One Way To Prevent an Auto-Coup: Make Dictatorship Legal

Justice Alito's Norm Macdonald logic

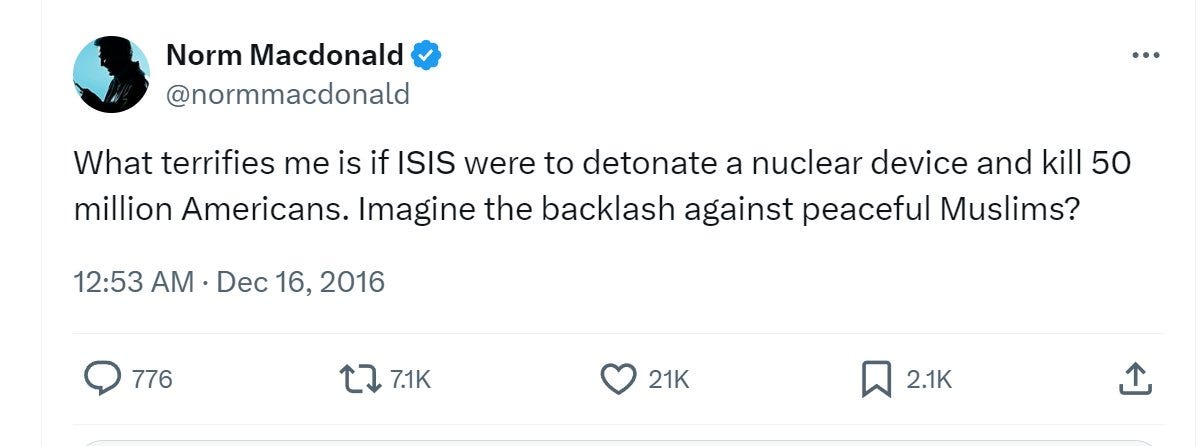

I’ve been trying to wrap my brain around the Norm Macdonald-style logic of Justice Samuel Alito’s conjecture that, when faced with a president who tried to hold onto his office illegally, perhaps the thing to do is grant him absolute immunity so that future presidents won’t try something similar in order to avoid prosecution.

But, in the interests of civil discourse, I’ll take his conjecture seriously. Let’s go step by step. First, did this hypothetical president actually commit crimes, or did the president not commit crimes? And if he did, were those crimes conducted in pursuit of his proper duties as president, or were they conducted in contravention of those duties? Three possibilities: crimes were not committed; crimes were committed, but they were committed in pursuit of his proper duties; and crimes were committed, and they were committed in contravention of the president’s proper duties.

In the first case, the scenario is one where the hypothetical president believes (rightly or wrongly) that, upon losing the election, he will be prosecuted by the opposition for crimes that he never committed, or, possibly, crimes that were never committed by anyone—that the opposition will, in other words, frame him. That sounds like a bad thing we’d want to prevent. But is saying “a president cannot be prosecuted for acts committed while president” a necessary and sufficient way to prevent this eventuality?

I don’t see how. We’re positing an opposition that is sufficiently unscrupulous that they will frame an opponent for crimes they didn’t commit in order to imprison them. Why would such an unscrupulous opposition by daunted by the Supreme Court saying that this particular avenue for vengeance was cut off? So it isn’t sufficient. Moreover, it isn’t necessary because, unless the courts themselves have been corrupted, we should be able to rely on them to impartially try the former president and exonerate him since he did not commit any crimes. The proposed remedy only makes sense if you imagine simultaneously that the courts cannot be trusted to try the president fairly and that the unscrupulous opposition can be trusted to shrug their shoulders and give up at the idea of vengeance if those same courts tell them the president is immune.

Now let’s take the last case: the president did commit crimes, and they were not crimes committed in pursuit of his proper duties, but rather crimes that were corruptions of the office: embezzling government funds, for example, or attempting to falsify an election. If a president committed such crimes, and they came to light, he’d have every reason to fear prosecution. He might indeed wish he could prevent such a prosecution—so is it inconceivable that he would try to remain in office unlawfully so as to prevent those crimes from being prosecuted? If so, is absolute immunity from prosecution a necessary and sufficient mechanism for preventing him from taking that terrible step?

