Ranked Choice Voting Strikes Again

It doesn't guarantee a consensus, but it's certainly not a cheat code to put extreme or polarizing candidates over the top

In the last New York mayoral primary, ranked-choice voting was tried for the first time, and it looked for a moment like it might have a significant impact on the result. The top three contenders by that point were Eric Adams, Maya Wiley and Kathryn Garcia. Wiley was the clear choice of the progressive left, but Adams and Garcia were both moderates with differing appeals, Adams more the populist with a strong base in the Black community and what’s left of the party machine, Garcia more the technocrat without a clear base but with support spread across city workers, outer-borough homeowners, and Manhattan liberals. Each had complicated coalitions that overlapped in unpredictable ways with each other and with Wiley’s progressive coalition. That meant that the end-game might be determined by who went out first and what their voters actually prioritized—specifically, it meant that the preferences of progressive voters might determine the outcome even though their candidates were clearly a minority in the primary.

As it happened, Garcia was the second pick of enough voters who picked lesser-performing candidates—particularly Yang voters, since Yang publicly endorsed her as his second-choice pick (Garcia declined to reciprocate)—that even though she came in third in the initial round, when other candidates’ votes were allocated she rose to second among the top three. Wiley’s votes then split between Adams and Garcia, and even though Garcia won more of them than Adams did, her share wasn’t large enough to overcome his lead, and Adams won the primary. Given their coalitions, it seems likely that, had Garcia come in third, more of her votes would have gone to Adams than to Wiley, and so Adams still would have won, likely by a wider margin—but we’ll never know. More to the point, though, if Garcia had won enough Wiley voters to overcome Adams’s lead, it’s quite possible that Adams would have decried the result as unfair, since he had been the plurality winner on every prior ballot and the polling leader for the entire campaign—and since Adams could plausibly claim that in a runoff between the top-two finishers on the first ballot (Adams and Wiley), he would have won handily.

The big selling points for ranked-choice voting are somewhat contradictory with one another. On the one hand, they allow for greater choice, since long-shot candidates are no longer spoilers (as their votes are allocated in subsequent rounds to the better-performing candidates). Thus the preferences of the electorate are revealed in greater detail, which (it is argued) both makes the voters happier and provides better information to the winner about what the voters actually want. On the other hand, they assure that the winner of the election is actually a consensus candidate; if one candidate is beloved of 35% of the electorate but distrusted by the rest, but the opposition is splintered, then in a traditional election they still might win with a plurality, but under ranked-choice voting the opposition would wind up uniting on subsequent ballots. These two virtues are mildly contradictory since if we know the long-shot candidates are “really” votes for a particular better-performing candidate, then their apparent diversity isn’t adding any real information to the system—whereas if their diversity is real then the distribution of their votes is unpredictable, in which case RCV does not automatically deliver a consensus; you still may need to vote strategically to assure that your preferred more viable candidate makes it to the finals.

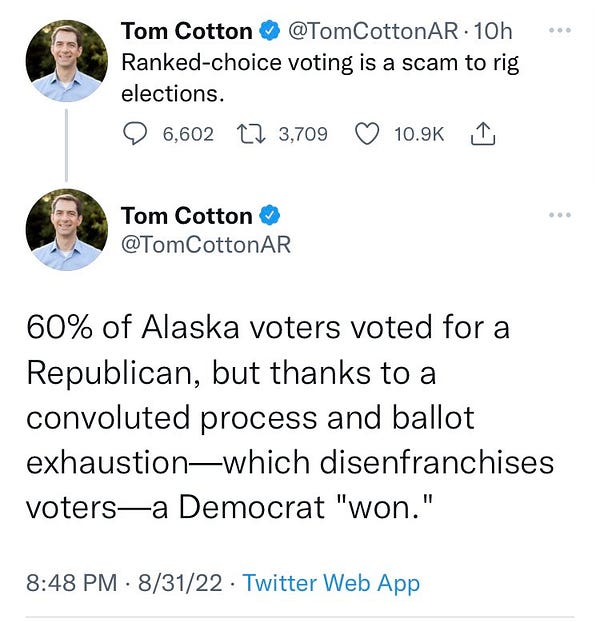

I bring all this up because of the latest ranked-choice voting surprise: the Alaska special election for the House of Representatives, which was won by Democrat Mary Peltola. Alaska is a fairly Republican state, but it has also a very independent state and has been willing to vote for Democrats in the past. Nonetheless, the result was something of a surprise, and has resulted in this kind of absurd criticism from some unprincipled Republicans:

