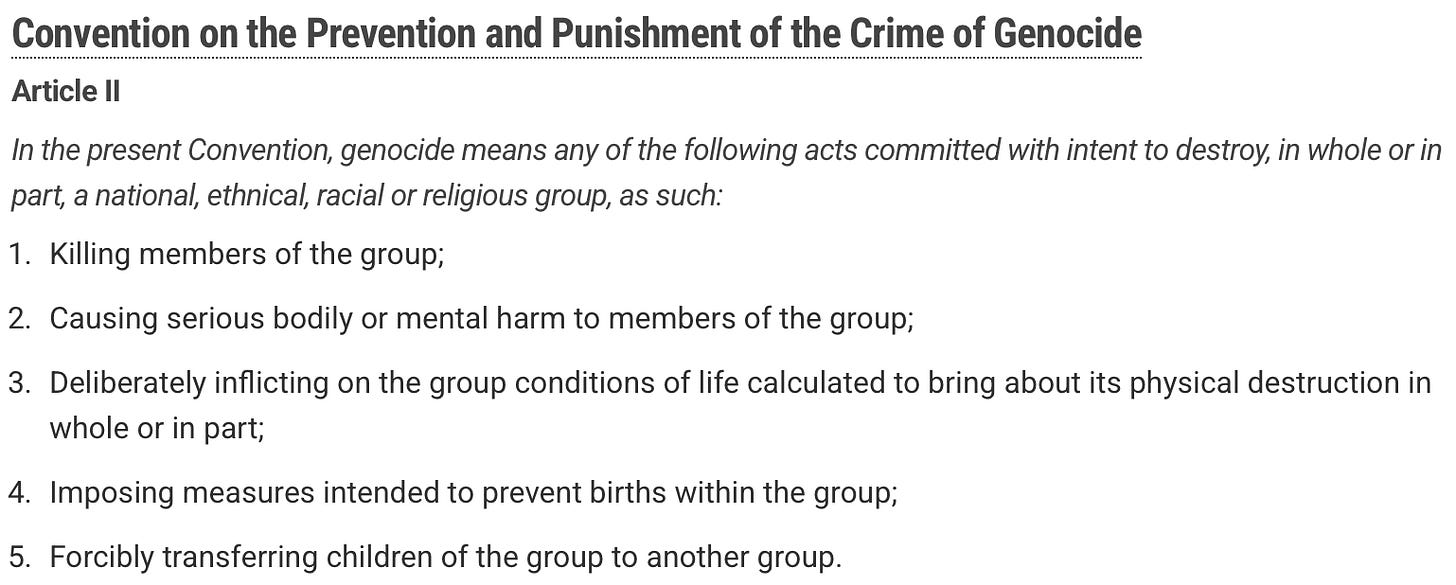

The definition Bartov is using comes from the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which was subsequently used in other treaties as well:

The heart of the matter, what distinguishes genocide from other war crimes or from other kinds of carnage that may not be criminal at all, is the intent to destroy a group. If that intent has been established, then a variety of possible actions—not only deliberate mass killings but creating unlivable conditions, kidnapping children, etc.—that might be criminal in their own right regardless of genocidal intent (or, in some cases, might not), rise to the level of genocidal when undertaken under the ambit of that larger intent.

That, in turn, is the reason given by so many—both those who were highly critical of Israel earlier in the war and those who have only turned against it more recently—for refusing the loaded term “genocide.” Israel’s war aim, they aver, is not to destroy the Palestinian people, in whole or in part, but to destroy Hamas, a terrorist group and a political entity that has itself expressed explicitly genocidal intent, and put that intent into practice on October 7th, 2023. All the horror that has been visited on the people of Gaza since—including the burgeoning crisis of mass hunger—is not only a consequence of that attack but of Hamas’s subsequent refusal to give up on the war they started, lay down their arms, and flee the region. If the destruction of Gaza is a genocide, then Hamas is the entity with genocidal intent not only towards Israel’s Jews but toward the Palestinians they claim to represent since, by their actions, Hamas has demonstrated an intent to sacrifice their own people on the altar of their national and religious ambitions. (And, to the extent that the people of Gaza still genuinely support that choice, we’re looking not at genocide but at national mass suicide.) But Israel’s intent isn’t to destroy the Palestinian people; it’s merely to defend itself.