Again, I don’t see how. First of all, if he did commit venal crimes, then it seems to me the question isn’t “will he refuse to leave office for fear of prosecution” but “why did he think he would get away with those crimes, and how can we make sure that future presidents don’t presume that they could get away with committing crimes?” Granting absolute immunity from prosecution would obviously do precisely the opposite: it would tell future presidents that they should expect to be able to get away with committing such crimes, and encourage them to commit them. Second, how, in this hypothetical where a president did not have a grant of immunity, would refusing to leave office help shield him from prosecution? Such an act, after all, would be a blatant violation of the law—for which he could be prosecuted after the police came to forcibly remove him from the office he refused to cede. Criminals routinely commit further crimes to cover up their initial criminal act, but the point of the cover up is to prevent people from finding out that they’ve committed a crime. Dictators certainly have more powers to cover up corruption than rulers subject to democratic accountability, but declaring oneself dictator isn’t exactly a subtle move unlikely to attract notice. Finally, if Alito’s concern is to discourage a president from making such a declaration, how exactly would blanket immunity from prosecution—which would effectively cede such dictatorial powers to the president—be a solution? The whole thing just boggles the mind in its transparent absurdity.

That leaves the middle case: a president who committed crimes not for corrupt ends but in pursuit of his proper duties. An example would be a president who, in violation of federal and international law, ordered the torture of captives in order to extract information deemed vital to an ongoing war effort. Is this a case that warrants a blanket immunity from prosecution?

This is probably the kind of case that is on Alito’s mind, and it does deserve some attention, both because the letter of the law is not always clear and, more importantly, because I think we all understand that there are some kinds of emergencies that justify setting aside the law, and the presidency is the office most likely to be vested by events with the responsibility for deciding whether a given emergency qualifies, and deciding what to do if it does. That decision ought to be a fraught one, though, and part of it being fraught is knowing that, if a president makes the wrong call, he may very well be prosecuted for his actions after leaving office. Remove that caution, and we’ve essentially eliminated any legal restraint on presidential power. Meanwhile, if we’re positing that the hypothetical president was acting patriotically in taking those actions, I think we can rely on that same sense of patriotism to inhibit him from declaring himself dictator simply to avoid prosecution.

As it happens, we have recent examples globally of all of the above possibilities. It’s worth looking at them to consider how a blanket immunity from prosecution would or would not have shaped history differently.

The president of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (known universally as Lula) was indicted for corruption after leaving office as part of a broad investigation that turned up numerous malefactors, was convicted, and was sent to prison. But both the conviction and a judge’s further bar against Lula from running for office were subsequently overturned on the grounds that the judge was biased and the prosecution corrupt, and Lula ultimately returned to office. His opponent, the incumbent Jair Bolsonaro, initially seemed poised to refuse to cede that office, but quickly folded and accepted the election result when it was clear the armed forces would not support an auto-coup. I’ve written about Lula’s case before so as to throw light on the potential political consequences of prosecuting Trump. But in our timeline, the system worked: the legal system dealt with the legal issues, the political system dealt with the political issues, and the military stayed loyal to the political system and the constitution rather than the would-be dictator. Meanwhile, in Alito’s alternative timeline where Lula was constitutionally immune from prosecution, Operation Car Wash might well have never have gotten off the ground in the first place, and the rampant corruption that did obtain in his administration would have continued unabated. Would that have been an improvement over the history that Brazilians lived through? More pointedly, might not the army have sided with Bolsonaro if they understood themselves to be the only force capable of preventing a corrupt leader from returning to power, since legal remedies were unavailable?

