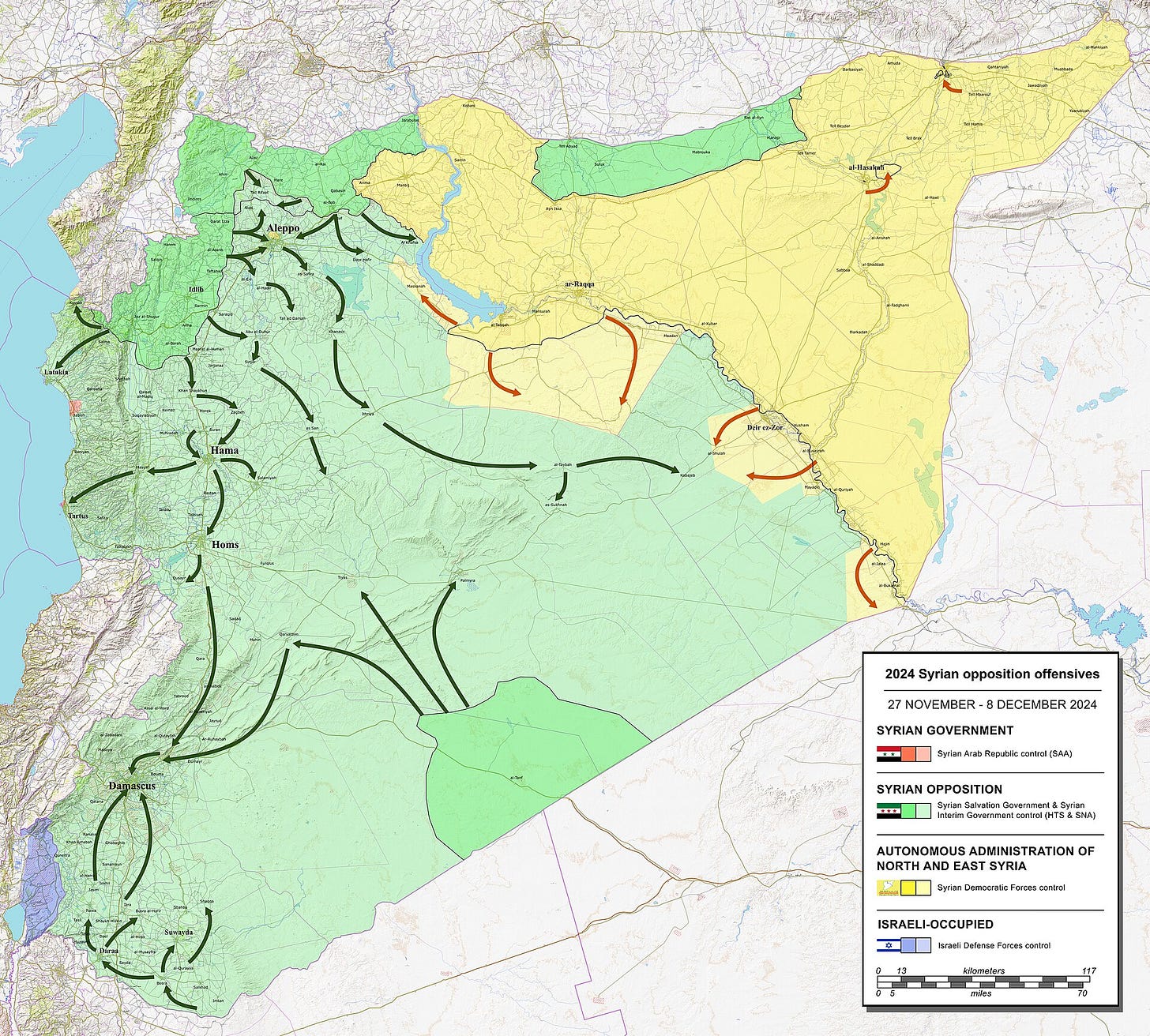

Map of Syrian opposition offensives, November 27th to December 8th, 2024

I write more than occasionally about foreign policy, and often when I do it’s a piece about the Middle East, so while I’m certainly no expert, I’m nonetheless feeling quite disappointed in myself for not having any idea that the Syrian civil war was heating up again, nor being in any way prepared for the possibility that the al-Assad regime could collapse like a house of cards. When the United States withdrew from Afghanistan, virtually all informed observers assumed that the result would be the entry of the Taliban into the government, whether through a negotiated agreement or by violent takeover; the only surprise was just how incredibly quickly it all unraveled. The events in Syria remind me of that, except that I had no inkling it was coming at all.

So take any lessons I’m drawing from those events with a grain of salt. I didn’t see this coming; why should I have any idea what happens next? Nonetheless, here are my salt-sprinkled initial thoughts.

The change of regime is obviously good news for Turkey and bad news for Iran. Turkey provided the most important support to the dominant rebel faction, and should emerge as the new regime’s most important patron. I would expect the new regime to reward them by giving them carte blanche to consolidate Turkey’s buffer zone in northern Syria, more effectively cutting the PKK off from the Kurdish areas in Syria and Iraq. But beyond that, and getting Turkish firms a lead role in reconstruction and trade, I don’t have any real idea what the Turkish government wants. I imagine we’ll find out, but until we do we can’t really know what the largest implications of the war are.

