What If We Held a Constitutional Crisis and Nobody Came?

From Tik Tok to tariffs, NVIDIA to immigration, the Constitution is changing--but there's no crisis

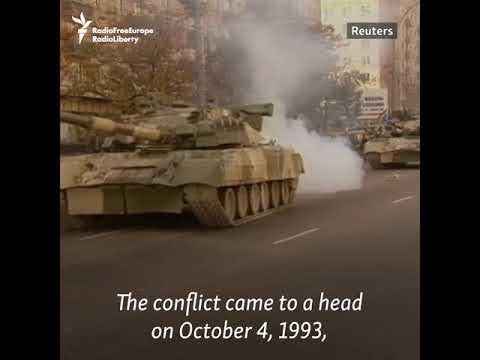

Russia’s constitutional crisis in 1993 was “resolved” when President Boris Yeltsin sent tanks to attack the parliament that had impeached him

The Trump administration has done a lot of things that many people find alarming, from shipping non-citizens to a Salvadoran prison to hiking tariffs to bombing Iran’s nuclear sites to killing funding for vaccine research to deploying the military in American cities to . . . well, it’s a long list, and I don’t need to rehash it. Some of these things are fairly traditional Republican priorities—some are even bipartisan priorities—while others are distinctively Trumpian. Some have quite a lot of popular support, if not necessarily a majority, while others are extremely unpopular. But a commonality of some of them—and extending to some actions that haven’t caused much widespread alarm at all—is the way in which they push or even flagrantly cross the boundaries of presidential power as it has been historically circumscribed.

This is sometimes described as a “constitutional crisis,” but I think that’s a misnomer. A constitutional crisis is when different bodies within a constitutional structure claim supremacy over one another, and refuse to back down in a conflict. For example, if the Supreme Court struck down an executive order, and the administration reiterated the order and said it must still be enforced despite the court’s ruling, that would be a constitutional crisis. Similarly if, say, a governor mobilized the state’s National Guard to prevent ICE agents from entering their jurisdiction to conduct raids, or if Congress reclaimed its authority over tariffs and the administration ordered customs officials to ignore Congress and collect based on the rates the administration had set, those would be constitutional crises. If neither side backed down, then individual citizens—including people directly involved in the conflict, some of them charged with enforcing the law—could not know who was legitimately in authority or what the law might be. In the worst case scenario, the answer would be determined by an outright show of force, which could either succeed (as in Russia in 1993) or fail (as in South Korea in 2024).

That is precisely what is not happening today. On the contrary, what we’ve generally seen is widespread acquiescence in profound constitutional changes, and thereby the avoidance of crisis. Congress has been almost completely inert, even when, as with the Tik Tok ban, the administration has blatantly disregarded a law passed by a substantial majority of Republicans. With regard to tariffs, Congress has handed over to the administration a power explicitly reserved to the Legislative Branch by the Constitution, and seen it become a major source of revenue (eroding Congress’s most central power) as well as a tool for both coercive diplomacy and domestic economic regulation. Blue state governors have been extremely vocal in their criticism, and have sued the administration in some cases (like California’s suit over the deployment of troops to Los Angeles), but they have not asserted their sovereignty in more dramatic and confrontational ways that could precipitate a crisis. And the organs of civil society, from large corporations to law firms and universities, have largely sought to strike deals with the administration, even at the price of agreeing to unprecedented types of presidential interference in their affairs.

That leaves the courts, which could yet check the administration in fundamental ways. But I’m increasingly skeptical that this will happen. Federal courts were quite active from the get-go in rebuking the administration, but the Supreme Court—understandably concerned about preserving their viability and authority within the constitutional structure—has been far more circumspect, reprimanding lower courts for being overly aggressive, moving at its typical deliberate pace to make rulings of its own, and, when they have responded swiftly (as in the Abrego Garcia case), seeking to guide the administration away from a conflict rather than demanding that the administration simply back down. The Supreme Court has also generally blessed the administration’s efforts to seize unified political control of Executive Branch agencies, effectively endorsing a consequential constitutional shift. This could be consistent, of course, with an equally vigorous effort to check the administration when it usurps the Legislative Branch’s prerogatives, but in the three highest-profile examples—the administration’s refusal to enforce the Tik Tok ban, imposition of tariffs, and negotiation of a profit-sharing agreement with NVIDIA—they may well be reluctant to impose that check.

