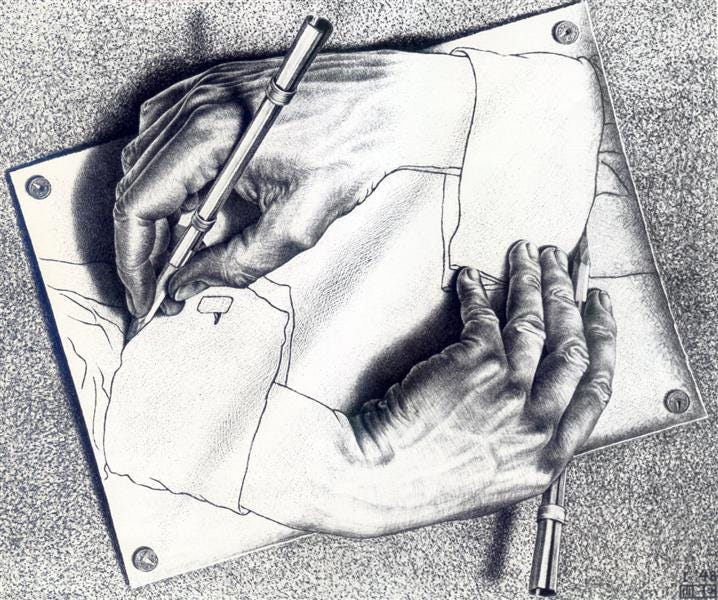

Drawing Hands by M.C. Escher, 1948

Earlier this month, I read for the first time Laurence Sterne’s classic novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, which I enjoyed, but not as much as I expected I would. Now I am reading Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire, about which I feel somewhat similarly: I’m enjoying it, but I’m not falling in love the way I thought I would.

I’m not entirely sure why. I’m tempted to say that they are both books that would have appealed to me more when I was younger, that with age I’ve grown less-enamored of books that, to some extent, take the form of puzzles that must be solved. One of my favorite books in all the world is Ulysses, and I’m genuinely disturbed by the thought that if I encountered it for the first time today I wouldn’t connect with it the way I did in my 20s.

But I’m not sure that’s quite right. First of all, I’m not even sure it’s a proper characterization of those three books. Pale Fire is definitely a kind of puzzle, but Tristram Shandy, while it contains a number of private jokes that went past me (in part because they are mostly in Latin, which I do not know), is not itself a puzzle so much as an experience of a mind in motion. In that it very much resembles Ulysses. Pale Fire is also highly controlled, with the actual author hidden and remote behind his fictional avatars, while Tristram Shandy feels like it really was written the way the fictional autobiographer claims to be working, lacking any organized plan but entered into merely by writing a sentence and letting the next sentence take care of itself. They’re ultimately quite different kinds of books indeed.

The one thing they do have in common, though, is that they are both examples of metafiction, writing that is fundamentally about the fact of being a work of writing. In Tristram Shandy, narrative almost completely collapses from repeated and even nested digression, as if finishing a story were akin to finishing a life, and both reading and writing were delusive ways of staving off the inevitable end. And yet, that effort of staving off may have its own dire consequences, within the book and in life. The entire novel takes the form of an excuse for why the fictional autobiographer never did anything with his life; reading the book, one can’t help wondering whether reading the book is itself a pointless digression from the life one might be living, and yet one winds up hard-pressed to identify what that life might consist of but other digressions. I found that to be a very melancholy feeling, and not a welcome one, particularly as I am prone to feelings of not having adequately lived.

In Pale Fire, meanwhile, the reader and the writer are in a kind of war over the text. The putative author, Charles Kinbote, presents his book as a commentary on the final poem written by a sub-Frostean American poet, John Shade. But in fact the book is a attempted hijacking of that poem by the commentator for Kinbote’s peculiar and paranoid political ends, revolving around a revolution in his home country of Zembla. In actual fact, meanwhile, the contest is not between Kinbote and Shade but between the reader and the actual author, Vladimir Nabokov, to determine the actual relationships between these fictional characters and, therefore, the actual meaning of the combined text in question. I’m finding it amusing, but also kind of depressing if I take it as a metaphor for what we generally do when we wrestle with a text. Am I just engaged in a hijacking when I try to come up with something novel to say about Macbeth, as I hope to do in a forthcoming piece? And are my readers supposed to spend their energy pulling Shakespeare and myself apart? What’s the point of it all if so?

I don’t know. Perhaps my reaction is actually a sign that the books are doing their work all too well.

In any event: I had a socially busy week this week that also featured my finally making progress again on a new screenplay. Whether that endeavor is a digression from what I ought to be doing, or whether this Substack is a digression from that, I leave to the reader to decide. In any event, this will be a briefer-than-usual weekend wrap.

