As I mentioned in passing once before, when I was in middle school I wrote a play about Emanuel Ringelblum, the historian of the Warsaw Ghetto who painstakingly recorded the lives and deaths of his fellow residents there, the long torturous tale of the community’s deliberate extermination by the Nazis. My choice of subject was telling, I think, but what it told was that I could imagine being Ringelblum, a historian and a writer, better than I could imagine being Hannah Szenes or Janusz Korczak or whomever else one might choose to make a hero from that terrible period in history whose fundamentally anti-heroic character Primo Levi described so well in If This Is a Man. And, necessarily, my play contained stirring language about the importance of that work, how vital it was that the people of the future know what truly happened.

The injunction “never forget” had become a commonplace long before I was in middle school, but as I re-read my play, I see that even then I didn’t particularly believe the pious liberal understanding of that command. My Ringelblum didn’t want the truth to be known so that nobody would ever allow such a thing to happen to anyone. He wanted the truth to be known so that Jews would never allow such a thing to happen again to us.

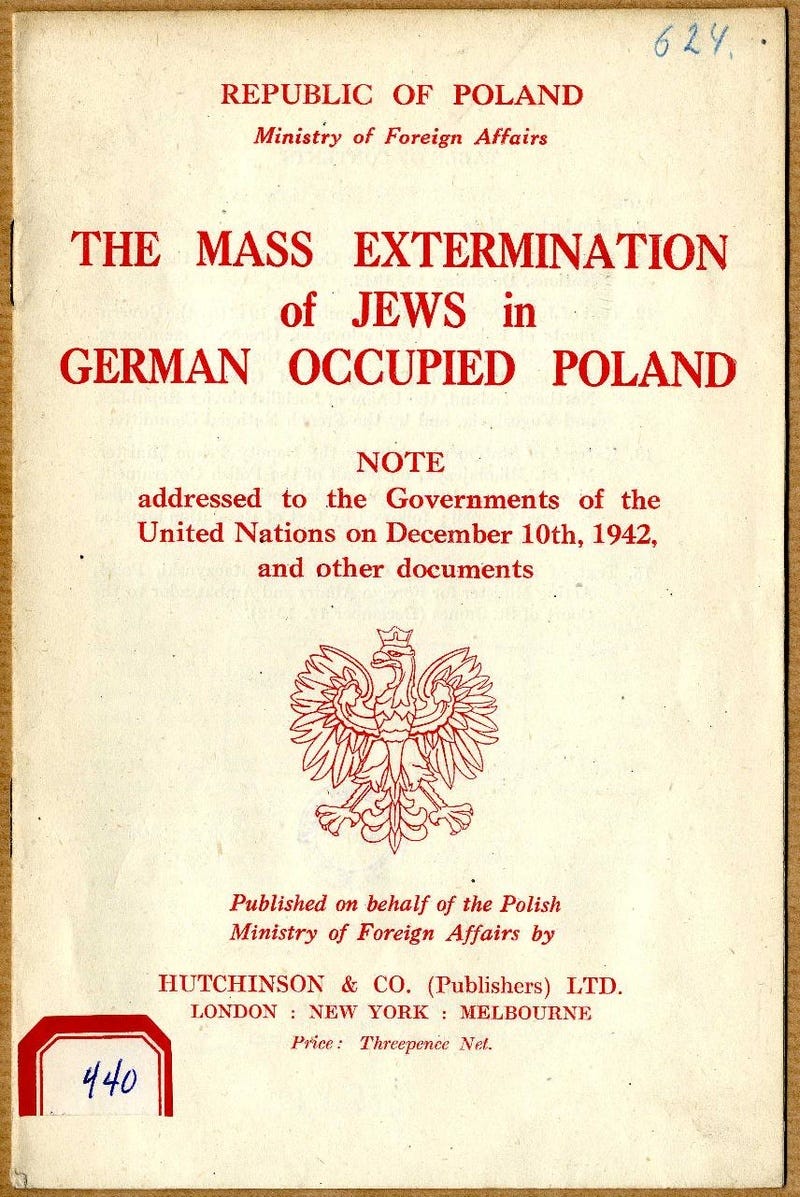

I thought about that today as I attended the last performance of Remember This: the Lesson of Jan Karski at Brooklyn’s Theatre for a New Audience. The one-man show, performed by David Strathairn, is a tour de force. It’s storytelling theater rather than drama, but Strathairn is a fabulous storyteller, and the story he tells is riveting, recounting Karski’s efforts as a courier to bring news from the Polish resistance to their government in exile in London. The Karski who emerges from the story is a warm, self-effacing, fundamentally decent man, the picture of someone who became a hero not out of ego but because he was too conscientious to be anything else under the circumstances. To my mind the most appealing thing about him as portrayed in this play is that he doesn’t seem to have acted out of any particularly sophisticated political or ideological motives. He was a simple Polish patriot and a good person, and he tried to do his job well. That job was to observe, and to report what he observed. What people did with those observations was their responsibility.