Why? Let’s take them each in turn. In the case of the Tik Tok ban, the case may simply be moot by the time the Supreme Court acts (if Tik Tok is sold or banned), or, if not, the Supreme Court may be reluctant to intrude into an ongoing negotiation, particularly if Congress is not demanding they do so. It seems quite likely to me that either there will be no ruling at all or, if there is one, that it will at least partly affirm the precedent that the Executive can set aside a duly-passed law in order to negotiate a “deal” that it claims is more favorable to the national interest. Something similar may obtain with respect to tariffs, where Congress has to an extent affirmatively surrendered its constitutional authority, and where, by the time the Supreme Court rules on the question (if it ever does) the administration will likely have negotiated a host of trade deals with our trading partners which the court will be reluctant to void. While Congress has to sign treaties for them to have the force of law, negotiating them is an Executive responsibility, and there's ample precedent for such agreements coming into force even before they are signed (leaving them vulnerable to being set aside with a change in administration, but that’s another story). Finally, with respect to the NVIDIA and AMD deals, it’s not clear that anyone with standing to sue has any incentive to do so, since the only obvious parties with standing—the companies themselves—are willing and eager parties to the agreement. If that’s the case, then the administration may again have set a precedent that contravenes the black letter text of the constitution (which prohibits taxes on exports) without generating any pushback.

The pattern of acquiescence and accommodation is broad enough that I really do think it’s wrong to talk about a constitutional crisis, and more appropriate to speak of a constitutional transformation. We increasingly live under a system with Caesarist characteristics, in which the Executive Branch is expected to be directly responsive to the elected president; in which it can be extremely proactive in inserting itself into any given situation, foreign or domestic; and in which, when it does insert itself, it is granted a high degree of deference by the other actors in the system. What’s harder to know is how enduring this transformation will be—whether, in fact, all we’ve done is defer a constitutional crisis until such time as there is a change in the party controlling the government.

It’s conceivable that, if the Democrats recapture both the House and Senate, that they will vigorously reassert Congress’s powers under the Constitution and that, in those circumstances, the Supreme Court would back them up. If the administration backed down in response, that would reveal that the old Constitution still had life in it, and if it didn’t then we’d have a proper constitutional crisis on our hands. But it’s also possible that the Democrats wouldn’t seek to challenge the ways in which President Trump has expanded Executive Branch authority, because they hope to use those powers themselves. Then, were they to win the presidency, they might well find themselves checked by a suddenly more-vigorous Supreme Court and/or a Republican Congress, reclaiming previously dormant powers or drawing new distinctions between what the Democrats might be doing and what Trump did. The same organs that allowed Trump to set extraordinary new precedents, in other words, could precipitate a constitutional crisis by refusing to allow a Democratic president to follow suit. The Democrats could also precipitate a crisis themselves by trying to effect a transformation of their own, whether by expanding the Supreme Court or creating new states on a partisan basis or what have you. Worst of all but entirely plausible would be a situation where the electoral system itself lost credibility because one or the other party refused to accept that their opponents had won, a repeat of January 6th, 2021 but with much higher stakes and a more catastrophic outcome. All of these possibilities loom in the future, regardless of whether the Trump administration is able to achieve their own goals of constitutional transformation without precipitating a crisis.

I understand the motive for acquiescence—indeed, I’m not sure there’s a broadly better strategy available than fighting winnable fights and dodging unwinnable ones. Fear of a crisis, added to the fear of personal violence being directed their way if they stand up, is undoubtedly a major motivator for the widespread accommodation that we are observing right now. But if the goal is just to ride out this unusual moment and return to normal politics in a few years, I think the landscape is being misread. We’re already over the falls. Even if we survive the rocks below, I see nothing but rapids for miles and miles beyond, which we will have to navigate one way or another.

Four months ago, the crisis question was always "When will the administration go far enough that it's a crisis?"

I think this captures well the shift in expectation. "When will someone go far enough in stopping the administration that it's a crisis?" It's nearly the same question but the default has shifted: of course the administration is going and will go explicitly farther than the Constitution allows, but rather than ask if it's a crisis reach, we know that the more unusual thing would be a crisis response. Ambition can't check ambition when incentives are aligned.

That was depressing. It seems to me patently obvious that Trump is trying extinguish democracy and establish authoritarianism. Calling what these fascists are doing "constitutional transformation" seems to be underselling the threat to our mode of government and our society.