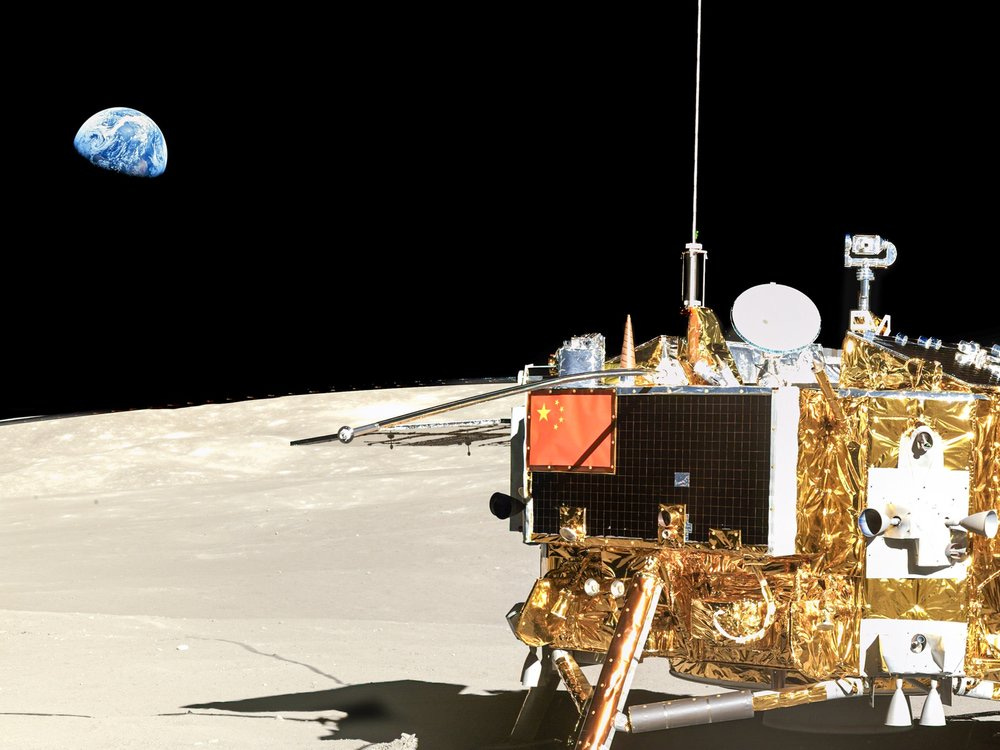

Chang'e 4 lander on the Moon, by CSNA/Siyu Zhang/Kevin M. Gill - ChangE-4 - PCAM. The image is actually from the far side of the Moon, from which the earth is, obviously, not visible, but I’ve added the earth anyway for purely aesthetic reasons.

Among my other accomplishments of the first quarter of this year, I finished a draft of a new screenplay that, in a departure for me, is a science fiction thriller. I hadn't really ever written a script before that was solidly in a genre; my feature that I directed, “Resentment,” is a drama, and my other scripts are either dramas or genre hybrids of one sort or another. I had an idea that I thought might work, and I wanted to see if I could execute.

In the process, I came face to face with the problem that Noah Smith ably describes in this post: the future is increasingly hard to imagine because it is arriving too quickly.

My script is set a few decades from now in a Chinese colony on the Moon, and revolves around a threatened incident of nuclear terrorism. Imagining the future geopolitics that led to my scenario wasn’t particularly hard for me, as you might imagine, nor was coming up with the backstories of the various key characters. I’ve never been a particularly plot-centric writer, but that’s part of why I wanted to write something like this: I wanted to exercise a mental muscle that wasn’t as strong as those that handle theme or character. I think I did a credible job on that front too. But imagining the technological landscape of the future and how that landscape would shape society—arguably the central purpose of science fiction as a genre—was much, much tougher.

The key reason why is artificial intelligence. This is a technology that is here now, is advancing extremely rapidly, but has only just begun to transform society. Fine: you might have said the same in their early days about the printing press, the steam engine, the electric light bulb or the automobile. But none of these transformative technologies promised—or threatened—the possibility of human obsolescence, which is a staple of speculation about artificial intelligence. That possibility, it seems to me, destroys the possibility of writing a story—or, perhaps, the only story one could really tell is the story of the obsolescence of humanity itself. The Antiquities, a play I saw earlier this year, tried to do that, and frankly it was just really depressing without being all that engaging as a story.

