Remember this guy?

I’m old enough to remember, back at the beginning of the pandemic, the original purposes of placing severe restrictions on economic and social activity. The reasons were threefold. First, we needed to protect the most vulnerable, particularly the elderly, who had a very high death rate from the virus. Second, we needed to preserve the medical system, which could easily be overwhelmed if the number of cases grew too rapidly, leading to many people dying who could otherwise have been saved. Finally, we were buying time, to learn more about the virus and how to treat it, to get to warmer weather that would permit us to move outside, and most ambitiously, to ramp up a massive testing-and-tracing infrastructure that, once case loads had been crushed very low, could nip future outbreaks in the bud. Once those goals were accomplished, we were supposed to relax the vast majority of restrictions and back to something close to normal life.

We never stood up that testing-and-tracing infrastructure, and we also never crushed case loads low enough for us to replicate the South Korean success story had we put such an infrastructure in place. Nearly a year ago, I was already saying that America had lost the battle with COVID-19, and the time had come to make a plan for failure: to figure out how what social changes we needed to make to be able to get back to a mostly functional life (in particular: getting schools open), and live with the virus while still achieving the first and second goals of protecting the most vulnerable and preserving the medical system from being overwhelmed.

Well, we never really did that either. Schools in much of the country did not open last fall, even though it was clearly possible to do so safely in the sense of not overwhelming the health care system or sending a scythe through the ranks of the elderly. Nonetheless, much of the country did go back to whatever semblance of normal life they could cobble together, shopping, eating out, gathering with friends and family. That incoherent response partly reflected the diffuse nature of authority in a federal system—local authorities could close schools but not bail out restaurants, so the closed schools but let restaurants open; federal authorities, meanwhile, could bail out restaurants but not open schools. But it also reflected a shifting of goal posts, from a public health mindset to a liability mindset. Rather than saying, “will this restriction make a big difference in the context of how everyone is behaving,” public authorities shifted to “are we putting anyone at risk without their consent by removing this restriction?” With the goal posts duly moved, one could squint and justify not opening the schools on the grounds that doing so would be “putting kids and their families at risk,” but opening restaurants on the grounds that “nobody is making you go out to eat,” even though that was an insane combination from the perspective of the common good.

Then, we did something I didn’t expect (because I am not plugged into the world of vaccine research): we developed extraordinarily effective vaccines in record time. That miracle arrived just as the worst wave of the pandemic was gathering strength, and just as new and more contagious variants meant that an even bigger wave might be following right behind. Initially it seemed it might have come too late, as cases and deaths surged while the vaccine rollout sputtered. But now the peak of the winter wave is more than three months in the past, and the vaccine rollout has—notwithstanding the recent slowdown or the hesitancy in certain populations—proved a great success. More than half of the adult population has received at least one shot, and more than 80% of the over-65 population has done similarly. With a little elbow grease, we should be able to reach Israeli levels of vaccine penetration by the end of the month.

