The Autobiography of an Idea

Debating the nature of American nationhood is the most American thing of all

Almost in passing during his speech on Wednesday night, President Biden made a statement that drew a quick rejoinder from the right.

Biden:

America is an idea – unique in the world. We are all created equal. It’s who we are. We cannot walk away from that principle.

Rejoinder:

To which I responded:

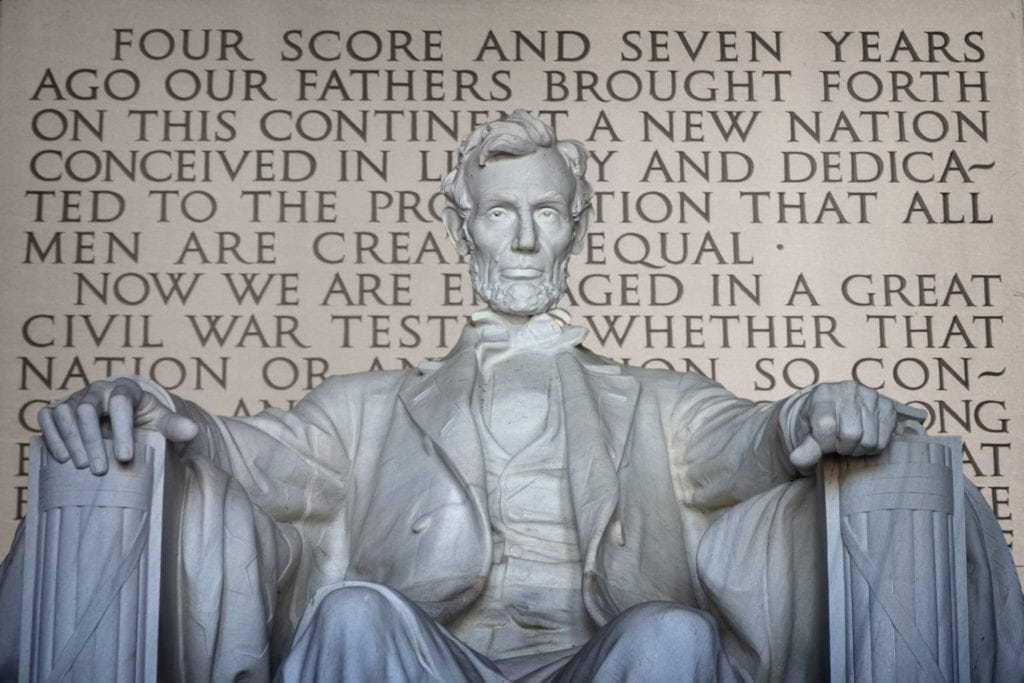

Twitter is a glib medium, so I’d like to take this opportunity to expand on what I meant by quoting President Lincoln in response to Lowry.

The word, “nation” comes from a Latin root for “birth” and in that language its original usage was derogatory—it meant “foreigner” or “ethnic” in contradistinction to Roman citizens. At its origins, then, the “national” was opposed to the “civic.” It is used similarly in translations of the Hebrew Bible, where “nations” are various peoples descending along different lines from one or the other of Noah’s sons, and are grouped collectively in contrast to the People of Israel who, while also tracing a common ancestry, are constituted as a people by virtue of the covenant. In medieval French usage, meanwhile, at the University of Paris, the word was applied to groups of students who came there from across Europe—the “French” nation, which included students from Spain and Italy; the “German” nation, which included students from England; the “Picard” nation which included the Dutch; and so forth. (An analogy might be made to the way that, on contemporary American campuses, students are encouraged to sort themselves into racial and ethnic affinity groups, groups that may bear only a limited relationship to either common ancestry or common experience.) Once again, “nation” was something that defined your group in contradistinction to a common project that transcends group identity.

(I’m cribbing in the foregoing from Liah Greenfeld’s book, Nationalism: Five Roads to Modernity, which is worth a read.)

Obviously that’s not quite how we use the word today. “Nation” has, for us, come to mean a sovereign political community; in that sense, we’ve come to identify the civic with the national rather than oppose them to one another. By the same token we’ve also redefined the national so as not necessarily to imply a myth of common ancestry. But even in a case like Scotland, where there is no distinct language, no political subjugation, and an affirmative rejection of an identity based on common ancestry, “nationalism” still refers to an ideology of belonging and solidarity, of something shared that defines the meaning of common membership in the community, and therefore of the community itself.

