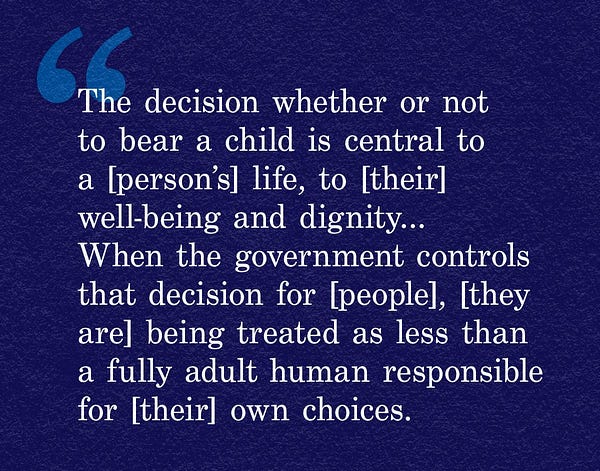

We Hold These Truths To Be Subject To Revision

As they always are. Texts, however, should be left as they are.

Jefferson’s redacted bible; Photo: Hugh Talman, Courtesy of the Smithsonian Museum

I remember vividly the time I sat down to try to read my son The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. I don’t recall what prompted me to do so. I don’t believe I had read it myself as a kid, and I must have known that Twain would be a challenge on multiple levels. I guess I felt like we’d been shortchanging Americana that month; I don’t know.

What I do know is: it was not a success. I first faced the Hobson’s choice to either read in dialect (which was likely to be both confusing and humorous in the wrong way, while also teaching him to do something now frowned upon in polite society) or not (which was certain to be confusing, and would neuter the prose of much of its interest). On page one I had to explain that corporal punishment is normal in this world, and on page three that boys in this world like fighting for no reason. I dreaded the first moment that Twain referred to a Black person, knowing not only what word he would use but that no substitute word that I might substitute would in any way dull the implications of the text’s larger characterization. By mutual agreement, we gave up almost immediately.

Which is fine. There were plenty of other books for him to read and for me to read to him—plenty of them books about scamps. We had a grand old time with the Petit Nicolas books, for example. My son didn’t need Mark Twain and Mark Twain doesn’t need my son; they’ll both be just fine without meeting. And if my son choses to read him later in life, he’ll still be there on the shelf—provided we leave him there to be found and read.

All of which is by way of prologue to the tweet that everyone’s been yammering about:

The ACLU has been rightly raked over the coals for this absurd tweet, but not always for the right reasons. There is no violation here of the principle of “free speech,” for example—Ruth Bader Ginsburg is not being silenced by anything but the grave, and her actual words are still readily available to anyone who wants to find them. Nor is the problem that the ACLU is trying to avoid using quotations that contain language that contemporary Americans might reasonably construe as offensive, even if, in their proper context they should not be interpreted as such.

I don’t even think the real problem is that the ACLU has staked out a position on what constitutes offensive language that is wildly out of line with what contemporary Americans actually think (indeed, a position that probably offends more Americans than the language they oppose does). It is wildly out of line, but that, after all, is quite frequently the case with distinct minorities: they can be offended by something that the majority finds innocuous, and when they object the majority is offended at the suggestion that they have to change their language. That doesn’t make the ACLU correct of course—they could simply be wrong on the merits in this particular case. But the kind of thing they are doing isn’t wrong simply because it pisses many people off and looks ridiculous to many others.

No, the problem is that the ACLU bowdlerized a quote to drain it of a good portion of its plain meaning. Ruth Bader Ginsburg wasn’t talking about the rights of “people”—she was talking about the rights of “women.” She was making a claim that those rights are distinctive in ways that men—whom she was largely arguing with—frequently did not appreciate because they had a different relationship to pregnancy. Indeed, she was saying that a lack of recognition of that distinction constituted discrimination, as treating not anyone but a particular class of people as less than fully adult human beings. With their change in wording, the ACLU directly erased that argument, by erasing the existence of that distinct class. They changed the fundamental meaning of her words, as surely as if an anti-abortion group had quoted only the second sentence and replaced the words “less than” with an ellipsis to make the sentence say the opposite of what it originally did.

Why did they do this? It is hard to credit that the reason was that they believed that quoting someone using the word “woman” in this way would be too horribly offensive. Even if they genuinely believe that their preferred language is the more inclusive choice, and that refusing to use it is bigoted, they can’t be unaware that they are, in fact, promoting a change in usage, and that the quote antedates that change. They could easily have quoted Ginsburg accurately, but embedded the quote within a tweet that talked about the rights of abortion in language that they found more inclusive (whatever that language might be). All that would have done was reveal that they were using different language than Ruth Bader Ginsburg herself used, and, might have been seen as implicitly rebuking her. I can’t help but wonder whether that’s ultimately why they didn’t opt to be open in that way: because they aren’t quite ready to tear down a statue that they themselves erected only a few short years ago.

The heart of the matter, though, is that if Ginsburg’s argument is correct, then there needs to be a way, and a word, to describe the class she was concerned to protect from discrimination. If the ACLU knows no such word, they should think hard about what that implies about their ability to defend that class of people’s rights. On the other hand, if they think her argument is incorrect, or merely dated and obsolete, then that in itself is part of the history of feminist jurisprudence that ought to be visible, not obscured.

Since they did neither, that suggests they view the target audience for their tweets as akin to children to whom they are reading a bedtime story, rather than fully adult human beings responsible for their own choices.

This is the perfect response. Leaving all of the inflammatory gender debate aside, we need to be able to name the group we’re talking about in this context.

Women? Biological women? Uterus owners? Women & trans men & non-binary AFAB?

I have opinions. But whatever term we choose, we need to be able to refer to this class. Making our language so incoherent that it can’t do this basic, essential thing is not going to work.