What Makes a Redistricting Fair?

Partisan gerrymandering is bad--but there are still tradeoffs

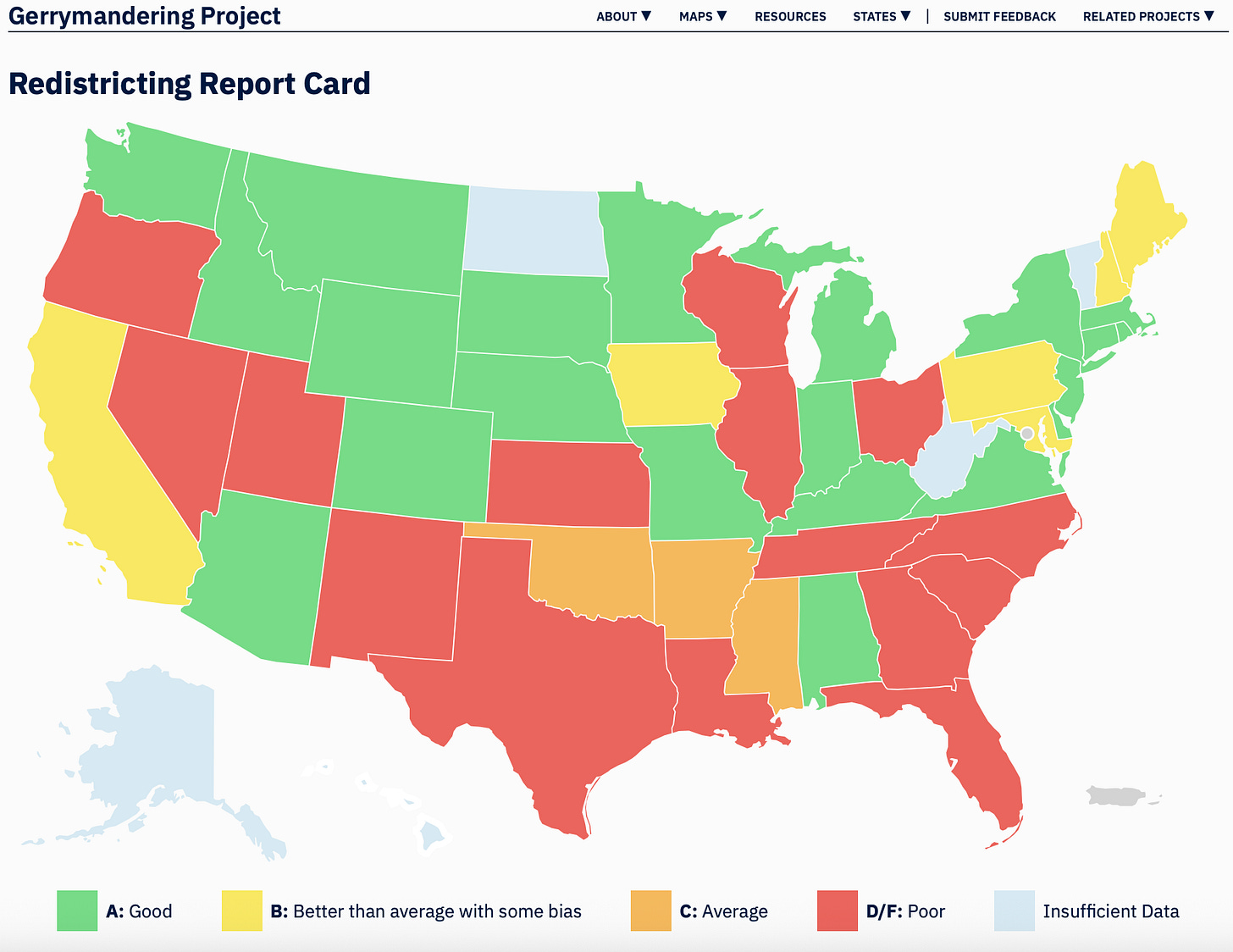

Redistricting Report Card from The Gerrymandering Project

What makes a redistricting map fair? Is it the process or the product—and in either case, what process and what product?

I’m prompted to ask this question, of course, by the proposed Texas gerrymander, aimed at increasing the Republican congressional delegation by five seats. From a process perspective, the objections are obvious. Redistricting only has to happen after a new census, so a redistricting at any other time is presumptively illegitimate. And for any purely partisan redistricting the negative presumption is even greater. There’s something obviously undemocratic about allowing incumbents to set the boundaries of their own districts to keep themselves in office, and to allow incumbent majorities to improve their political position by similar means. One of the teams playing the game shouldn’t be allowed unilaterally to change the rules.

Beyond preventing obvious self-dealing in the process, though, are there any other principles in play? Since the Civil Rights era, courts have thrown out redistricting plans that have aimed to minimize Black and other racial minority representation; racial gerrymanders designed to increase racial minority representation, by contrast, have generally been approved, though it looks likely that the Supreme Court is going to start applying strict scrutiny to these cases as well very soon. The Supreme Court has consistently refused in recent years to touch political gerrymanders, but just because the Supreme Court allows something doesn’t mean it’s fair. Hence the question: how can we tell if a redistricting is fair?

The Redistricting Reform Act of 2024 attempts to answer that question by laying out a framework that states would be required to follow in their redistricting efforts. The framework, in a nutshell, is as follows:

Mid-decade redistricting would be banned.

Any redistricting would be required to comply with the Constitution’s requirements for equal population and the Voting Rights Act’s requirements prohibiting invidious racial gerrymanders, as well as existing case law promoting the creation of “safe” minority districts.