Good Faith Assumption

Earlier this week, the Supreme Court ruled against former President Donald Trump in his suit to prevent White House records related to the January 6th attack on the Capitol from being released to the congressional committee investigating the events of that day. Trump claimed executive privilege, which President Joe Biden had waived, but the Court ruled 8-1 that even if Trump were a sitting president, executive privilege could not be invoked as a shield in these circumstances. All three of Trump’s appointees to the Supreme Court were in the majority.

My column for The Week this week was about important facts like these are for establishing that the Court, even if it is ideologically tilted in a conservative direction, is not simply acting as a partisan body, which in turn is essential since any effort to prevent subversion of a future election by partisan state legislatures or Congress will reply on the Court to be the final arbiter of disputes.

An effective reform of the Electoral Count Act would address this problem [the risk of a genuinely illegitimate election result] head-on. Properly designed, it would remove any lingering responsibility in Congress for resolving disputes about slates of electors, and it would also prevent state legislatures from interfering with the election count or removing election officials without cause. A number of Senate Republicans seem amenable to such reform precisely because they don't want the responsibility for either standing up to Trump or knuckling under if the events of 2020 repeat themselves.

Such a reform, though, would require the courts — federal courts, since reform legislation would nationalize many of these questions — to decide any disputes that might arise. Courts would rule whether a state legislature had improperly removed a county-level elections supervisor, whether ballots were being rejected in an ad hoc manner with partisan intent, or even which slate of electors to accept in the event that we see a repeat of 1876. The legitimacy of a disputed election in the eyes of the public, then, would depend on the legitimacy of the federal courts and, ultimately, the Supreme Court.

And there's the problem. Ever since the 2000 presidential election was only resolved with Bush v. Gore, many Democrats have viewed the Supreme Court through an increasingly partisan and not merely an ideological lens. The see Republican-appointed justices as doing the bidding of their appointer's party rather than merely following an judicial ideology with which Democrats disagree. Now that the court has a 6-3 conservative majority that includes three Trump appointees, the impulse to question the Court's legitimacy has grown far stronger.

I came across an example of that impulse in action the same day my column came out. In an opinion piece in The New York Times about the possibility that Madison Cawthorn might not be eligible to run for Congress because of his alleged role in the January 6th attack, the author—after walking through the legal questions at issue—suggested that if Cawthorn lost in the North Carolina courts, he might find a friendlier hearing at the U.S. Supreme Court because Trump appointed three of the Justices.

I wrote a thread about the this kind of casual assumption of bad faith.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with trying to rein in the courts, either in general or in particular areas. I don’t even think there’s a contradiction between saying that they should be more involved in one area and less involved in another.

But if we casually assume that judges vote in a partisan manner, then the courts’ decisions begin to be seen as illegitimate, and then they can’t perform their function appropriately in areas where we do want them to have a say. That’s going to be a problem if we then decide to rely on the courts to protect the integrity of our elections, as we seem likely to do.

The Art of Losing

My only post on this site this week was about the film, The Lost Daughter, directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal and starring Olivia Coleman. I was less-enamored of the film than most critics have been, but unlike some who have been critical, I think the problem with the film is structural rather than being related to ways in which it departed from the book that is its source material.

The film answers [questions about the main character’s motivation] by means of an extensive series of flashbacks to Leda’s life as a young mother, overworked and lacking in sleep, loving her children and irritated by them, dissatisfied with and ignored by her husband, and desperate for some respite, some opportunity to be herself and use her intellect. This, we’re to believe, is what resonates with her about Nina’s situation, and explains her conduct in the present.

That’s all well and good. The problem is that explanations aren’t what films are about. By spending all this screen time in flashback, and locating so much of the meaning of the present action there, Gyllenhaal drains her present of mystery, even of interest.

I can readily imagine the alternative film, where Leda behaves exactly as she does in this version, but without the explanation of the flashbacks. She’s irritated by the American tourists. She forms a connection with Nina. She saves the daughter. She steals the doll. She flirts with the innkeeper, but doesn’t have a liaison with him. This woman is a mystery. I want to know why she’s doing what she’s doing. Is she Nina’s friend? Is she her enemy? Why is she either? Her behavior is enigmatic, and draws us in. And when she reveals to Nina, late in the movie, that she once abandoned her children, the revelation lands on us as it lands on Nina, snapping into place all that we’ve seen her do.

Particularly if you’ve seen the movie (and especially if you’ve read the book), do read the whole thing. I hope to write more film-related stuff later this week and more generally, so I’m frankly looking for encouragement to do so.