Why Is This Year Different From All Other Years?

At my Seder, I rejected timeliness. Was that wisdom, or evasion?

Earlier this week, I promised to deliver a Passover-themed post before the end of the holiday. I suspect many of my readers were anticipating something that would point out how the story of the Exodus, or the ritual of the Passover Seder, or this or that passage in the Haggadah, relates to the many ways that freedom is threatened right now. A number of people I had at my Seder expected it as well—indeed, some asked specifically for something related to the hostages who remain in captivity in Gaza.

And I could have done that—easily. I can’t recall a year where it has ever felt like there were so many things to talk about. I could have talked, for example, about how Joseph as grand vizier helped to concentrate economic power in Pharaoh’s hands, and thereby set the stage, when a new Pharaoh arose who had no loyalty to Joseph or his people, to turn on the Israelites and make them into slaves. That has plenty of analogies for our times, starting with Congress’s abject abdication in the face of an unprecedented presidential power grab. Or I could have taken a more Jewish-centered tack on the same story, talking about how some high-profile Jewish support (by no means ever a majority much less unanimous and increasingly being reversed) for this administration’s arrests and attempted expulsions of non-citizens who vocally oppose Israel seems destined to redound to our profound detriment.

I could have talked about the hostages rotting in their pits of darkness. But I could also have talked about how we remove drops of wine from our cups as we recount the ten plagues as a gesture toward the suffering of the Egyptians, or how God rebuked the angels rejoicing at the drowning of the Egyptians in the Red Sea, and asked how we should think about the spirit of vengeance that is so prominent in Israel today. If I really wanted to go there, I could have talked about how Israel’s ministers increasingly use Pharaonic language about thinning a hostile population when they speak about the Palestinians.

And of course I could have talked about America’s new Salvadoran gulag. The list of possible topics is long, long, long. I wonder if that’s why I decided I didn’t want to talk about anything contemporary at all.

For my entire life, people have been tinkering with the Haggadah to speak to current concerns. On the brink of the establishment of the State of Israel, members of the Haganah wrote Haggadot explicitly connecting their efforts to achieve independence with the exodus from Egypt. I remember my father used a Haggadah at his Seders that talked about the Holocaust, and I can remember him adding readings in the 1980s about the plight of Soviet Jewry. Also in the 1980s, I can remember sitting at my mother’s Seder table during the First Intifada debating whether Israel, in its policies toward the Palestinians, was behaving like Pharaoh. (It seems so quaint to think about that now.) I’ve been at plenty of Seders where the hosts put an orange on the Seder plate, a custom originating with Susanna Heschel that is about the inclusion of women, and lesbians specifically, in full Jewish participation. This year we were all supposed to add a lemon, at the behest of the parents of slain Israeli hostage Hersh Goldberg-Polin.

I didn’t want any of it. I don’t know if that’s because I didn’t want to point my finger outward at an oppressor when I could so easily point it inward, or if it was the other way around. Or perhaps I simply felt like people had been doing this for so long, this search for contemporary applications, that those kinds of gestures had been drained of real meaning. It began to feel to me like needing to point to the thing was proof you were not actually face to face with the thing. If you were, you wouldn’t need to point. But is that true generally? Is it even true for me? Or is the opposite true—am I resistant to pointing because I am actively trying not to face the thing?

