The Field or the Players?

Remembering the importance of the map to the 2022 election results

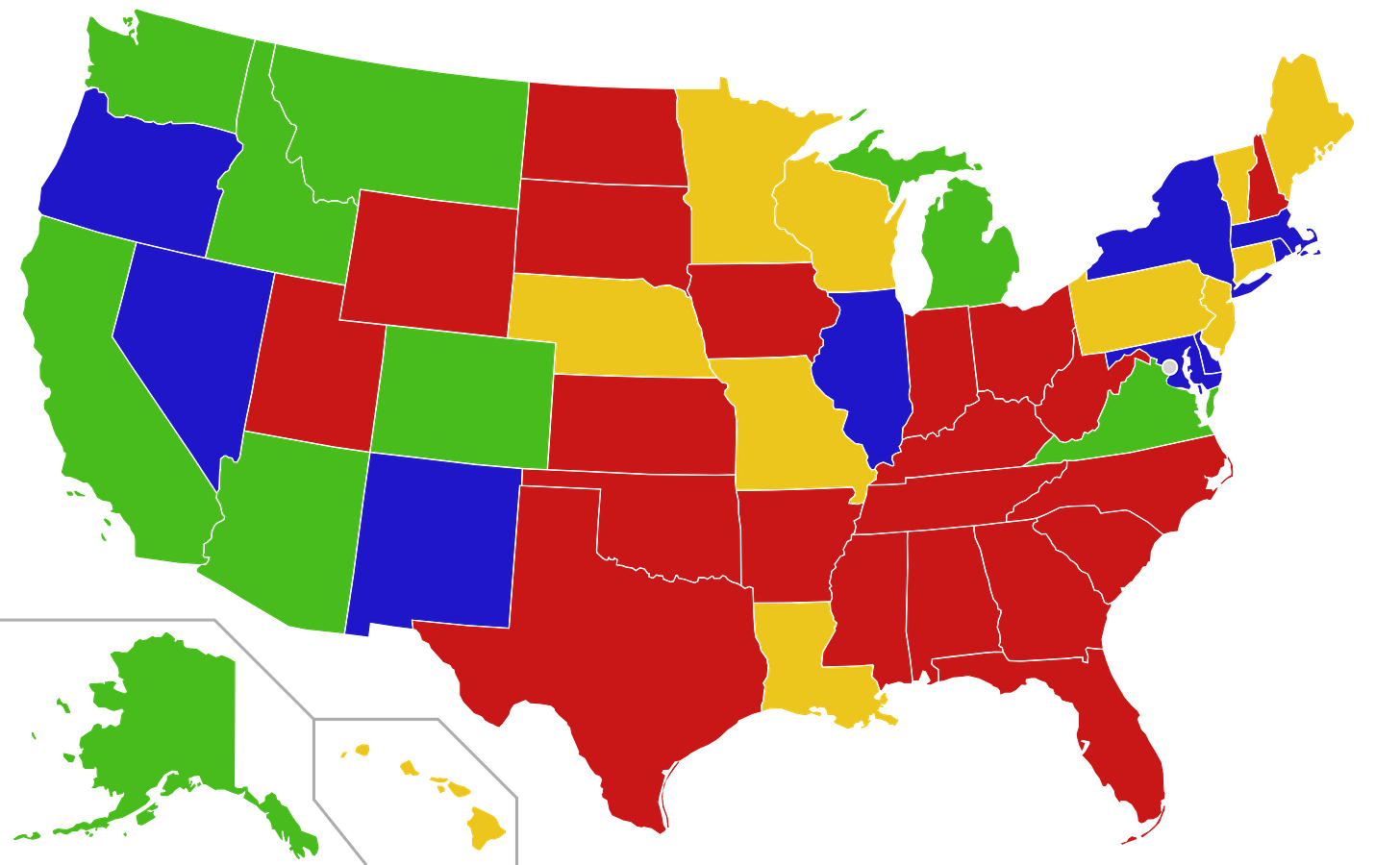

Partisan control of state legislative redistricting after the 2020 elections: red is Republican-controlled, blue Democratic-controlled, yellow split control and green controlled by an independent commission.

Back in early 2021, if you looked at recent election results, then looked at the map of the 2022 election, and were then asked to predict the results of the 2022 election, you might have reasoned something like the following.

Well, you might say, the Senate now has a regular bias against the Democrats because it substantially over-represents rural areas, and these have been trending Republican for some time. On the other hand, Republicans are on the defensive with this map in particular because 21 Republican-held seats are contested versus only 14 Democratic-held seats. On the third hand, of course, mid-term elections generally go against the incumbent party, because they are viewed as a referendum on that party’s performance and also feature a thermostatic reaction to change of any kind. But on the fourth hand, in the 2018 midterm election the Senate map dominated over thermostatic reaction, and the 2020 election was a near-tie despite a relatively-favorable map. Knowing nothing about the political environment in 2022, then, you might have concluded that the battle for the Senate would be close-fought.

Meanwhile, in the House, you might note that there was a more pronounced thermostatic reaction in 2018, with Democrats winning over 53% of the House popular vote and gaining 41 seats. A similar swing in the opposite direction would devastate the Democratic majority. But you might have also noted that in the 2020 election the Democrats lost seats—unusually for a party with a winning presidential candidate at the top of the ticket—meaning that the baseline from which to swing was already set lower. Finally, the map, which had been significantly biased against Democrats since the 2010 redistricting, was likely to grow considerably more favorable after the 2020 redistricting, which would be less dominated by Republican-controlled legislatures. So, once again, knowing nothing about the political environment in 2022, you might have concluded that the battle for the House would be close-fought.