Senator Cotton’s syllogism is as simple as it is ridiculous. As he imagines the world, voters are divided into Republicans and Democrats; Republicans always vote for Republicans and Democrats always vote for Democrats. Therefore, since candidates with an “R” by their name won the majority of votes in the Alaska special election, a Republican should have won. The whole point of ranked-choice voting, though, is that it reveals the true preferences of voters—and lo and behold, it turns out some voters are cross-pressured and some voters are in the persuadable center. It turns out that while a majority of Alaskans would vote for a Republican, they disagree about which Republican, and many of them would prefer a Democrat to Sarah Palin specifically. Given Senator Lisa Murkowski’s success (so far) in retaining her seat despite losing her primary, this should hardly be surprising.

Is it plausible that if Nick Begich had edged out Palin for second place, he would have won the election? It sure is. Similarly, it’s plausible that if independent candidate Al Gross hadn't dropped out and endorsed Peltola, she might have come in third, which might have also resulted in a Begich win. Nothing is certain of course—Peltola ran a good race emphasizing local issues and had the strong support of the Alaskan Native community, Democrats are increasingly energized in this midterm cycle despite their incumbency, and there may be Palin voters who voted only for her with no second choice, so it’s not impossible to imagine Peltola winning under other scenarios than the one that transpired. But Palin was always an incredibly risky candidate to run because of the breadth of opposition to her. Ranked-choice voting doesn’t guarantee victory for a consensus candidate, but it does make it more likely that a consensus second-choice candidate wins, and Palin was always going to have a hard time becoming the consensus second choice.

It’s important to recognize that, if there had been no ranked-choice voting, and the plurality victor had won the election, Peltola would have been the nominee. Similarly, if there had been a runoff between the top two candidates, the neutral assumption should be that Peltola would have been the nominee, since ranked-choice voting is an instant runoff. Senator Cotton isn’t complaining that the plurality winner wound up losing (as Adams might have had he lost the New York City mayoral primary); he’s complaining that someone who won a minority of votes in every round wound up losing. His “argument” is beneath contempt.

But it’s still worth paying attention to because of that contradiction at the heart of the case for ranked-choice voting. Some highly ideological voters like ranked-choice voting because it opens up space for their preferred candidates to compete and reveal the breadth of support for their ideological persuasion—and that is indeed one virtue of RCV. But it doesn’t prevent those candidates from being spoilers in the situation where they draw enough support to affect the order in which candidates drop out of the count. Fringe or extreme factions may delude themselves into thinking that by expanding the field, RCV lowers the vote threshold for getting into the “finals.” But it doesn’t lower the threshold for winning. If one party or persuasion sensibly unifies behind a single candidate plausibly capable of becoming the consensus choice, the other party or persuasion needs to do the same or they risk blowing a winnable election by losing persuadable cross-pressured and moderate voters.

Which, come to think of it, is kind of how it works in a traditional partisan contest. Funny, that.

Australia has been using preferential voting (i.e. ranked choice voting) for decades. It tends to moderate politics. It also means voters don’t have to um and err over whether to vote for who they want or against who they really don’t. Australia is generally very policy successful, so there’s that. We also have compulsory voting which also tends to moderate politics, as there is no mileage in driving people away from the polls.

https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/BriefingBook46p/LastRecession

Sorry, Noah - missed this one.

It's obviously possible to take the same set of ballot papers (same set of preferences) as in NY or the AK-AL special and apply any of the many Condorcet methods, rather than RC-IRV. Notwithstanding King Cotton's nonsense, it seems likely to me that a Condorcet method would have given Begich the win. No idea about the NY mayoral primary. (n.b. I certainly prefer RC-IRV to FPTP, but exactly for reasons like the AK-AL special, I'd prefer any of the nearly interchangeable Condorcet methods).

OTOH, given a populace which cannot apparently even grasp RC-IRV (certainly the voters in Maine seem to have no trouble understanding RC-IRV), Condorcet is a Bridge Too Far, I get it.