Now, we don’t actually know that artificial intelligence is going to render humanity obsolete. I’d bet against it personally. But if you are betting against it, then you have to not only imagine the possibilities of the technology, but take a strong view of its limitations. That is, to say the least, not a common tack taken by science fiction writers. Plenty of hard science fiction pays close attention to the limitations imposed by physics, but in so doing it didn’t need to push back against a background hype suggesting that, say, faster-than-light travel was just around the corner. And because artificial intelligence is advancing so rapidly right now, if you imagine any specific limitations that allow you to start imagining the structure of a future society, you’re overwhelmingly likely to get those specifics wrong—and you may well get them wrong in ways that will be obvious before you finish writing. That’s . . . not ideal.

For some kinds of stories this may not matter. In Maybe Happy Ending, the wonderful musical currently running on Broadway that just got nominated for 10 Tony Awards (and which I wrote about in the latest issue of Modern Age), the two retired robots that are the focus of the story drive to Jeju Island, and there’s discussion about whether robots are allowed to drive. They stop at a sex hotel along the way, and there’s a humorous scene where they attempt to be human so as to fool the hotel manager. Now, if we have humanoid robots that can drive cars, then clearly we also have self-driving cars. We also probably don’t have hotel managers anymore. And chatbots are already good enough at pretending to be human that they’d be unlikely to make the kinds of (very funny and clever) mistakes that the robots make in that show. None of that matters, though, because the story is only about technology inasmuch as it’s about certain philosophical questions that the technology throws up. But for a plot-driven story like the one I was writing, in which the specific capabilities of this or that technology are crucial, I don’t think that kind of hand-waving is adequate.

I think I solved the problems well enough, which is to say: I think I gestured toward what this future society might be like in ways that don’t feel gratingly false without having to draw hard and sharp lines around what artificial intelligence can and can’t do. It clearly hit some kind of plateau and never developed into super-intelligence, and it’s clearly been integrated into the machinery of the surveillance state in ways that make that state very powerful, and it’s clearly transformed the nature of work. Some of what I’ve got in there feels less like a set of predictions and more like a set of comments on the way we already live—and some of it already feels like retro-futurism. (It’s really un-cinematic to assume that people at work in the future will talk only to bots and rarely if ever to each other.) I’m frankly also engaged more by some of the philosophical questions than by the technologies themselves, so alongside a fairly limited version of artificial intelligence I posit a couple of curveball technologies more for the purpose of making philosophical points than because I think they’re likely to develop. (In fact, they may not even be possible.)

But I’m not sure. I really do worry that by the time somebody reads the script, it’ll already read like something obviously out of date.

Ultimately it probably doesn’t matter; if the human story is compelling, then even technologically-savvy readers or viewers will probably forgive a bunch of bone-headed tech mistakes. If telling a human story requires those bone-headed tech mistakes, though, that should worry us. I worry about it already. I remember seeing Bo Burham’s film Eighth Grade several years ago, and thinking: is this horrifying dystopia almost entirely bereft of human interaction what children today are actually living in? Apparently so. The script of my own feature film, Resentment—premiering soon; watch this space for an announcement—has a number of key emotional moments that turn on the use of a cell phone. Nonetheless, when one of my department heads first read it, her first comment was how much she appreciated my imagining a world in which phones practically didn’t exist. Why? Because the whole film is people talking to each other in a bar, something that, in her experience, people mostly don’t do anymore.

We write out of our experience. So it says something that, as I point out in that Modern Age essay linked above, increasingly the point of audience identification in our stories involving robots is the robot. The most recent of these was Companion, which wasn’t bad, but was yet another story in which the robots aren’t just smarter or stronger than we are but more human, and in which the humans are either pathetic, despicable or NPCs. I don’t want to write stories like that. But we all have to write stories out of our own experience, out of life as we feel ourselves and those around us living it. If that means an endless parade of more or less speculative dystopias, then that’s what we must think not only about the future but about the present.

How many stories can we tell about how (to paraphrase America Ferrera’s character in Barbie) it is literally impossible to be a human being before we decide to live differently so that it . . . isn’t?