As we now know, if you’d made your predictions on the foregoing basis, you would have been right. That should tell us something about how much the real story of the 2022 elections is about the maps. Sometimes the field matters more than either the players or how they play the game.

That’s not to say that nothing else mattered. The thermostatic reaction in 2022 was more modest than in 2018 or 2010. In 2020, the Democrats won 50.8% of the House popular vote versus 47.7% for the Republicans, a spread of just over 3%, and won a bare majority of 222 seats. With elegant symmetry, the Republicans won in 2022 with 51.4% of the popular vote versus 47.1% for the Democrats, a spread of just over 4%, and look likely to win a similarly bare majority. The spread between the two parties’ popular vote in 2010 and 2018, by contrast, was 6.8% and 8.6% respectively—so whether because abortion was on the ballot or because Republicans were viewed as threats to democracy or simply because the actually-enacted Biden agenda is more popular than many political observers realized, Democrats were able to hold Republicans to a wave roughly half the size of recent midterm reactions. That’s a testament to how well the played the game.

But in 2016, Republicans only won the House popular vote by 1%, and won a solid (but reduced) majority of 241 seats. And in 2012 they lost the popular vote by 1%, and won a majority of 234 seats. If both parties had put up similar aggregate numbers this year, but with the vote distributed as it currently is, the Democrats would have significantly padded their majority. That is the effect of different maps, both in terms of redistricting and the decreased efficiency of the Republican vote for reasons independent of redistricting.

You can see the effect of the maps state by state. Florida, controlled entirely by Republicans, pushed through an extremely aggressive partisan redistricting plan, and Republicans gained five seats. New York attempted to push through a similarly partisan redistricting in spite of a constitutional amendment mandating a more independent and bipartisan process, and wound up getting rebuked by the courts, then made further blunders in response to the court’s rebuke. The result was a much fairer map, and a net Republican gain of four seats. By contrast, in Illinois Democrats were able to push through a partisan gerrymander that netted them a three-seat gain, and in Michigan an independent commission resulted in a fairer map than the 2010 Republican gerrymander, which was part of what enabled Democrats to hold their own in the House delegation despite the dynamics of a midterm election. (Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s coattails probably didn’t hurt either.) In Texas, meanwhile, where maps were redrawn on a partisan basis, the Republicans focused on shoring up their existing majority rather than trying to catch a wave and pad it, resulting in another draw with gains for neither party in the House delegation.

Even fair maps that are drawn without partisan bias can wind up with a partisan slant simply because coalitions can be distributed more or less efficiently. But whether by accident or by design, maps matter—and they mattered a lot in 2022.

As for the Senate, where the map never changes unless we start breaking up our largest states, the overwhelming majority of the 35 seats up for election were tilted strongly toward one party or another from the get-go. Nonetheless, the prospects of a real wave in the Senate under the right conditions were real. Democrats had real vulnerabilities not only in Nevada, Arizona and Georgia, but also in New Hampshire, Colorado and maybe even Washington. Republicans had vulnerabilities not only in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and North Carolina but also in Ohio, Florida and maybe even Missouri. A GOP tidal wave could have netted them as many as six seats. A Democratic tidal wave—extremely unlikely under the circumstances—could have netted them the same.

Six-seat swings used to be fairly normal. The 2014 election netted the GOP nine new Senate seats. The 2010 netted them six. The Democrats gained six seats in 2006 and eight more in 2008. But swings like that have become far less common as more and more states have developed pronounced partisan leans. Only two seats flipped in 2016, two on net in 2018, and three on net in 2020. And the 2022 results suggest that fewer states are truly contestable than ever. Democrats fielded excellent candidates in Florida and Ohio but lost decisively in both states. Republicans, meanwhile, performed worse in Colorado and New Hampshire than they did in 2016.

It is striking the way, over the past 4 Senate cycles, the same states keep coming around as potential toss-ups. Six seats were won with less than 52% of the vote in 2022: Arizona, Georgia, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. (I don’t count Alaska because it’s an intra-Republican contest.) All featured similarly close races in at least one other recent cycle and three of them—Arizona, Nevada and North Carolina and Arizona—featured similarly-close contests in every prior cycle back to 2016. Fully half of the contests won with less than 52% of the vote over the past four Senate cycles were in those six states, and there were fewer such close contests in 2022 than in each of the prior three cycles.

My old editor Dan McCarthy argues in his latest column at The Spectator that 2022 was just a good election for incumbents of all political stripes. But I don’t think that’s the case. Democratic and Republican incumbents improved on their prior results in 2022 in states like Colorado and Florida, New Hampshire and Missouri, that have been trending generally toward one party and away from the other. Meanwhile, Democratic incumbents in Georgia and Nevada, and Republican incumbents in North Carolina and Wisconsin, did about the same in 2022 that they did when last they ran. Which is why I keep coming back to the map. While on the House side 2022’s results provide evidence that the Democrats may now have a modest advantage in winning the chamber, the Senate results of 2022 show nothing similar. If anything, they show the opposite: that the map may be hardening. But expanding the map—which Democrats tried to do aggressively in 2020 with barely any success—is essential to the Democrats’ long-term hopes of remaining competitive in the upper chamber.

It’s also essential to the future of our democracy. Because to the extent the map rules, to that same extent the people don’t.

Does your old boss Daniel McCarthy always bang out his columns without rereading or editing?

"not a single sitting senator or governor lost."

Tell Steve Sisolak that. He conceded on November 11, rather long before the Nov 14 date of McCarthy's column.

Maybe I am supposed to take McCarthy's columns seriously but not literally?