Will Redistricting Favor the Democrats?

On a relative basis, the latest evidence suggests: maybe!

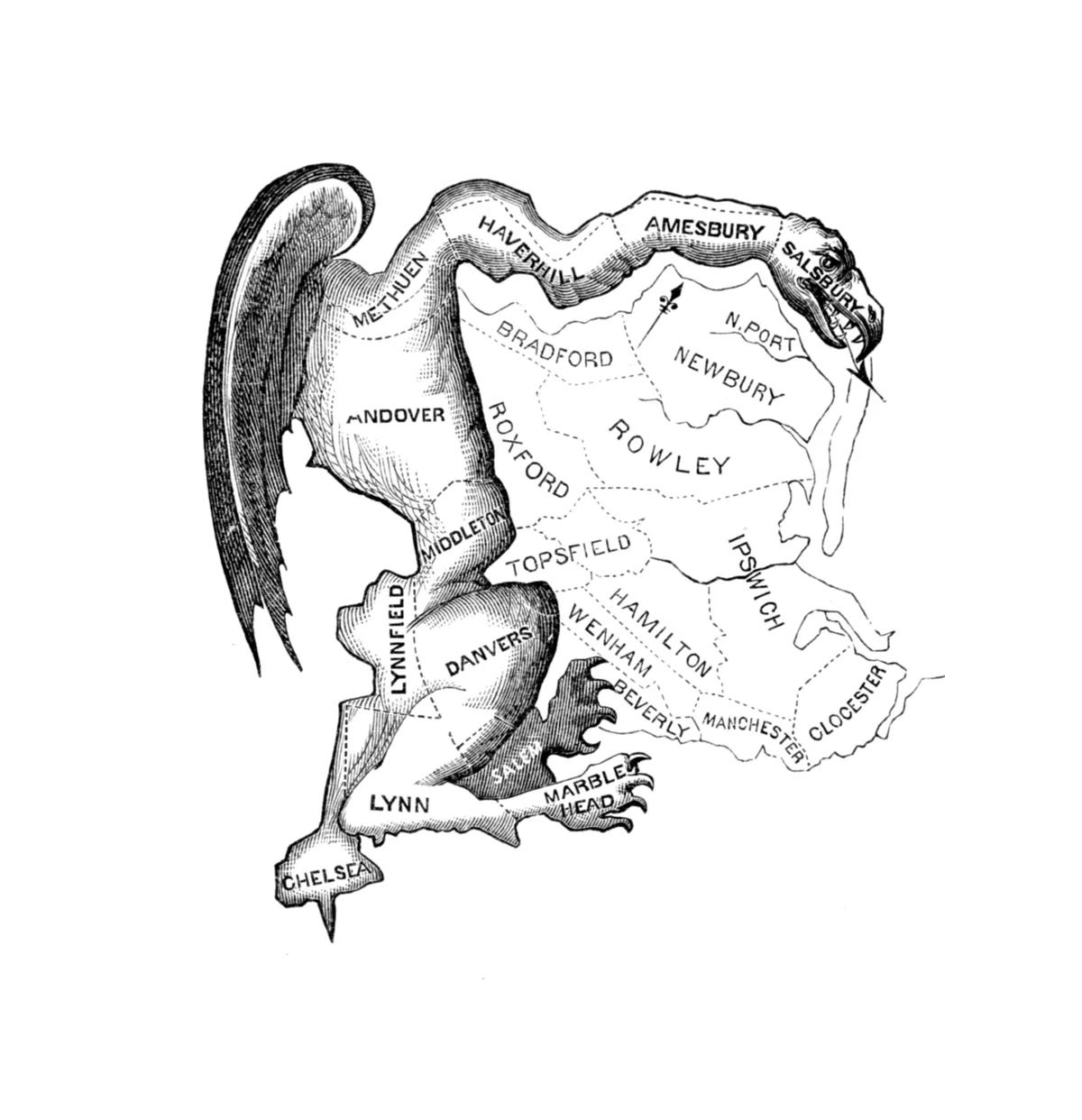

If you write about gerrymandering, you are legally required to post this image

The Cook Political Report has come out with a new . . . report, about the impact of redistricting on the 2022 elections. And the headline is going to surprise some liberals who have been wailing about the pernicious effects of gerrymandering since 2010:

[I]n the completed states, Biden would have carried 161 of 293 districts over Donald Trump in 2020, an uptick from 157 of 292 districts in those states under the current lines (nationwide, Biden carried 224 of 435 seats). And if Democrats were to aggressively gerrymander New York or courts strike down GOP-drawn maps in North Carolina and/or Ohio, the outlook would get even better for Democrats.