This is the argument. I’m not honestly sure how you establish intent with sufficient clarity except in circumstances where the alleged criminals have already been removed from power and their records are open for examination by their conquerors or successors, but that’s a problem for the ICJ, not for a commentator like myself. In fact there are ideological extremists in Israel’s government who have repeatedly said that Gaza should be depopulated, and there are also individual soldiers and units and commanders who hold similar views and who have taken actions that look an awful lot like they are intended to make Gaza unlivable as such, and who have not been disciplined for such. But Israel’s defenders argue that these kinds of statements and actions are not directed by those responsible for government policy, and therefore aren’t expressions of the government’s intent. Moreover, even if it were proved that this government was culpable at the highest level, you could still separate its views and actions from those of the Israeli people in general if the government was acting against the people’s demonstrable wishes and beliefs—which would be very useful for articulating a post-Netanyahu path forward that blamed this government for horrible crimes, but exonerated the Israeli people as a whole.

Suppose I grant, for the sake of argument, that the deliberate intent to destroy the Palestinian people as a positive goal is not driving Israeli policy nor is the aim of the bulk of the Israeli people. Is that enough to exonerate Israel of Bartov’s charge?

I’m not sure it is. To explain why, I have to raise the question in the title of this post.

Intent figures in criminal law all the time. If you kill someone unlawfully with intent to do so, for example, that’s murder; if you do it without malice aforethought, that’s manslaughter; and if it’s entirely unintentional but is your responsibility, that’s negligent homicide. All of that tracks reasonably well with the debate about possible genocide in Gaza; perhaps what is happening now in Gaza is wrong, but if so it is negligent homicide rather than murder.

But you can also kill someone with intent but with a justification other than malice that results in the homicide not being a crime at all. Self-defense is the paradigmatic example: if you reasonably believe someone is actively about to do you harm, especially potentially fatal harm, you may well be justified in using deadly force to prevent them from doing so. And that tracks better, it seems to me, with what Israel’s defenders actually think is going on in Gaza. It’s not that the destruction was an unanticipated and unintended side-effect of war—most of it was fully anticipated, and much of it was undertaken deliberately. But it was done under the ambit of self-defense.

Surely, though, there’s a difference between legitimate actions undertaken for self-defense and war crimes committed with self-defense as a mere excuse. If what Israel is doing has nothing to do with actually defending the country, then it is simply guilty. If much of what it has been doing is legitimately related to self-defense, then it is simply not-guilty. Right?

Maybe. But what if self-defense cannot be achieved without destroying Gaza utterly? Would that mean that the destruction of Gaza wasn’t genocide? That doesn’t seem right—the destruction happened, and if it gets even worse then what are we going to call it? So does that mean that genocide was justified on the grounds of self-defense, as self-defense can justify homicide?

That might sound like an absurd idea, but before saying so, consider the narrative that your average middle-of-the-road Israeli or Israel-defender feels in their bones. Not a Greater Israel ideologue nor a two-state-believing liberal Zionist, just your paradigmatic Iraqi Jewish grocer or second-generation graduate of Camp Ramah. This is an imaginary person (more than one type of imaginary person that I am conflating here), so I’m obviously making this up rather than reporting a specific person’s beliefs. But this is the narrative that I think such a person would believe.

In the early 1990s, Israel and the PLO entered into a historic peace agreement: the Oslo Accords. A negotiated process was to replace violence as the means of settling the conflict, at the end of which borders would be agreed upon between sovereign Israel and a Palestinian entity (perhaps even a full-fledged state), and both peoples would have peace, security and self-government. After seven years, an Israeli government was ready to sign a final status agreement that would have granted a Palestinian government substantial sovereignty, even over part of Jerusalem. But what happened? This offer was met with a campaign of suicide bombing against civilian targets all over Israel.

So Israel responded by taking unilateral action to achieve its own security. Israel walled off the areas of the West Bank where Palestinians lived from Israel proper, and from areas within the West Bank where the bulk of Israeli settlers lived. At the same time Israel withdrew entirely from the Gaza Strip, handing complete control over to the Palestinian Authority, with whom they continued to negotiate about a possible final status agreement, coming fairly close to an agreement in 2008. But what happened? The people of Gaza elected the Islamist terrorist group Hamas to govern them, and Hamas immediately began preparing for war against Israel, digging a huge network of tunnels under their territory, smuggling in weapons and the materials to make them, and repeatedly launching waves of rockets at Israeli civilians.