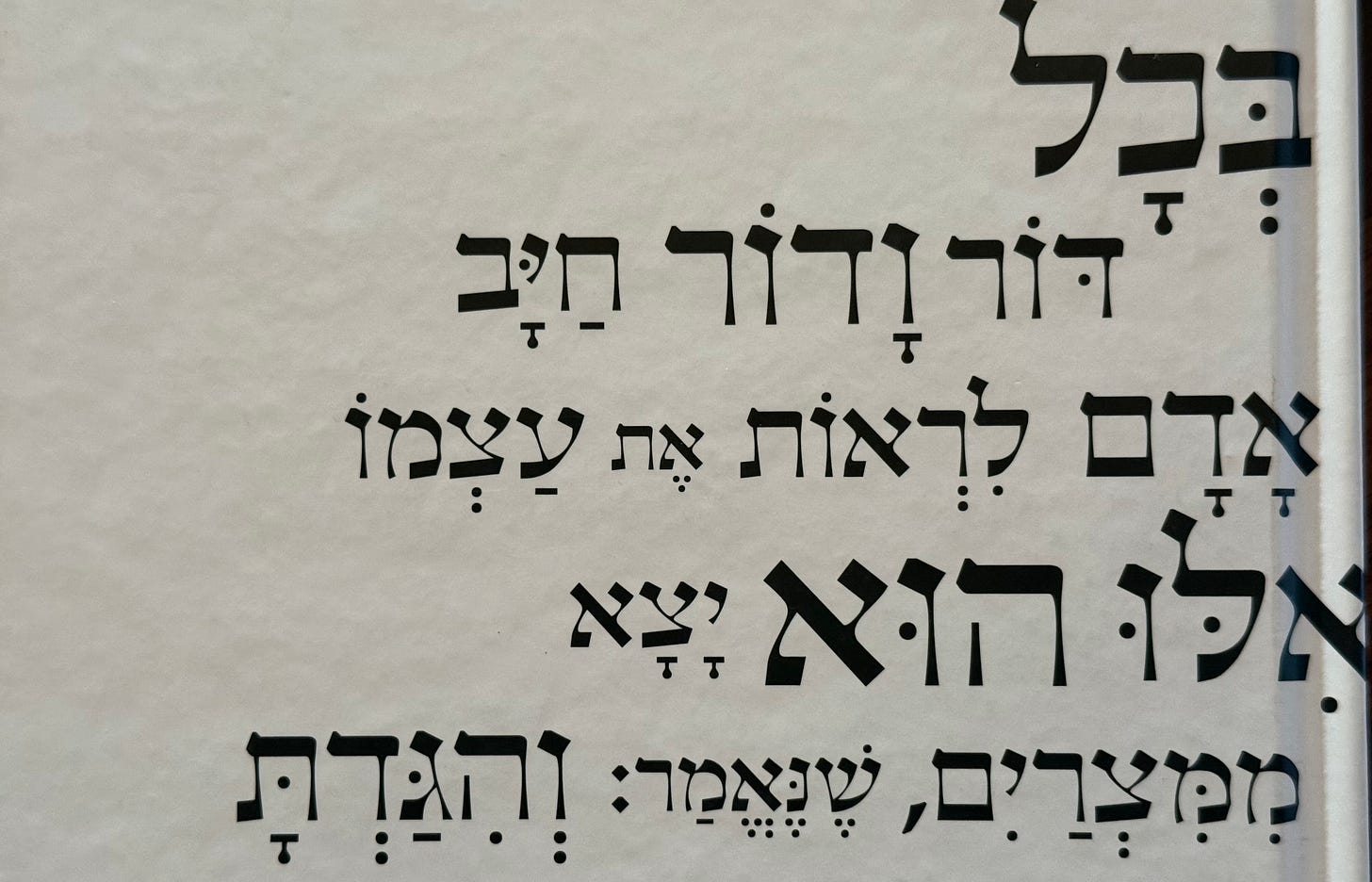

Meanwhile, the one thing I did say at my introduction to the Seder was way out on a limb—and revealingly so, I think. I pointed out that the Seder was celebrated in the most dire circumstances in the past—starting with the original Seders that were observed while Judea was revolting against Roman occupation, and continuing down to Seders observed surreptitiously in the ghettos of Nazi-occupied Europe and even in concentration camps—which is completely true. And then I said that part of the point of celebrating freedom in such circumstances is that the Exodus had effected an existential change: God had liberated us, and after that liberation even if someone enslaved us, we retained the inherent status of free people. I know I believed it when I said it, but I’m not sure where I thought I was getting it from; I certainly didn’t have a proof text to hand. In fact, the text of the Haggadah itself says “this year we are slaves; next year, may we be free people.” That passage was added after the destruction of the Second Temple, the catastrophe that ended Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel, a collective status change that the rabbis most certainly recognized. Why didn’t I remember it less than half an hour before I would be singing it?

There’s another passage in the Haggadah that I’ve been fond of highlighting for decades. It comes right after the recitation of the ten plagues, and right before dayeinu, the famous song of thanks for all the wonders that God performed for His people, and recounts a debate between various rabbis in which they multiply the number of plagues, and therefore the magnitude of the miracle. The first one says that while there were ten plagues in Egypt, the drowning of the Egyptian army in the Red Sea constituted fifty plagues, because of the plagues in Egypt the Bible says “this is the finger of God,” while at the Red Sea it refers to God’s hand. If the finger caused ten plagues, then the hand must cause fifty. (This is how we know God is not a Simpsons character: because Simpsons characters have only four fingers on their hands.) Then a second uses a proof-text to demonstrate that each plague is actually four plagues rolled into one, such that there were actually forty plagues in Egypt and two hundred at the Red Sea, and then a third parses the same proof-text slightly differently to demonstrate that each plague is actually five plagues rolled into one, such that there were actually fifty plagues in Egypt and two hundred and fifty at the Red Sea.

Maybe it’s just because I used to work in financial derivatives, but every year I find the whole section incredibly funny. But I also delight in pointing out that earlier in the Haggadah, we heard of these same rabbis staying up all night to discuss the Exodus until their students came to tell them it was time for morning prayers. Why didn’t they know it was morning already? Because they were conducting their Seder in secret, in a cave, out of sight of their Roman persecutors—but also far from the sunlight. So in the most dire circumstances, they were determined to have a Seder, and this is what they spent the Seder debating about.

Each year I make a joke about this—but also I know that there’s a poignancy to these men, on the run from the authorities, imagining God smiting their pursuers with two hundred and fifty plagues with a single blow from the divine hand. It feels to me like an expression of despair as much as it is of hope. When you’re counting on God sending two hundred and fifty plagues to save you, you’ve pretty much run out of options.

Yet one thing that is true about the Haggadah is that it is emphatic about liberation being in God’s hands. That’s why the text very nearly erases Moses from the story. Over and over, the text says, liberation from Egypt was something God did for me, not something I won or that was handed to me by some lesser mortal savior. In this populist era, where both Trump and Netanyahu style themselves kings and messiahs, that’s one reason I can still put forward confidently for clinging to the traditional text, even at the risk of being irrelevant.

This is a wonderful reflection for me, a practicing Christian, to reflect on today. Many thanks, and a blessed Passover to you and all your loved ones!