That’s a far cry from the disaster Democrats have been fearing. How could this be?

The answer has multiple facets. In the largest Republican-controlled state—Texas—the GOP has grown increasingly anxious about losing their majority. So they drew their new maps primarily with a view to shoring up their own incumbents rather than trying to expand the potential size of their delegation. Some Republican-controlled states, like Michigan, have maps drawn by independent commissions; others are already so heavily gerrymandered that there’s not much more juice to be squeezed from the rinds. Democrats, meanwhile, gerrymandered aggressively in states like Illinois, and got reasonably favorable maps from independent commissions in states like California. The bottom line, though, is that the 2022 map looks likely to be slightly more favorable to the Democrats than the 2020 map.

That’s still a preliminary finding; we still don’t know what will happen in Republican Florida or Democratic New York, nor do we know how the courts will respond to aggressive Republican-drawn maps in Ohio and North Carolina. But in terms of predicting the actual results in 2022, other factors matter much more than any slight change in lean. For one thing, most of the seats that have gone from leaning-Republican to leaning-Democratic are already held by Democrats, so they don’t present pickup opportunities. By contrast, nearly all of the newly-Republican-leaning seats are also currently held by Democrats, and so represent enhanced opportunities for Republicans. Then there’s the fact that Biden ran significantly ahead of the congressional Democratic Party in 2020. Benchmarking redistricting’s impact to the presidential race, then, is effectively padding the Democrats’ apparent position. Finally, and most importantly, the dominating factor for the midterms is almost certainly going to be the president’s approval rating, which is currently well under water.

But what the results do suggest is that gerrymandering might not be the democracy-killer that some have made it out to be. An egregious gerrymander aimed at maximizing partisan advantage will leave little room for further map “improvements.” As natural thermostatic movement away from an incumbent party erodes the edges of that apparently entrenched majority, that party may be faced with the choice of reducing the scale of its majority to shore up what remains, or facing the possibility of a larger-scale defeat. That doesn’t mean gerrymandering should be permitted—there’s no good reason at all to let partisan politicians draw their own districts—but it does suggest that there are real practical limits to how much a majority party can do to prevent themselves from electoral accountability.

Or is there? While the map looks likely to be slightly more favorable to Democrats than the 2010 map that it will replace, it’s significantly more favorable to incumbents:

The far more dramatic effect of 2022 redistricting: a rise in the number of hyper-partisan seats at the expense of competitive ones. So far in completed states, the number of single-digit Biden and Trump seats has declined from 62 to 46 (a 26 percent drop). That means a House even less responsive to shifts in public opinion, with more ideological "cul-de-sac" districts where candidates' only electoral incentive is to play to a primary base.

I think there’s a good argument to be made that this, rather than partisan lean, is the true democracy-killing aspect of gerrymandering. Yes, in a given state, a Republican or Democratic majority can draw maps that tilt representation away from a “fair” partisan split—though what constitutes “fair” may also be debated. (There are Republicans in Manhattan, for example, but there’s no possible district you could draw where they would be a majority.) But there are diminishing returns to such a strategy. By contrast, it’s much more straightforward to minimize political risk to representatives from both parties—especially if the parties collude, as they are generally happy to do. Moreover, the process is self-reinforcing. As fewer and fewer districts are genuinely competitive, the parties become less and less responsive to anyone but the base voters who determine primary results—and this either causes less-partisan voters to drop out of the political process, or to choose sides perforce.

Most proposals for banning gerrymandering implicitly suggest that a “fair” map is what’s most important—something that most-closely reflects the partisan composition of the state in question. But there’s an inherent tension between that goal and the goal of a “responsive” map that maximizes the number of districts that are genuinely competitive. For the purposes of democratic accountability, I’m inclined to think that it would be preferable for a map to be tilted a couple of points toward either party if that made it possible to make many more districts competitive, and therefore made it more likely that the majority would shift back and forth in response to the incumbent party’s performance. The size of a majority is, in the end, less important than its durability.

Unfortunately, drawing maps that maximize accountability is getting harder: in that respect, the gerrymanderers have the wind at their backs. Democrats and Republicans increasingly live lives that are physically segregated from each other. If we live in the same state, we live in different counties. If we live in the same county, we live in different neighborhoods. And in the rare circumstance where we live in the same neighborhood, we still manage for the most part to avoid meeting. In such circumstances, it may seem only natural to draw districts dominated by a single party—that’s the most important interest people have in common, and the point of a single-member district is for that member to represent the district’s interests.

It may seem natural, but it’s not conducive to the accountability that is essential for a functioning democracy.