What Happens When There's No Job To Learn On?

My current A.I. worry

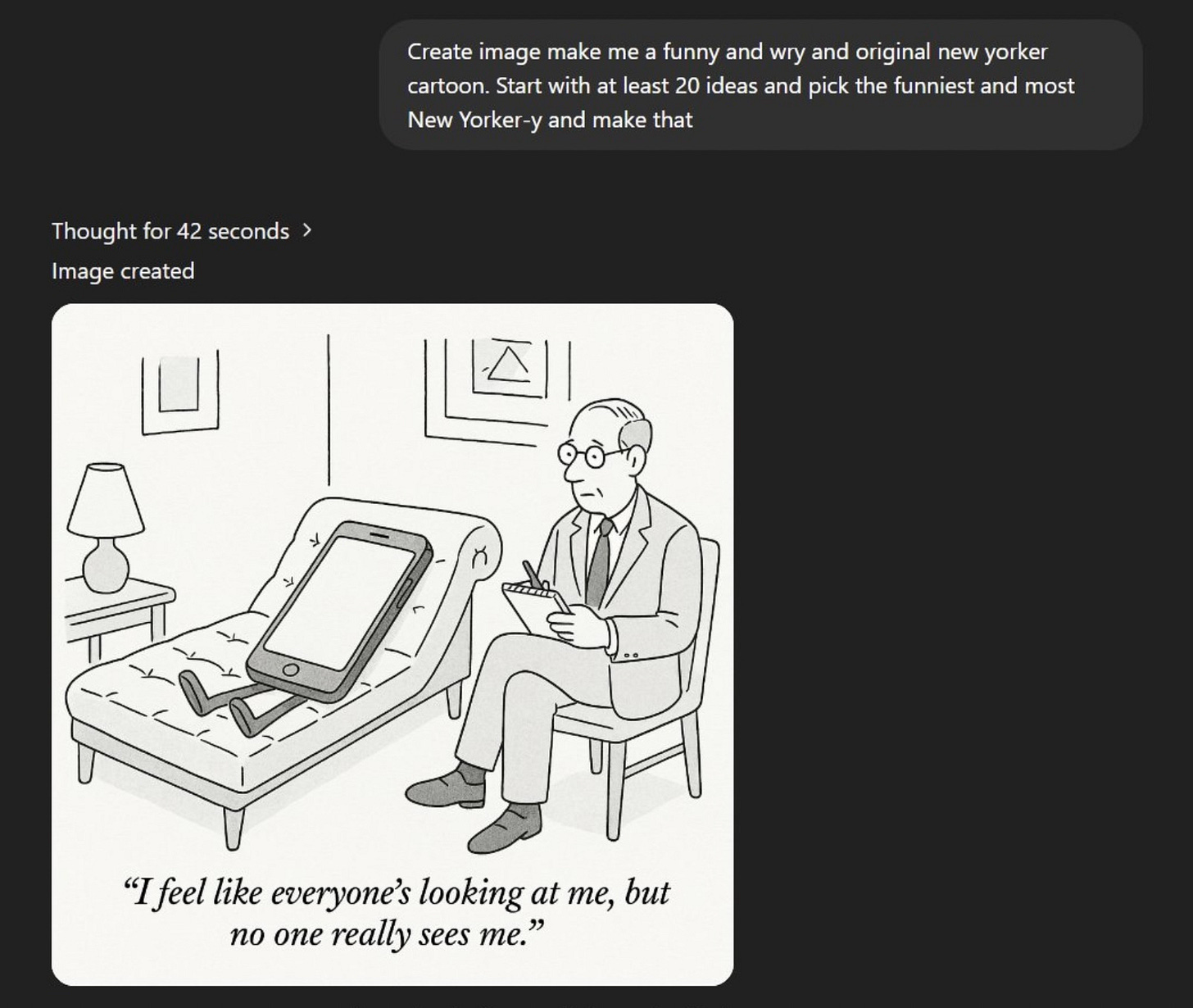

Have you all seen this thread about how quickly o3 can produce quite plausible and clever New Yorker-style cartoons? Here are my two favorites:

Not bad, right? I think intelligent follow-up prompts could improve both cartoons, and you’d need more sophisticated prompting to keep things going for years, but I’m nonetheless impressed that o3 is capable of mimicking a particular style of humor sufficiently well that the results are, if not laugh-out-loud funny, nonetheless coherently amusing. And New Yorker cartoons aren’t generally laugh-out-loud funny; much of the time, they aren’t even coherently amusing. If I were a cartoonist, I’d be worried about my job security.