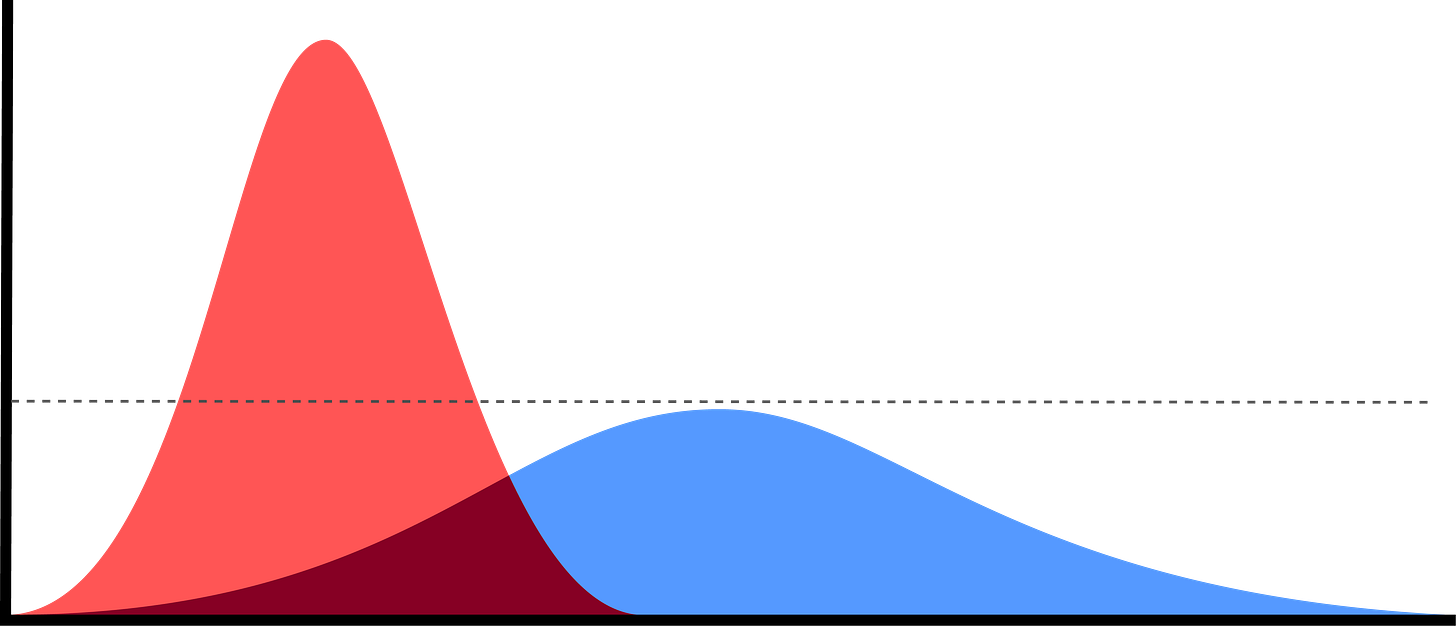

And yet, for a lot of people I know, that has prompted not so much enthusiasm for the reopening that is happening, but a further moving of goalposts—to the goal of eliminating COVID entirely from our lives. And while I understand how tantalizing it must be to think, if only everyone got vaccinated then we could actually win this thing outright, in fact this is a refusal to accept victory. We don’t need to move the goalposts further out. Rather, it’s time—way past time—to move the goalposts back.

That, I think, is the actual message of this article in The New York Times with the troubling headline “Reaching ‘Herd Immunity’ Is Unlikely in the U.S., Experts Now Believe.” But you almost can’t tell because of the way the piece is framed. It’s true that “herd immunity” in the sense of enough people being immune that the virus simply dies out is very unlikely to happen at this point. That’s partly because not enough people will get vaccinated, and partly because most of the world is far behind America in the race to vaccinate their populations, and the virus is continually mutating in the populations where it is still circulating widely. So COVID-19 will not be eradicated outright; instead we may well need periodic booster shots to keep us well-protected against new strains that pop up, and some people will indeed get quite sick and even die every year even so.

But that is a completely normal approach to managing disease. And the real point of the article, I think, is to remind people of that fact. Here’s the key section:

If the herd immunity threshold is not attainable, what matters most is the rate of hospitalizations and deaths after pandemic restrictions are relaxed, experts believe.

By focusing on vaccinating the most vulnerable, the United States has already brought those numbers down sharply. If the vaccination levels of that group continue to rise, the expectation is that over time the coronavirus may become seasonal, like the flu, and affect mostly the young and healthy.

“What we want to do at the very least is get to a point where we have just really sporadic little flare-ups,” said Carl Bergstrom, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Washington in Seattle. “That would be a very sensible target in this country where we have an excellent vaccine and the ability to deliver it.”

Protecting the most-vulnerable, preserving the health care system from being overwhelmed, and getting to the point where there are just sporadic little flare-ups were always the goals, though. Or, rather, those were the goals at the beginning of the pandemic, and they were achievable. I wish we had achieved them earlier, and saved hundreds of thousands of lives, as South Korea did. If we’re belatedly in prospect of achieving them through an effective vaccination campaign, I’ll take it. But vaccination as a strategy for wiping out the virus entirely via herd immunity is another case of moving the goalposts—and this time the goal isn’t really even possible, because the United States cannot achieve that goal unless the entire world achieves that goal, which isn’t going to happen for years, if ever.

As a society, we are moving quickly toward full reopening, but an influential segment of society has internalized those goalpost shifts—from the original goals to much more sweeping ones, and from a public-health mindset rooted in realism about human behavior to a zero-risk mindset rooted in liability—and is digging in with pockets of resistance. I worry about that, because I see it in my own little world, and the damage it is doing to communal institutions, places like schools and houses of worship. Pushing back, and returning to what the goals were always supposed to be may require some degree of assertion on the part of those who understand that fact, both political leaders and private citizens. It means threading the needle of respecting different people’s risk-tolerances, and accommodating those who are more conservative as much as possible in their conduct of their own lives—but being firm that communal needs are not subordinated to the most conservative segment of the population, but only to the communal public health objectives that we had from the beginning, objectives that are perfectly consistent with a substantial relaxation of restrictions.

I hope I’m wrong, and that much of this resistance simply evaporates as the surrounding society reopens and cases and deaths continue to fall. Even better, inasmuch as it is an impulse rooted in a desire to be righteous, I hope it gets channeled in a different direction, into pushing for greater efforts by the government to vaccinate the world, and into empathetic person-to-person outreach to allay the concerns of and more generally assist those who are vaccine-hesitant. Those jobs don’t become less important as the pandemic recedes and we reopen; they become more so. But we can’t achieve them simply by waiting and abstaining.