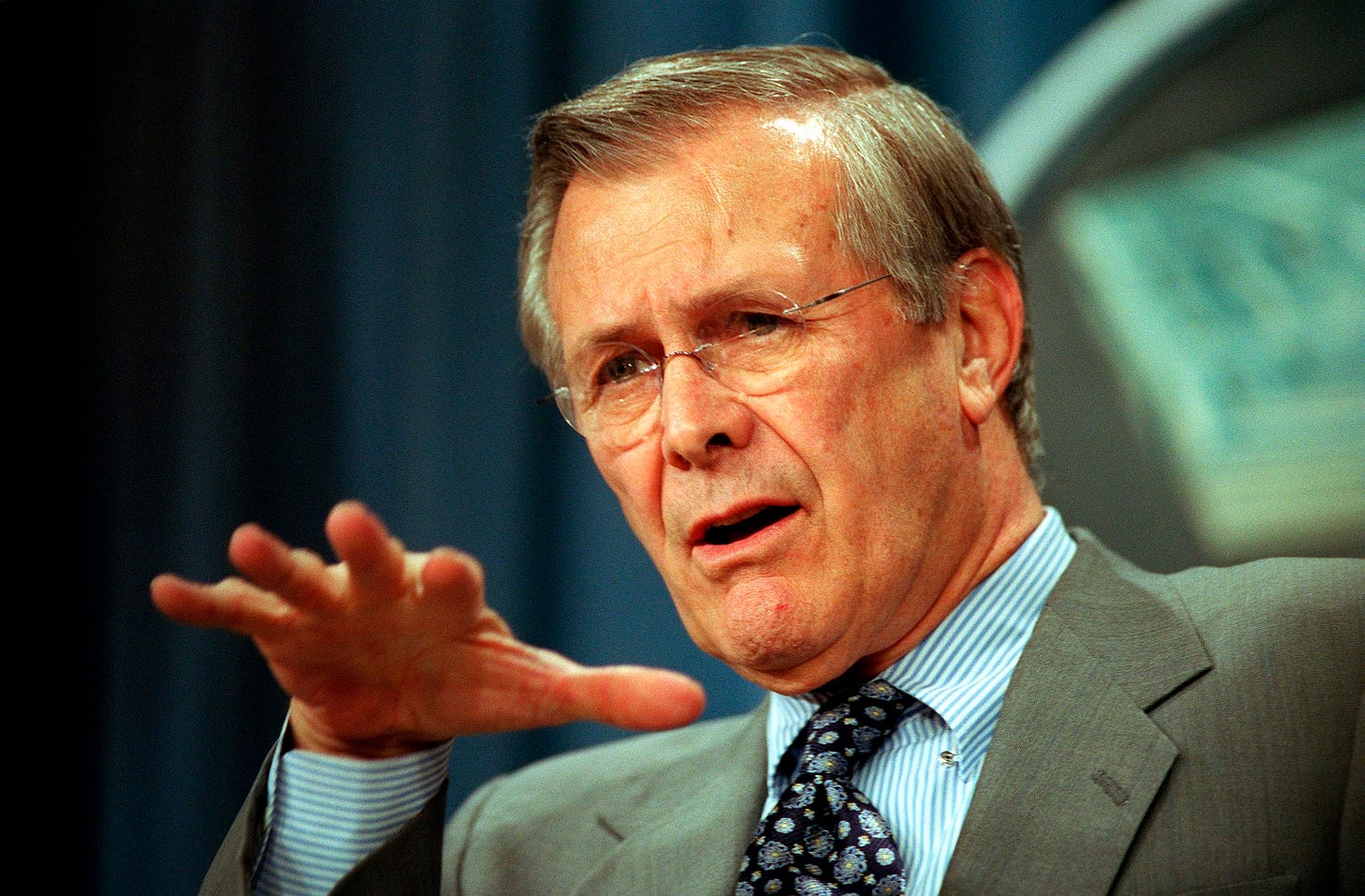

Donald Rumsfeld was already a well-known figure before he became George W. Bush’s Secretary of Defense (the second time he held the office), but the events of his last years of public service have largely eclipsed memory of his prior career. He’s probably best remembered, though, not for any office he held or any decision he made, but for an epistemological taxonomy:

Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.