It’s not too surprising that New Yorker cartoonists would appear ripe for replacement by A.I., if only because the magazine has such a distinctive and eminently-imitable style. Part of that style, though, is precisely the inscrutability I was talking about in the previous paragraph. I do wonder how long it will take A.I. to achieve that, if it ever will. But I wonder more whether human beings will be able to achieve the state of utter bafflement that attends the best New Yorker cartoons once we’re living in an A.I.-dominated world.

This is not what most people worry about when it comes to A.I. The more familiar worries include: Maybe A.I. will attain super-intelligence, will be misaligned, and will destroy humanity (the Skynet scenario). Maybe it will attain super-intelligence, will be properly aligned, and cause humanity to atrophy and ultimately die off from a sense of purposelessness (the Wall-E scenario). Maybe it will never achieve super-intelligence, but will still wreak havoc by being wildly misaligned (the paperclip-maximizer scenario), or will be used by malign actors to ruin life for everybody (the Nigerian super-scammer or basement-dwelling bioterrorism scenarios). If none of these downside scenarios happen, though, then A.I. promises to be a huge boon to humanity, relieving us of an enormous amount of drudge work and thereby making us all wealthier and freer. The transition may be painful, as other technological transitions have been, and profound political changes may be necessary to tame the new technology to appropriately social ends. But we should still be profoundly grateful for what will ultimately be a new and powerful tool to promote human flourishing.

But will humans continue to flourish? Let’s take the cartoonist example above. Assuming A.I. permanently remains a tool, you’d still need human beings to prompt the A.I. to produce cartoons. If the A.I. never got much better than it already is, then human beings would have a significant role to play in refining and enhancing the A.I.’s output. And, as noted, the A.I. might never get good at being idiosyncratic and weird in a distinctly human way; it may be able to be funny, but in a blandly predictable way.

So we can imagine a future where The New Yorker continues to hire cartoonists, and they continue to “draw” cartoons, but now with A.I. as an assistant. Instead of working all day on an idea, they’d prompt an A.I. to produce 100 ideas, and then work with the A.I. on refining the best one. Maybe they’d even do some drawing to give the A.I. more clarity on where to take an idea, or to put the “human touch” on a design. Working with A.I. would be like supervising an incredibly accomplished junior cartoonist. Maybe The New Yorker wouldn’t need to employ so many cartoonists (they certainly wouldn’t employ many of the staff who still produce the magazine), or maybe they’d publish far more cartoons than they used to. Maybe New Yorker cartoons would come to be highly customized to individual readers, and the human cartoonist wouldn’t actually draw any cartoons but rather adjust the parameters of the A.I. to assure that these customized cartoons still had the proper human feel. Regardless, there would still be human beings involved, and they’d be making more and better art than they ever did with their A.I. assistants.

But what happens when those cartoonists retire? Well, they’d be replaced by the next generation of cartoonists, right? Except . . . where did that next generation of cartoonists come from? The next generation would have grown up with A.I. all around them, and would have always used it to produce new work. Would they ever have learned to draw? Would they ever have learned how to construct a joke? Perhaps they would—but it’s not clear that they would need to, so you’d expect that fewer people would do so, and that many of those who did would not advance as far or get as much practice. As a result, they wouldn’t have the same insights that older cartoonists had about the possibilities of the medium. They wouldn’t have the experience of being a cartoonist under their fingernails. I have to suspect that, as a result, they’d have a harder time providing that human touch, or adding value to the A.I. in any way.

Maybe cartoonists aren’t the best example. So let’s think about engineering. A.I. is already able to do a great deal of basic coding. I have no doubt it will be able to perform similarly in other engineering-related fields. It’s not hard to imagine, without positing dramatically greater advances in LLM capabilities, a future in which much of the process of building or making anything is outsourced to an A.I. The next generation of engineers will grow up using A.I. to solve basic problems all the time—they’ll never have to solve those problems without its help. As a result, though, they’ll never really have their hands in the guts of what they are making, and they won’t really understand, at a tactile level, how those guts work.