So what did they do with them? The play doesn’t detail what the Polish government in exile or its allies did with information Karski brought out about the condition of the Polish resistance, or about its fractiousness. That, though, was what they most wanted to hear: information that would be relevant to the resistance’s ability to aid the allied war effort, as well as information that would be relevant to the post-war situation in Poland. The ongoing extermination of the Jews, by contrast, was something already known to them, reported multiple times, and pressed upon them repeatedly by the representative of Polish Jews in London, as well as by the Polish government in exile. What they did about it—nothing much during the war, though the revelations of the Holocaust did have a material impact on post-war policies toward refugee populations—is also a well-known and often-told story. The play feels like it wants to be received as news, but what news is it bringing?

To some extent, its answer might be: you, Noah, know these things, but plenty of other people don’t. I noted the audible gasp from the audience when Karski meets with Felix Frankfurter, the Jewish Supreme Court Justice, and tells him what he saw with his own eyes in the Warsaw Ghetto and in a Nazi death camp, and Frankfurter flatly tells Karski he doesn’t believe him. I assume the audience couldn’t believe that a Jew would react that way to a story about the mass murder of Jews, as if the only reason why the story would be disbelieved was prejudice. But the reason Frankfurter doesn’t believe him, he says, is that his stories were simply too horrible to be believed. Frankfurter can’t accept that human beings, en masse, would do such terrible things. Given our predisposition to think well of each other, the reminder that yes, human beings have done such terrible things, and they will again, is worth re-learning.

But what follows from this? That’s the real question, isn’t it? Karski’s refrain, throughout the play, is that governments have no souls; only individuals have souls. People can be moved to do good, or to do evil—or they can fail to be moved, and be indifferent. Governments, though, think only about their interests, and feel nothing. I take that to be the lesson he learned from the experience of government inaction in the face of the information he brought, but of course he wasn’t just ignored and disbelieved by governments. He was also dismissed by individuals, including individuals who were not enmeshed in the institutions of government. And they didn’t just disbelieve because Karski’s reports, like those that had come before, were too horrible to credit. They also disbelieved because belief would have necessitated doing something. As Strathairn’s Karski admits, those who didn’t know didn’t want to know.

So I left the theater feeling rather like I did in middle school about Ringelblum. No amount of information or education is enough. Strangers may be kind or they may be cruel, but depending on the kindness of strangers is not a strategy. The only answer to the dangers of powerlessness is power, and the only answer to Auschwitz is Dimona.

And yet, once that is conceded, Karski’s refrain echoes in a different way. If governments have no souls, then putting trust in a government—even in a government erected specifically for the purpose of empowering a group who had experienced the worst consequences of lacking that kind of power—is putting trust in something soulless, inherently indifferent to moral appeals. Once you have power, you have the obligation to exercise it responsibly and morally. But those are matters of soul, and soul is precisely what government doesn’t have.

The China Syndrome

I intend to write more extensively about the Biden Administration’s dramatic moves to try to hobble the development of China’s advanced semiconductor industry and related industries like artificial intelligence. The one thing that is clear to everyone, though, is that a rubicon has been crossed that cannot easily be crossed back. This is not just a decoupling, but virtually a declaration of economic war.

It feels very strange, in that context, that only a week ago I was writing, in my first piece for Persuasion, about the dream of a friendly and liberal China that dominated American hopes during the 1990s and 2000s, and why they didn’t come to pass. I talk about why the waves of democratization during the 1980s and 1990s gave us reason for optimism about China’s ultimate political trajectory, why the CCP’s interests always militated against liberalization, and how technology and other factors would up helping the regime retain control as much or more than they helped empower ordinary citizens. But then I argue the following:

[T]he mere fact that the United States was championing democracy and liberalism meant that those political ideals came to be identified with American leadership. That was probably helpful in expanding liberal democracy in Eastern Europe in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union, when those countries were eager to join the West culturally and economically, and to find shelter under the American nuclear umbrella. But the same was not true for countries that had historical reasons to hold America at a certain distance, to say nothing of rival great powers like Russia or China. Insofar as liberalization was promoted as a mechanism for integration into an American-led system, it was bound to be treated with skepticism at best.