A second case: Benjamin Netanyahu, the current prime minister of Israel, has been under indictment for corruption for years, and has comprehensively warped Israeli politics around his determination to avoid being tried and potentially convicted. This extended to forming the most extreme right-wing government in Israel’s history and proposing a major overhaul of Israel’s government structure that would substantially subordinate the judiciary to the government, a move that prompted massive nationwide protests for months—the largest in that nation’s history. But notwithstanding his determination, when Netanyahu lost the previous election—after several previous elections that ended in deadlock—he left office, as he was obliged to do. The scenario that Alito is worried about—a criminal executive refusing to cede power—did not happen, because the executive understood that the political system would not tolerate it. Now, would Israeli history be better if Netanyahu had been formally immune from prosecution from the beginning? The main difference would be that, in the absence of a legal remedy for corruption, his opponents would have to turn to a political remedy—ousting him from office and keeping him out—which is a goal they had to pursue anyway to achieve a prosecution.

Finally, consider the case of president George W. Bush of the United States, who as president authorized a program of torture of certain individuals captured during the Global War on Terror that was (notwithstanding the memos his lawyers penned at the time) pretty clearly illegal—but that was also clearly undertaken in a sincere attempt to protect national security. Bush was never prosecuted for this illegal activity; indeed, nobody of consequence was prosecuted for it, in part because his successor affirmatively decided that the right thing to do was “move on.” Was Bush concerned that he might be prosecuted after leaving office for authorizing violations of the law? I remember reading pieces fretting that the International Criminal Court might take action, but I can’t remember anyone seriously suggesting that Bush would be prosecuted by the American legal system. The reason, obviously, is that there was a widespread recognition that his actions were, whether right or wrong (I think they were wrong) undertaken in the earnest belief that they were necessary to fulfill his duties as president, and the political system—both parties—closed ranks around him and his entire administration on that basis.

How would this history have been different if Bush had been immune from prosecution? At first glance, it wouldn’t have been different at all. But it might have been different if Bush had known that his illegal actions were not widely regarded as sincerely undertaken to fulfill his duties, and were wildly unpopular to boot. In those circumstances, Bush might have hesitated before taking an action he believed to be necessary, because he would have reasonably feared it would cost him the election, and that he would then be prosecuted after leaving office. And, of course, the president might be right and the people wrong, and by not taking the necessary action he might bring on disaster.

If we dig into Alito’s hypothetical, then, the real scenario he’s trying to prevent is not an auto-coup by a president fearful of either wrongful or rightful prosecution. It’s a scenario where a president is inhibited from doing something illegal that he believes to be necessary, because he fears that the political system will not close ranks behind him as it did behind Bush. That could happen, most likely because the thing he thinks is necessary is a terrible idea, in which case it should be prevented, but also possibly because he is wiser than the people, or that the people are so divided in their allegiance by party that they are incapable of closing ranks behind any leader. In the latter cases, though, the complaint is not that democracy requires such immunity, but that democracy itself is the problem, and what we need to do is empower the president to be the true sovereign.

I’m not deluded about the defects of democracy, both in theory and in American practice. But I’m going to defend it in Winston Churchill’s terms nonetheless: it remains the worst form of government—except for all the others.

The conclusion of your penultimate paragraph, Noah--"the complaint [of the conservative majority on the Supreme Court] is not that democracy requires such immunity, but that democracy itself is the problem, and what we need to do is empower the president to be the true sovereign"--leads directly into your comment to Damon which he quotes in his latest substack post: "[C]ourts are extremely valuable umpires in a normal political context. They could even potentially mediate between mutually-hostile organs of government—between Congress and the presidency, between the states and the federal government—and thereby defuse constitutional crises. But if the rest of the political system turns to them to prevent a dictatorship, they’ll be sorely disappointed." I couldn't agree more...except that, critic that I am of our Court's I-think-much-too-expansive claims in regards to their own role in making constitutionalism operable, I can't help but wonder: to what degree has our contented acceptance of the "valuable empires" model of the Court (John Roberts! Balls and strikes! Non-partisan!) actually made the positions of Alito, et al, assume must be considered that much more likely? Significantly, I would say.