But innovation often comes precisely from getting your hands dirty. That’s one of the key reasons to worry about the fact that America has outsourced so much of its manufacturing to China (and other countries)—the people who are actually doing the manufacturing are in the best position to see ways both to improve any given process and to use it for new ends. When you outsource the doing, you also outsource the learning.

Of course, you can create artificial environments in which you have no choice but to work on your own, and thereby force people to get the kind of experience they need to learn. Schools are trying to figure out how to do that now, faced with an epidemic of students using A.I. as a crutch both to read and to write. But that’s a stopgap measure, because if people are going to use A.I. to do all their reading and writing in the workforce, then for employers the value of reading and writing will drop. The same goes for anything else A.I. does well, including writing code and other engineering work. You can create these artificial environments, but how many people will put in the time to master them?

Now, I’m positing that we still need people to oversee the A.I., because it hasn’t achieved super-intelligence or anything like true agency. So we still need highly capable people who can make sure the A.I. has executed its task properly and also to nudge it with further prompts to do something more creative or insightful. But where will these people come from? The apprentice jobs, which often consist mostly of drudge work, will have been eliminated. That means most people won’t need to acquire these kinds of skills—or if they do acquire these kinds of skills, they won’t be employable. Will we be able to identify talented and hard-working individuals well enough, and force them to acquire experience that gets their hands dirty enough, that they’ll be able to oversee the A.I. at the high level desired?

Right now, we’re still in the steep part of the sigmoid function of LLM development. None of us really know how close we are to the second inflection point, or what kind of physical constraints will cause that inflection, and therefore what LLMs and their relatives will ultimately be able to do. Even if they don’t advance that much further than they already have, however, they’re already in a position to make huge swathes of the workforce obsolete. That’s usually described as a transition problem—buggy whip makers going out of business because of the arrival of the automobile, but being too old to be retrained as auto mechanics. But what if that’s not the right analogy. What if it’s more like replacing yeoman farmers with plantations run by slaves? Leave aside questions of distribution; how much do the people who run the plantations wind up knowing about farming?

In most fields, talent rises through the ranks. What happens when there are no more ranks to rise through, because A.I. has replaced all the lower and even middle levels? Might we wind up with a situation where, instead of delivering miracle after miracle, A.I. delivers a future of highly competent mediocrity, not because it couldn’t be used to more sublime ends, but because we won’t remember how to achieve such things?

I think you see what you're talking about in movies, specifically in musicals. When the genre - and the studio system that made it viable - died (Killed off by Hello Dolly and the like) no more people came up through the system learning how to do those kinds of movies. No more Alan Freeds, no more Busby Berkleys, no more Stanley Donens or Vincente Minellis, no more Fred Astaires or Cyd Charisses or Gene Kellys. So now, when a musical is occasionally made, (La La Land), something is missing. It's thin somehow, lacking all that "thick" experience that was built up over decades. And it can't be recovered or learned on the fly - there's no longer anyone alive qualified to teach it.

And don't even get me going about what CGI has done to stunt driving!

I teach machine learning so I'm acutely aware of the skills gap you point to here. Yet I tend to think of it as a *revealed* skills gap rather than a *developing* skills gap.

Before G.AI, creative writing and visual art were go-to examples of something robots didn't have the proper souls to excel at. Before symbolic AI, chess and mathematics understood as uniquely dependent on human insight. In both cases, this turned out to be wildly inaccurate.

To me, this seems like pretty strong evidence that we have remarkably poor insight into what our "uniquely human" capabilities actually are. Thus, we should be considerably more cautious with AI prognostications. It might even be wise to bet *against* any scenario someone can describe, since the reality has consistently violated our stereotypes.

There are might be some narrow insights available about AI's trajectory (e.g., I suspect sophisticated, flexible motor movements are going to be tricky because there's no analogue to smart phones for collecting large samples of mechanosensory data). But hey, you should probably bet against me! The larger socioeconomic impacts are so intrinsically unpredictable it's best to treat any forecast as mostly bull.