After those, requirements are met, the next priority for redistricting would be for districts to “represent communities of interest and neighborhoods.”

However, even if a plan complies with all of the above requirements, it will be prohibited if it materially advantages one party over the other in terms of their likely representation.

That all sounds reasonable, doesn’t it? But there are profound tradeoffs built in to that very fair-sounding scheme.

Most obviously, drawing districts to produce the most proportional partisan outcome based on prior elections is unlikely to result in districts that best “represent communities of interest and neighborhoods.” In effect, the law requires gerrymandering to achieve a partisan outcome, it just requires that gerrymandering to be balanced between the parties rather than one-sided, and achieving that balance could require some tortured line-drawing at least for some districts.

Then there’s the question of competitiveness, which doesn’t figure into the criteria at all. Suppose a fairly large state—like Illinois or North Carolina—is split 53%-47%. If, as in many states, those votes are distributed such that the rural areas are overwhelmingly Republican and the urban areas are overwhelmingly Democratic while the suburbs are somewhat split, the opportunities to do a partisan gerrymander would be substantial. (Both of those states have availed themselves of that opportunity.) But you could also probably draw multiple maps that would be fair in terms of partisan split but that would vary widely in their competitiveness. You could, for example, create a handful of overwhelmingly Republican rural districts, or a handful of overwhelmingly Democratic urban districts, but divide most of the state’s population in a way that combined urban, rural and suburban votes such that most of the districts were highly competitive. That would mean that in a wave election, the partisan balance in the delegation would swing substantially from one party to the other—but at the end of either swing, representation would be wildly divergent from the underlying partisan balance in the state. Alternatively, you could maximize the number of safe seats (quite possibly also making them more compact and representative of distinct geographies), locking in something close to the “proper” partisan balance at the price of making the electoral system basically non-responsive to voter discontent.

This tradeoff affects partisan gerrymanders as well as fair maps, because the gerrymandering party can’t simultaneously maximize the chances of potential partisan gains and minimize potential partisan losses. The last Texas redistricting, for example, was as partisan as the new proposal, but emphasized minimizing losses rather than maximizing gains. So should a non-partisan process be blind to the question of competitiveness, and just focus on balance? Or should it aim to maximize competitiveness consistent with not biasing the likely outcome? Consider, in this regard, that turnout varies considerably based on how competitive an election is. We don’t really know the precise partisan breakdown of any given state; we just know the partisan breakdown of those eligible voters who voted. That breakdown could change dramatically if voting more obviously mattered—which is more a function of the competitiveness of the map than of its fairness.

For this reason among others, the more competitive the map, the more likely that it looks biased after the fact, since even a redistricting aiming to be politically-balanced may produce a lopsided partisan outcome as voting patterns shift. Consider, in that regard, this analysis by the Center for Politics of how the proposed Texas redistricting would look based on the 2018 Senate vote as opposed to the 2024 Presidential vote. The former looks a lot dicier for Republicans—not just because 2018 was a much better year for Democrats in Texas than 2024, but because of the changing political geography of the state, specifically the migration of Hispanic voters in the Rio Grande valley toward the Republicans. Does that mean the new map is fairer than its critics have claimed? No, it doesn’t—but it does mean that Republicans aren’t talking nonsense when they say that the redistricting gives them more risk of losing seats as well as more chance for gaining seats, and that the way in which it biases the map in their favor is a reflection of very recent shifts in voter behavior that may or may not be reflective of future behavior by those same voters. I’d make the same bet they are—but it’s still a bet.

Then there’s the question of whether non-biased state maps could, collectively, lead to a biased national map. The smaller the state, or the more uniform its partisan lean, the harder it is to provide representation to its political minority. Indiana and Connecticut get sterling marks for having fair maps. But there are only two Democratic districts in Indiana out of nine despite over 38% of the congressional vote going to Democrats in 2024, and there are zero Republicans in the Connecticut delegation despite over 40% of the congressional vote going to Republicans. The only practical way to provide representation to the minority party in either state is with multi-member districts. In the absence of that, you could have fair state maps that nonetheless generate very one-sided results in partisan terms—and there’s no guarantee that these would offset one another perfectly on a national level.

All of which is to say: what the country needs, for small-d democratic credibility, is a fair process rather than a perfectly balanced outcome. If you want election results to most-accurately reflect the partisan breakdown of the electorate, you need to elect your legislature based on proportional representation, not on a first-past-the-post basis in individual districts. Proportional representation has its own problems of democratic accountability (you vote for a party, but then the party has to form coalitions that might well betray its voters), but if what you care about most is a correspondence between vote totals and seats, that’s the best game in town. But it’s not the American game, and isn’t likely to be.

If I ran the zoo, I’d have the districts of every state drawn by a non-partisan commission, but their mandate would be somewhat different from the proposed Redistricting Reform Act of 2024 in that I would make competitiveness a formal criterion ranked above achieving compactness or representing “communities of interest or neighborhoods.” Frankly, I’d even trade substantially greater competitiveness for a modest amount of bias. Anything that reduces the sclerosis of the system, and makes our representatives more worried about losing their seats to the opposition party than to a primary opponent, sounds good to me. Larger but more fragile and fleeting legislative majorities with a wider range of political views represented in each party strike me both as more likely to be productive and more likely to allow for dissent, both of which would help push against the overwhelmingly partisan tenor of our times.

But I could be wrong. It’s possible that if our legislators couldn’t use redistricting to guarantee themselves permanent jobs, they’d be even less likely to take any risks, and would be even happier to hand over all their power to the executive. In the end, technocratic tinkering with the system can only do so much. There’s no way to engineer an electoral system to produce political courage.