Reparations and the Black Nationalist Counterfactual

Imagining that debate throws useful light on the very different debate we are having

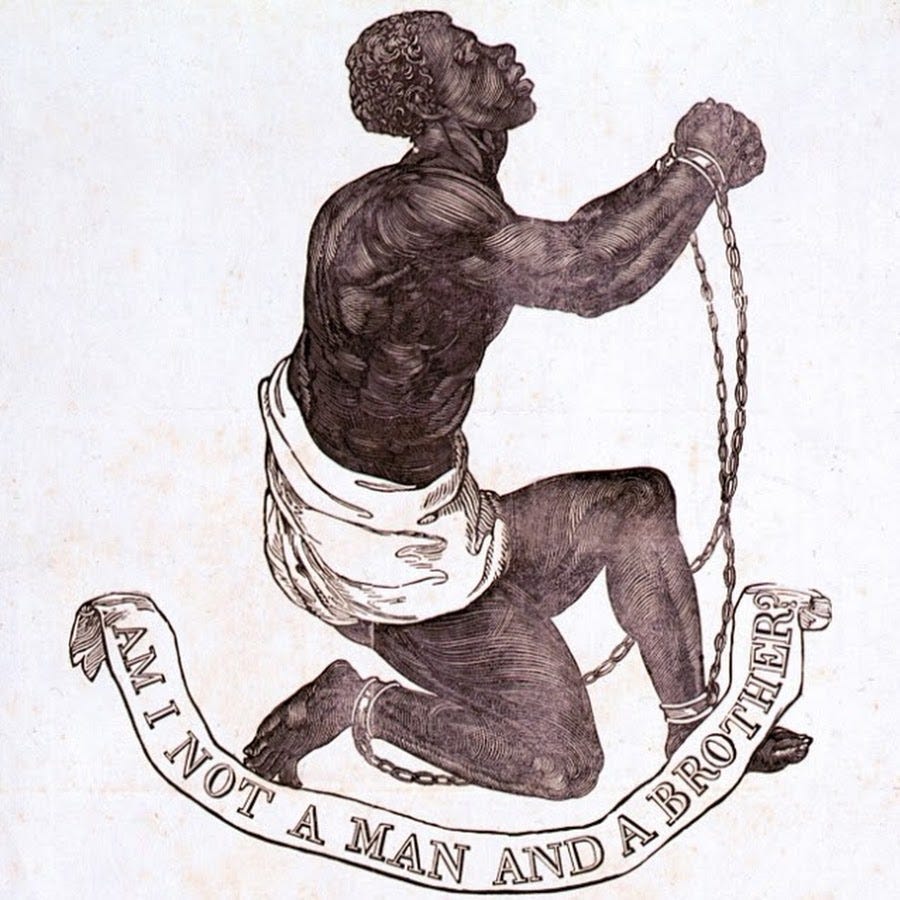

The Official Medallion of the British Anti-Slavery Society

Indulge me in a historic counterfactual. At the outset of the Civil War, President Lincoln did not intend to end slavery, much less to enfranchise former slaves with full American citizenship. On the contrary: his explicit aim was to restore the Union on the basis that existed before the Dred Scott decision and the Fugitive Slave Act, setting the country on a gradual path toward abolition. The bulk of the slaves, he assumed, would be resettled somewhere outside the bounds of the United States.

So imagine if, over the course of the Civil War, instead of embracing abolition and enfranchisement of the former slaves, the North had turned instead to abolition combined with nationalism. Freed slaves would not be promised a share in the commonwealth but a commonwealth of their own — 40 acres and a mule in an independent country carved out of, say, the southern half of the state of Florida.

I, for one, am very glad that American history did not take that turn. The contributions of Black citizens to our national culture and history have been immense, and imagining their absence is painful. But more importantly, my counterfactual would have meant a re-founding of America on an even more tragic basis than what actually happened with the abandonment of Reconstruction. In a very real sense, it would have meant making America an explicitly White nation, a key part of what the Confederacy was fighting for. Nonetheless, in part because I was raised in a Zionist household and can imagine how I might have felt as a Jew in 19th-century Russia, I can readily imagine how, if I were a Black American, I might feel the opposite way from how I do, and see even an ugly founding such as I hypothesize as a tantalizing nationalist might-have-been.

But that’s not why I brought the counterfactual up. I brought it up in the context of the debate about reparations for slavery and structural racism. I’ve written about the idea of reparations before, in response to Ta-Nehisi Coates’s original article in The Atlantic, and returned to the subject in 2019 as a panelist in a discussion hosted by BRIC, a wonderful Brooklyn arts and culture organization. With H.R. 40 advancing further than it ever has legislatively (though still very far from passage), and winning rhetorical support from the White House, I thought it was an opportune time to revisit the subject, with a particular view to how that debate might have played out in that counterfactual world versus how it plays out in our own.

Before I get into that, though, I want to review what I see as some basic principles that I think are often obscured, to some degree I think deliberately, in discussion of the subject.

First of all, like a case of tort liability, reparations involves assessing a harm, finding of fault, making restitution, and thereby achieving closure. What “closure” means is that at the end of the process, the particular harm in question can no longer be the basis of a claim — the entity responsible for the harm no longer owes a debt to those harmed because of the harm. (This is a point I will return to later on, because there may be other debts owed that are not rooted in harm or fault.) Closure isn’t absolute — a claim can be reopened if it’s clear that liability or fault wasn’t adequately assessed — but closure is definitely the objective.