The sheer scale of China’s potential power, moreover, made it especially unrealistic that the country would accept a spot as America’s junior partner. At the beginning of the century, China’s population was over four times greater than America’s. As China became a middle-income country, its economic clout would approach and eventually surpass America’s, and its military capacity would inevitably follow. Why would such a powerful country ever be satisfied with an American-led global order? And if they would not, why would we assume they would willingly bring their political system into line with our own?

This isn’t exactly warmed-over Sam Huntington; I’m not arguing that there’s anything distinctive about Chinese civilization that is incompatible with liberal democracy (tell that to the people on Taiwan). Rather, I’m making a more banal point: China sees itself as a great power, and over the past 20 years it has achieved the kind of power that validates that conception. That is the fundamental fact that America has struggled to reckon with. We didn’t reckon with it back when China was patiently building up power while trying to avoid rocking the boat. Now we’re dealing with it in the context of a Chinese regime that is more dangerous, more hostile, and more impatient. And for very understandable and valid reasons, we’re dealing with it in a way that is virtually guaranteed to deepen both that hostility and that impatience, and hence that danger. Decoupling looked likely to be wrenching enough; this is a whole other level.

Anyway, read the whole thing.

On Here

Two posts on this site since my last wrap:

First, after Yom Kippur, a meditation on what faith means in a Jewish context, whether I have it, and if I don’t, what I’m actually doing when praying on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar.

Second, yet another piece about the nuclear danger in Ukraine, this one asking whether we’ve actually got defined war aims there, or whether we’re opportunistically trying to weaken Russia as much as possible, and what either stance means for the prospects of a negotiated end to the war (hypothetical for now since Russia has shown no signs of being interested in serious negotiations).

The Season of our Joy is almost over. Oh, goody. I can’t wait to see what comes next.

Noah,

I agree with everything you wrote, but in the current political climate (in America and around the world) the Politics of Resentment now extends far beyond the Jews alone.

There is an aggrieved majority who feel left behind, left out, and betrayed. And demagogic leaders skillfully leverage that frustration and anger and resentment to their own ends, always pointing the finger at scapegoats: “They,” the demagogue tells his followers, are to blame for your discontent, “they” are taking over your country, “they” are replacing you.

Early in his career Hitler stirred up crowds with the claim that “they stabbed us in the back.” When asked who exactly were “they,” he said it didn’t matter; people could project any enemy onto that word. The basic key was this: “they” are not like us.

Perennially, of course, “they” were the Jews. Long ago Nietzsche called anti-semitism the “ideology of those who feel cheated,” and here in our modern year of 2017 the world witnessed hundreds of tiki-torch-carrying angry white males winding their way like an evil snake through the University of Charlottesville campus chanting “Jews will not replace us.” (White males especially feel themselves under attack by wide-ranging demographic, economic, and societal changes.)

But in today’s neo-fascist world “they” now take many forms: Muslims, Mexicans, immigrants, globalists (especially, of course, international Jewish bankers like George Soros), socialists, liberals (with their “radical” liberal agenda), elites, intellectuals, LGBQ folks and blacks and all those “others" who seem to get special privileges. In the politics of resentment, “they” are the problem, and neo-fascism is the solution.

Madeleine Albright in her 2018 book Fascism: A Warning, said that "in the end, it is always about giving them someone to hate." Jews took the brunt of this paranoid hatred for millennia, but now (with Jewish voters a very important voting block in the US) "they" have many new faces and names. Now George Soros and Liz Cheney are somehow linked together as the dangerous "others."

Mostly I am reminded by W.B.Yeats's terrifying image in The Second Coming: "and what rough beast slouches toward Bethlehem to be born."

All we have are our votes and our voices in a battle we must not lose.

I have also added my voice at Neo-Fascism: A Warning. I hope you find something of value there. No matter what the results of Nov. 8, I will continue with this project.

https://neofascism.substack.com/