That’s the sense in which Biden used the phrase “America is an idea.” Obviously, America isn’t merely an idea—it’s a particular place, a particular community. But what makes it a community is not a myth of common ancestry, which we cannot embrace because it is too obviously false, but a common idea. We are a “creedal nation,” or a “nation with the soul of a church” as Chesterton put it. Lincoln quoted Jefferson to the same effect: we are a nation because we are dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. This answer, then, is a longstanding one, and perhaps the most familiar to Americans since it became the dominant framework in the post-World War II era. Indeed, by this point in time it is hard for a lot of people to see any conception of nationalism other than the creedal conception as anything but atavistic and deeply un-American.

But as Sam Goldman delineates well in his short, compelling study, After Nationalism, that creedal idea has waxed and waned through American history in competition with other conceptions of American nationhood: as derived from a foundational covenant, for one crucial example, or through the metaphor of the crucible or melting-pot that transforms diverse nations into a single substance, for another. What all these conceptions have in common, though, is that they are ideas. Compared to the myth of common ancestry, they are abstract, cerebral, metaphoric. They are just not all the same idea.

Goldman’s overarching argument in the book is that none of these conceptions has ever proved entirely successful—the Puritan covenantal idea, for example, from which we get the metaphor of the “city on a hill,” became identified with a New England elite that was never really sufficiently dominant to define America as a whole, though it has had a surprisingly long afterlife since that elite’s precipitous decline. Therefore, he concludes, we should perhaps abandon the search and learn to live in a post-national world. I’m not convinced that’s possible, or that it would be desirable if so. My sense, rather, is that just as Eisenhower said that “our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don't care what it is,” America can’t be made sense of as a nation except in terms of being an idea—but we’ve never really agreed and probably never will agree on just what that idea is.

The question ultimately posed by America is how long we can go on that way. That’s what I wanted to drive home by quoting the second sentence of the Gettysburg Address as well as the first. Lincoln understood that, inasmuch as America was defined by a creed, it was dedicated to a proposition, not a revealed truth; he had the tragic understanding that even fervent dedication was insufficient to assure that any such proposition would be proved true. That’s a sense our civic believers would do well to recover, even as their critics would do well to recognize that they are stuck being part of the same civic experiment as the rest of us Americans, even if they have lost their faith in it, or in us.

A few additional thoughts on this topic.

It’s particularly funny that Biden got nationalist pushback from Lowry for calling America an idea because his speech in general was quite a nationalistic one, inasmuch as its primary touchstones were building national solidarity and building national capacity. I often wonder what self-styled nationalists of the right even mean by nationalism apart from the totemic qualities of the word itself. Who, in this debate, is really devoted more to an idea, and who to the national community that actually exists?

What’s more important, I think, is the context in which Biden placed the phrase: not in the part of the speech dedicated to building up the nation, but in the part of the speech dedicated to the defense of human rights abroad. I don’t think that’s accidental. Creedalism is a fighting faith; its two periods of dominance were the Civil War era through Reconstruction and World War II through the Cold War. One of the most notable points of continuity between the Trump and Biden administrations, and of agreement between Biden and many of his critics on the right, is the centrality of the Chinese challenge in the coming decades. I think it’s worth thinking carefully about how our conception of America’s nationhood might help or hinder us in meeting that challenge, but also how that conception might push us towards or help us avoid unnecessary and potentially catastrophic conflict along the way.

Finally, I can’t help but think about the question of “is America an idea” in the context of the ruckus of the 1619 Project and its possible inclusion as a central element in American school curricula.

There’s a lot to debate about that project in terms of the quality of its scholarship, but its central purpose is mythic rather than scholarly—and I don’t mean that in a negative sense, because promulgation of myth is as much a part of education as is teaching the critical skills necessary to see through myth and dismantle it. A key aim of the 1619 Project is to change how Americans understand ourselves as a nation, and I would argue specifically to counter the understanding of America as an idea with an understanding that emphasizes common ancestry—but including the part of that ancestry that has historically been repressed and denied. If, after all, America is not essentially an idea, then we can’t say that our founding was in 1620, or 1776, or 1787, or 1865; our founding was when the founding population arrived from which we are derived, and Black slaves must be understood as conceptually equal contributors to that founding from the beginning. In that sense, just as opposition to the project has made strange bedfellows among traditional Republican politicians, centrist pundits and left-wing socialists, I wonder whether there isn’t a subterranean sympathy between critics of the myth of the American idea on both the right and the left like Sam Goldman and Nikole Hannah-Jones.