It’s not a bad insight as far as it goes. The things most likely to surprise you are things you not only didn’t know but didn’t realize you didn’t know. But Rumsfeld’s litany leaves out one iteration, the iteration that I would argue was most important in explaining the catastrophe of the Iraq War: the unknown knowns.

That phrase became the title of Errol Morris’s documentary about Rumsfeld, made up of interviews with its subject, and its meaning changes from the beginning to the end of the film. Initially, Rumsfeld himself defines unknown knowns as things we could have anticipated but didn't, because of a failure of imagination or initiative. 9-11 itself could be considered a good example of this: Had we been looking squarely at the information available, we could have known that something was coming, but we didn’t look, and so we didn’t know.

Taking that as the meaning, the lesson is to dig harder, look closer, make sure that we really know everything that we ought to know. But here’s the thing: after 9-11, that’s what America started doing. At Vice President Dick Cheney’s initiative, all kinds of raw intelligence started getting stovepiped up, under the mistaken impression that this was making what we knew more visible to the decision makers who needed to know it. But that wasn’t increasing our knowledge. On the contrary: it was only helping us accumulate another kind of unknown known.

But by the end of the movie, Rumsfeld has transformed the phrase to mean something different, and more apposite. Unknown knowns are things we believe we know, but don’t actually know. They are false beliefs that we have confused with knowledge. These absolutely abounded in the run-up to Iraq: the conviction that Saddam Hussein had an active nuclear program; that Iraqi intelligence had been involved in 9-11; that there was some kind of “Axis of Evil” encompassing Iraq, Iran and North Korea; most grandly, that Iraq had all the ingredients necessary to become a thriving democracy, needing only to be liberated from its oppressive government for it to become a reliable and valuable American ally.

The American government did not know any of these things. It’s not just that none of them were true; none of them were close to true. Moreover, they were readily refuted by other things that not only could have been but were known: evidence from the inspections about the state of the Iraqi weapons program; understanding of Iraqi culture and the likely state of a society that had been governed in a totalitarian fashion for decades. There is a lot that our government knew, but the people making decisions didn’t want to know it, and so it was unknown. Meanwhile evidence of one kind or another could be marshaled for all of the false propositions they wanted to believe, and treated as confirmation of what was known. It’s a method practically guaranteed to lead to catastrophic decision making, which is precisely what it did. And Rumsfeld was right there at the heart of it.

How could that be? Given his long experience and the attendant accumulated wisdom, how could he not have known that the process was catastrophic? The most likely answer is that he wasn’t all that concerned with the question. Intelligence wasn’t important to Rumsfeld primarily for knowing the right answer; nobody who could write a memo like this one to “the fucking stupidest guy on the face of the earth” could possibly have cared about getting the right answer to anything:

Intelligence was useful, rather, as a tool for winning the high-stakes game of bureaucratic infighting that Rumsfeld loved, and played so well. If a particular piece of information—whatever its provenance or reliability—would help him get what he wanted, then it was useful to “know.” I have no idea if he had any genuine convictions about Iraq, in the fashion that, say, Paul Wolfowitz did, or indeed if he had any genuine convictions about anything. It strikes me as highly likely that he saw the Iraq War primarily as a mechanism for testing out certain theories he had about how to make American war-fighting more nimble, and that he was pleased with the results of that test when we quickly shattered the Iraqi army and took Baghdad with a much smaller force than he had been told would be necessary. If the war proved a subsequent disaster, he no doubt saw that as someone else’s department—and could point to the memos that proved it.

Rumsfeld, then, may have never really thought he knew the things he should have known he didn’t know. Indeed, he probably made it a point not to know things like that. But plenty of his colleagues were not so clever. From the top down, the Bush administration was full of people who knew things that just weren’t so, and refused to know things that were well-known but unpalatable, and made decisions accordingly.

I wish I could say that Rumsfeld’s epitaph was to have taught us all a lesson. I fear that we are too stubborn to learn it, because we figure we know all that already.