So Israel got extremely proficient over time at intercepting these rockets, and also responded forcefully to major provocations to deter their recurrence. But they never responded by reoccupying the territory, and over time things settled into a modus vivendi of sorts. There were no formal relations between Israel and the Hamas government, but Gazans could work in Israel and even Hamas itself was mostly left alone if it left Israel alone. Perhaps there wasn’t justice, but that’s because there wasn’t peace—and in the meantime there was quiet. But what happened? On October 7, 2023, Hamas launched a surprise attack on Israel against both military and civilian targets, murdering over a thousand Israelis including infants and the elderly in the most brutal and intimate manner and kidnapping hundreds of others, an attack launched with the express though absurd intent of conquering the entire country and driving any Jewish people who they didn’t kill out of their home and into exile.

So Israel finally went back into Gaza in full force. What should they do now that will prevent the next turn from being even worse? How can you deal with a people who behaves this way? Peace with them is impossible. Containment is impossible. Which means living beside them is impossible. But if you can’t live beside them, and you aren’t going anywhere, then . . . don’t they have to go?

I want to stress: the foregoing narrative is not, by any means, an even-handed description of the last thirty-two years. There’s a Palestinian narrative of Israeli crimes and deceptions that I’ve entirely left out, of settlements relentlessly expanded, of Jewish terrorism ignored, of collective punishment inflicted in disregard of Palestinian lives, of Palestinian extremists tacitly supported by Israel while moderates are undermined, and so forth, a narrative that is also one-sided and incomplete and blind to its own side’s crimes and delusions, but with plenty of truth in it as well. But the first narrative I outlined also contains plenty of truth, and that version is what I suspect a lot of not particularly ideological Israelis and Israel’s supporters believe to be basically true. And if you believe that narrative, then haven’t you come to the conclusion that genocide would be justified on the grounds of self-defense, if nothing else would work? Maybe you still don’t want Gaza to be destroyed—maybe what you want is peace and coexistence. But if you can no longer imagine that happening, and therefore can no longer countenance taking any risks for such a goal, then what is going to stop your policy from becoming functionally genocidal at some point? And if nothing stops it from being so, then how is it not so?

The usual rejoinder to this is that both Hamas and the Palestinian people have agency, and that is absolutely correct. But I don’t think that’s the knock-down argument that people who deploy it seem to think it is. Consider an analogy. At the end of World War II, the United States dropped atomic weapons on two Japanese cities, thereby bringing the war to an end without requiring an invasion of the Japanese home islands—an invasion that would have resulted in hundreds of thousands of American casualties and millions of Japanese casualties, at a minimum. Leave aside whether dropping the bomb was justified on those grounds; that’s not where I’m going with this. The reason an invasion wasn’t necessary is that the Japanese surrendered, and the reason the Japanese surrendered is that the Emperor Hirohito was prepared to surrender—provided America allowed him to retain his throne. America was seeking an unconditional surrender, yet we accepted this condition, and the war came to an end.

What, though, if we had not? What if we had said “no, you must surrender without conditions and rely solely on our mercy?” What if, as a consequence, Japan refused to surrender at all? After the atomic bombings, Japanese War Minister General Anami rejected the idea of ever surrendering, saying to the emperor: “Wouldn't it be beautiful for the whole nation to be destroyed like a beautiful flower?” What if Hirohito had agreed? Would America have been justified in bringing that end about, dropping one atomic weapon after another on the Japanese islands until the Japanese people were effectively exterminated, because they, in their madness, refused to unconditionally surrender to an obviously superior force? To answer “yes” seems to me like an obviously repugnant conclusion.

Bartov’s main concerns in his piece are the international legal framework that forbids genocide and the credibility of the scholarly community that he is a part of. The latter question strikes me as very parochial, and I’m happy to leave it to him. I’ve written on the former subject before, in, for example, “Ethnic Cleansing and the Stakes in Gaza” and “Preventing Genocide Is Good,” a pair of pieces that pretty well cover my skepticism of foreign policy moralism and my appreciation nonetheless for the pragmatic value of the idea of liberal internationalism, an idea that was dying from a thousand cuts even before Russia invaded Ukraine or Israel responded to to October 7th massacres by destroying Gaza.