But unlike a torts case, reparations is inherently inter-communal. If I have personally suffered at the hands of the state or some private entity, I can sue. If I am not alone, but rather part of a large group of people who have suffered similarly, we can join our cases together through a class-action suit. If we win a monetary award at court or through an out-of-court settlement, I don’t think it would be correct to say that those constitute reparations, even if there is an admission of fault, because our class does not constitute a distinct community that bears a collective grievance, even if we all happen to live in the same community or share certain characteristics. (I don’t want this to be a semantic debate, so if “reparations” comes to be or already is frequently used in tort cases, then I’ll just say that it’s a distinctly different meaning of the term.) What needs to be repaired, via reparations, is the relationship between communities, or between a community and the state, because such a rupture requiring repair is a political problem and not just a matter of dispensing justice towards an individual. Another way of putting it: miscarriage of justice in an individual case does not undermine the state’s authority (though habitual miscarriage of justice would eventually do so), but miscarriage of justice towards a distinct community certainly could.

Related to the above, the true purpose of reparations is to transform inter-communal relations and set them on a new and more positive foundation. These can be relations between states or between the state and a distinct community subject to its authority (or, as in the case of reparations for recognized Indian tribes, something that partakes of both). The endgame could be reconciliation or it could be separation, but it shouldn’t be mutual hostility. If it is, then the reparations must be seen as a political failure as, for example, the reparations imposed on Germany after World War I were — in contradistinction to the reparations paid by West Germany to Israel after World War II which, while highly controversial among Israeli Jews at the time, formed the basis for a more positive inter-state relationship in the decades that followed.

That’s the framework within which I understand the debate about reparations for slavery and other race-based injustices inflicted on Black Americans over our nation’s history. Talking about them in terms of reparations means talking in terms of past harms and fault, and the purpose of assessing them and making restitution for them is to achieve closure on that aspect of the country’s past, and establish race relations in America on a different and more positive footing.

Is that likely to be the result? I’m really not sure. In the past, I’ve been skeptical, for a variety of reasons. I’ve worried, for example, that you’d have to define and limit the community of claimants, which could be highly divisive within the Black community. (This is not a comparable issue for recognized Indian tribes, which keep meticulous records of who is a member in good standing and have procedures for resolving questions about same.) I’ve worried that sticker shock might prevent a settlement remotely adequate to the magnitude of the harm, which would lead to persistent pressure for renegotiation. And I’ve worried that in the lack of a clear social consensus in favor of reparations as a strategy for reconciliation, they would become a focal point for resentment, and thereby continue a familiar cycle in American race relations — but this is, perhaps, a better argument for working to build that necessary consensus over time than for pursuing a different strategy, which is precisely what advocates have been doing, with some success, as reparations has moved from being a fringe issue to being something far more mainstream.

My biggest worry, though, has always been a fundamental divergence in understanding of the nature of the closure proposed.

From the perspective of many advocates, the closure aimed at is a fundamental political transformation — in a very real sense, a re-founding of America in a manner that ends structural racism (meaning not the end of personal prejudice, which is a permanent feature of human nature, but the end of political and economic disparities that advocates argue are ultimately traceable to the long shadow of slavery and racial discrimination). The problem is that a founding is a moment in time, and this conception proposes a test that is future-looking. If those disparities don’t fade away relatively quickly after reparations, then by definition the settlement wasn’t adequate, or the harm has been compounded by new harms, and the claim remains open. In fact, there’s a very real likelihood that, even in the absence of pressure to agree to an inadequate settlement, reparations would fail to eliminate the structural disparities in American life. Thinking of reparations this way might well make closure impossible — and if closure is impossible, then reparations cannot serve their fundamental political purpose.

Meanwhile, if reparations do pass, I think there will be a powerful constituency within non-Black America that closure has been achieved by definition, and that therefore the problems of Black America are no longer something non-Black America has to think about. And here’s the thing: that this is precisely how reparations would play out naturally if they were negotiated between two separate communities that intended to remain separate. But separation is precisely the opposite of what advocates are aiming for.

That’s why I brought up my counterfactual history. My imagined state of freed slaves in southern Florida might well have had the same kinds of claims to make against the United States that Haiti has against France. Those claims might have had more or less force depending on the terms on which the Negro Republic of Florida was established, and what its relationship was to the United States over the century and and half that followed. They might have been pursued in an atmosphere of mutual amity or of mutual rancor. But regardless, there wouldn't be any expectation that closure would fundamentally transform the nature of the United States or incur an open-ended obligation toward the citizens of this hypothetical state of the descendants of freed slaves. Quite the contrary: the point of reparations would be precisely to close that obligation in a way that satisfied both sides, and everyone would understand this.

But so long as we are part of the same community, reparations cannot discharge our obligations to one another. For that reason, I think it would be very helpful for reparations advocates to separate these matters in their minds and in their speech. What reparations are intended to discharge is the debt owed due to past fault and past harm. That basis of obligation, which is one-way and not mutual, is then closed. But we still have mutual obligations to one another as fellow citizens, as members of the same political community and parts of the same nation. Differential suffering and need would therefore make just the same claim on us as citizens after reparations as they would before. That basis of obligation can never be discharged, except by the establishment of a separate sovereignty, because that basis of mutual obligation and collective responsibility isn’t about past grievances at all and does not depend on a finding of fault. It’s about the present, and the future that we want to build together.

If reparations can help re-found America on that basis, then I’m all for them. If they set that cause back, then I’m against.