The Greenspan Put Was Really a China Put

Without China, bailing out investors would have been inflationary all along

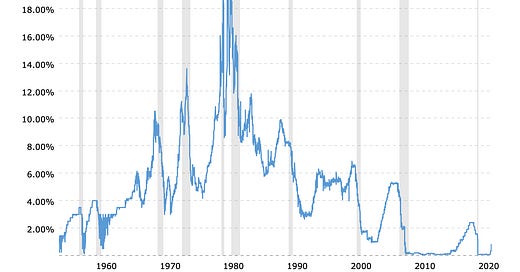

Evolution of the Federal Funds Rate from William McChesney Martin to Jerome Powell (from macrotrends.net)

Noah Smith has a worthwhile piece up on this website about the so-called “Greenspan Put” and how it has finally expired. I was planning on writing about a related subject this week (inflation and what the Fed is going to do about it) but having seen his piece it makes sense to start there and use his framing.

To recap what Smith says (and it’s worth reading his whole piece for a fuller discussion), then-Fed chair Alan Greenspan responded effectively to a series of market crises in a way that led investors to describe him as offering them a “put option” on their investments. A put option is a right to sell at a specified price on a future date; if you own a put option on your investment, you know that the worst your investment will do is the “strike price” of the put, because you can always sell at that price in a pinch. Having less risk of loss will encourage you to take more risk for gain, and thus the expectation that the Fed would bail out investors arguably encouraged excessive risk-taking, leading to worse crises.

Now, of course, the stock market is dropping and the Fed is nonetheless raising rates rather than dropping them. The Fed is appropriately prioritizing fighting inflation, and so investors can’t expect the Fed to bail them out like they did in prior stock market drops. So the put has expired—downside risk is back in the market, and investors should expect continued losses across asset classes.

What’s interesting to me about the whole notion of a Greenspan Put is that the era when Greenspan got his reputation for wizardry was a largely tranquil one during which Greenspan didn’t have to do very much. He dropped rates slightly in reaction to the 1987 stock market crash, but as soon as it was clear the real economy wasn’t suffering rates resumed their upward climb. He dropped rates much more substantially in response to the recession that followed the Savings and Loan crisis, but he hiked rates with alacrity in the early years of Bill Clinton’s presidency as the economy emerged from that slump. I remember Democrats complaining at the time that he was taking the punch bowl away just as the party got going, and blaming the backup in rates both for the need to focus on deficit reduction and for the GOP takeover of the House of Representatives in 1994. But Greenspan didn’t control the bond market, and his behavior during this period looks like completely normal Fed behavior in response to macroeconomic conditions that, in retrospect, were quite mild.

The long bull market that started in 1994 and ran through to the 2000 dot-com bust featured almost no movement in the Fed funds rate. There were financial hiccups during this period, but by far their greatest impact was felt abroad, in Southeast Asia and Russia. In America, they really were blips, and the Fed didn’t actually need to do that much to stop them from spawning financial contagion. Greenspan may have been lionized in the financial press as the engineer of stable growth with low inflation, but it’s probably more accurate to say that he benefited, just as President Clinton did, from a confluence of positive macroeconomic factors not of his own making. If the “Greenspan Put” existed, then, it was a feature of market psychology first and foremost.

Which brings us to the dot-com bubble and its aftermath. Was that speculative frenzy driven by a too-accommodating Fed? I’ve always been skeptical of that contention, because unlike, say, the housing bubble of the mid-2000s or the stock market bubble of the late 1920s, it wasn’t characterized by excessive leverage. Greenspan himself professed agnosticism about the size, scope or even the reality of the bubble while it was inflating, and that probably was the appropriate attitude for the Fed to take.

But if the bubble itself wasn’t debt-driven, and therefore arguably wasn’t a Fed creation, then why did the Fed respond so aggressively to its bursting? It was reasonable to assume that the massive drop in the stock market—which the Fed did not prevent!—would feed back into a real recession, and that’s precisely what happened. So in the wake of the dot-com bust, the Fed became very accommodating, and stayed accommodating, arguably fueling the debt-driven housing bubble that did far more damage to the global economy than the dot-com bubble ever could have.

Why did the Fed behave this way? Persistently low interest rates were justified because inflation remained quiescent, unemployment modestly elevated, and growth relatively anemic. But in retrospect, it looks like the big disinflationary engine and the big provider of cheap leverage were one and the same: the rapid integration of America’s economy with China. Permanent normal trading relations facilitated a massive expansion of cross-Pacific trade, and China recycled its large trade surpluses by purchasing American government debt in large quantities, thereby facilitating a fiscal expansion that mostly didn’t go into greater productive capacity. You could describe the integration of China into the world economy, and with America specifically, as a massive positive supply shock, like the discovery of a huge quantity of precious metals. America felt wealthier, but not because it was able to generate more wealth—on the contrary, productivity growth was slow in the 2000s, and probably looked higher than it even was because of the way that offshoring can artificially inflate productivity statistics. The Fed’s accommodative stance was underwritten not by a virtuous cycle in the domestic economy but by close to its opposite.

Now, supply shocks, positive or negative, fall outside the scope of the Fed’s capacity to manage, so inasmuch as the Fed largely sidestepped the question of why inflation remained quiescent even as it became extremely accommodative, arguably it was only doing its job. Certainly, in the wake of the much more serious crisis that followed the housing bubble, the Fed acted appropriately in pulling out all stops to boost aggregate demand and prevent the world from falling into an outright repeat of the Great Depression. That overriding concern did and should have eclipsed everything else.

But now we’re in a very different world. America is well along in the process of unwinding its economic integration with China, Chinese savings are no longer financing American fiscal expansion, and in the wake of the unprecedented sanctions against Russia over the invasion of Ukraine its reasonable to expect China—and India, Brazil and numerous other countries—to seek ways to further separate themselves from the Western financial system to the extent they can. That negative supply shock, far more than oil prices or chip shortages or the positive demand shock from the fiscal response to the pandemic, is, I suspect, the biggest background reason why the Fed’s room for maneuver has shrunk. The Fed never had the capacity to write a put in the fashion that some commentators imagine. Without the China shock, a Fed strategy that tried to bail out investors—which is not, I reiterate, what the Fed was really trying to do, but which arguably was a side effect of the Fed just doing its job—would have triggered inflation much more quickly.

All of which means, in a nutshell, that without a new positive supply shock, we’re likely in for a world of persistently higher rates than most people currently in the markets have seen, and also a world of higher inflation. The Fed might well get inflation expectations under control using the tools at its disposal, but the equilibrium combination of inflation and unemployment is likely higher now than it was in, say, 1999 or 2006.

The Fed can’t do anything about the supply side; that’s a matter for elected policymakers to tackle. So our politics needs to reorient around finding ways to improve things on the supply side—and, more specifically and in contrast to the 2000s, ways that actually improve the productive capacity of the real domestic economy.

"Chinese savings are no longer financing American fiscal expansion, and in the wake of the unprecedented sanctions against Russia over the invasion of Ukraine its reasonable to expect China—and India, Brazil and numerous other countries—to seek ways to further separate themselves from the Western financial system to the extent they can." So where are China, India, & Brazil parking their funds outside the Western financial system? Commodities including rare earth minerals & both base & precious metals, crypto currencies, real estate, fine art?