But ethics matter even if there’s no structure to enforce them, even if third parties are never really going to make imposing some universal framework a central pillar of their foreign policy. And psychology matters because few of us do things that we believe are unjustified, so it matters what mechanisms we use to justify our actions to ourselves. Ordinary Israelis not only feel the Gaza war was justified, they feel it is obviously not genocidal in intent. And they have good reasons for believing this beyond their love of their own country and desire to think well of it. Ordinary Israelis are not hungering to resettle Gaza. That’s a fringe position—one with real leverage over this government, but very little popular support. Ordinary Israelis don’t even support continuing the war at this point; they’re tired and they want the hostages back more than anything.

That isn’t the end of the story, though. Are ordinary Israelis interested in figuring out how to live alongside the people of Gaza? I see no evidence that they are at this point, and no evidence that they would reward an opposition that was interested in figuring it out. Indeed, every plausible alternative to the current drift toward an endless cycle of destruction, whatever name you want to give it, is distinctly unpopular: there’s no confidence in the Palestinian Authority, or in the international community, or in any other entity to be able to provide security. Needless to say, there’s certainly no willingness to countenance a return to power by Hamas, however weakened. What ordinary Israelis were thrilled by was Trump’s short-lived “plan” to turn Gaza into an international resort populated by someone other than Palestinians. Why? Because it promised to make the problem of Gaza—which is to say, the people of Gaza—go away.

That’s a normal desire for them to have in the situation they are in—just as, I believe, it’s a perfectly normal desire for ordinary Palestinians to want Israel to simply cease to exist. These aren’t desires that lead to anything but horror, but it’s not hard for me to understand them. But when you have the capacity to make such a desire come true, that strikes me as a door through which genocidal intent really could enter, if it hasn’t already. The justification from self-defense isn’t remotely unique in the annals of genocide, after all.

And this is why I’ve been worried about this government’s determination not to even think about any political endgame from the very beginning of this war—which is horrific enough even if it doesn’t meet the strict definition of this most horrible crime. You can’t separate the despair of political possibility from the question of genocidal intent. Politics is about working out how to live together. War is—or should be—an extension of politics with the addition of other means: you’re using force to change the terms under which you will subsequently live together. Drop that framing, and war becomes the ultimate way of avoiding politics—not a means to but an alternative to working out how to live together. How does a war framed that way end, do you think?

Genocide and ethnic cleansing are lumped together, but I don’t think they’re identical or equally wrong. After a certain number of failed attempts (number and intensity unspecified!) to live alongside each other, I do not think it is per se wrong for Israel to attempt to expand its borders to cover the Palestinians lands and expel the inhabitants and press their ostensible allies to resettle them.

Pressing a people to move is not as bad as genocide, and I think that, though extremely undesirable, it can sometimes be the least bad option.

Gaza is so small that clearing a full demilitarized/buffer zone is essentially an attempt to empty it. It’s different for the Koreas, which are large enough to maintain a space between. Having no place for civilians to flee away from the front makes this war much much worse.

We’d be better off if women and children could go to refugee camps in the Sinai, even if that weakened Palestinian negotiating positions.

On October 11th 2023 an article was published stating that "any significant response from Israel would result in genocide".

So about the time the first response started the propaganda machine of "it's a genocide" had already started.

The fact is the genocide accusation gives Jew haters a great umbrella to hide under after they do their wicked deeds.

We must face the reality that Israel must destroy Hamas, Hezbollah, PIJ et. al. for Israel's long term viability and the survival of the Jewish people.

The fact so many people think this war is "genocide" is beyond absurd. It is the product of propaganda and a general lack of understanding of many factors. In reality, the IDF would prefer not to conduct "urban warfare" but that is not a reality given the proximity, location, and strategy with Hamas. That said, the Allies achieved victory by bringing Germany and Japan to its knees. As we all know, the US dropped not 1, but 2 atomic bombs on Japan, decimating two cities and its inhabitants.

I don't know how this entire conflict ends given how ingrained anti-semitism is within the Islamic world. However, demonstrating to the Palestinian people that their "River to the Sea" (pipe) dream is only going to make their future more and more bleak. They need to be shown (by force if necessary) that the land for a future state will only get smaller, not bigger if they don't end their real genocidal pursuit of eradicating Jews from the middle east"

If people around the globe really cared about the Palestinians, this is the narrative they would push (i.e., settle for what you have now or start thinking about immigrating to other Arab states). This is the only practical real long term solution.

In the mean time a cease fire will NOT help the hostages.

https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/20916/gaza-ceasefire-hostages