For example: will Turkey press its new advantage versus Iran, its most important regional competitor? The fall of al-Assad means Iran has lost its only actual state client, and through it may have also lost the conduit it used to funnel arms and other support to its most important non-state client, Hezbollah. Coming on the heels of Israel’s crushing destruction of Hamas, its degradation of Hezbollah, and its missile, drone and air war with Iran itself, the fall of Syria to Sunni Islamists looks like yet another devastating blow to Iran’s ambitions. But is Turkey interested in Iran’s outright defeat? Or would it be satisfied merely to check Iran’s ambitions and see Iran moderate its foreign policy?

It’s a shift that would make a lot of sense for Iran given its recent losses. Turkey’s hostility to Iran—and to Hezbollah, for that matter—is largely due to Iran’s own aggressive behavior. Could Iran’s retreat from Syria presage a more defensive foreign policy generally? Could Hezbollah itself revert to being the defender of Shiite interests within Lebanon, and of Lebanese sovereignty against Israel? I don’t see how anyone can know for sure, but if Iran did moderate it would make a lot of sense for Turkey to mend fences with it, however much that would frustrate allies like the United States. I note in that regard that both Turkey and Iran were and are supporters of the Sunni Islamist group Hamas, so I don’t see why in principle they couldn’t cooperate on the matter of Hezbollah, provided Turkey and Iran had themselves worked out a modus vivendi.

Of course, Iran might not have the freedom internally simply to do what makes rational sense for the regime in terms of defending its interests. Ever since Iran’s proxy war with Israel escalated to direct tit-for-tat blows, I’ve wondered at the possible effect on the stability of its regime. Iranians should logically be far more willing to see Palestinians and Lebanese die for Iranian interests than to see Iranians die for theirs. But now that Iran has—sensibly—abandoned its Syrian client in its hour of need, the regime has to worry about discontent from its most ideological supporters in the Revolutionary Guard Corps. If Iran proves unable to accommodate itself to its weakened position, that could be a key reason why, and if so the price will be paid by Syrians and Lebanese more than anyone.

The al-Assad regime’s most important foreign backer in terms of actual military resources wasn’t Iran but Russia, so I will be very interested to see whether Russia is able to negotiate to keep its bases under the new Syrian government. That government shouldn’t want to pick a fight with Russia, after all; doing so would only make it harder for it to consolidate its power. And while Russia spent significant resources propping up the Syrian government during the civil war, Russia—unlike Iran or Turkey—doesn’t have any reason to care about the nature of the Syrian regime; its relationship is entirely transactional. So if they are able to retain their bases, will Russia be more inclined in the future to hedge its bets with respect to allied regimes? Or, since unlike China the main thing Russia has to offer its clients is military assistance, will it be constrained to stand by its clients even to the point where they grow brittle and incapable of defending themselves? It’s a question with broad implications for Africa, where Russia is an increasingly prominent supporter of repressive regimes.

All of the foregoing, of course, presumes that the new Syrian government itself is primarily interested in consolidating its power rather than pursuing ideological projects in ways that could undermine it. I was completely blindsided by their success, so I’m not going to pretend I know anything about Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. But I still say that the key question about them is precisely that one: whether they are primarily interested in consolidating power. If they are, then whatever the complexion of the regime that emerges, its moves should at least be readily comprehensible. If not, then a descent into chaos becomes much more likely—and in that context, any sort of accommodation between the outside powers that have meddled in Syria for so long becomes hard to imagine.

And what about the United States? President Biden attempted to take credit for the fall of the al-Assad regime, arguing that American support had bogged down Russia in Ukraine and had helped Israel weaken Hezbollah and Iran, all of which left al-Assad bereft of the sponsorship it needed to survive a determined assault. Bret Stephens, in a similar vein, suggests that Syrian’s should thank Israel for their liberation. (It’s a suggestion that will likely sound strange to Syrian ears at a time when Israeli troops have crossed into Syrian territory and Israeli bombers are striking Syrian military assets that would otherwise fall into the hands of the new regime, but be that as it may.)

Yet, while it’s unquestionably true that loss of patronage cost Bashar al-Assad his throne, it was the backing of those patrons that empowered him to foolishly rebuff all attempts to negotiate an end to the civil war, which is what created the conditions for that war to resume. Conversely, the failure of the fractious Syrian opposition with its range of ideologically-motivated backers to unseat al-Assad in the 2010s, the decision by President Obama not to escalate American involvement in Syria’s civil war, and the trauma of the horrifically brutal Islamic State, together provide the context for the emergence of HTS as a more unified force. Whatever it does become, if Syria doesn’t devolve into the next Libya, I suspect that the experience of that crucible will be one key reason why.

All of which suggests that the United States would benefit greatly from drawing the opposite conclusion from the one we usually draw, that our action or inaction was decisive in shaping events. Events are chaotic, and while any number of ideological factions are eager to change the world, we would do better, first, to understand it.

The problem with Biden trying to take credit for any allegedly good thing that happens under his government is that he never even so much as mentions that he's trying to do any of these good things before they happen.

In the long run, the benefit to Turkey will hurt Israel more than the blow to Iran will help Israel, but because we are incapable of thinking outside of the most tired binaries nobody will report it that way. Either way, the options are indeed another Libya or in every way that matters an ISIS that's internationally recognized as a legitimate government.