No Alternative

The rise of the German far right and the exclusion vs. normalization dilemma

It’s been a while since I did a pure electoral politics post, so today we’re going to talk about the rise of the far right in Germany.

Two years ago, I wrote a column about how Europe is trending further and further right. Since then, against my expectations, Britain’s Tory government has become deeply unpopular, and in Spain the far-right Vox party whiffed in the latest election. But apart from that, the trends I identified have continued. Italy is now governed by a coalition led by a party with Fascist roots; Sweden is governed by a center-right coalition with support from the far-right Sweden Democrats; Marine Le Pen’s National Rally cracked 40% in the 2022 runoff, currently outpolls Emmanuel Macron’s party in polls for the next parliamentary election, and outpolled Macron himself in a presidential poll held earlier this year.

And then there’s Germany:

In the latest YouGov poll, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has risen to 23%, which puts them closer to the leading Christian Democratic parties (CDU/CSU, at 27%) than to the third-place Social Democrats (SPD, at 17%) who lead the current government. This is the best poll for the AfD, but it’s not an outlier; an average of recent polls has the AfD at 21% and they’ve been rising steadily all year. Unsurprisingly, because this is Germany we’re talking about, the rise of the far right has caused more than a little consternation, both in Germany itself and across Europe.

The AfD is benefitting from general discontent with the current coalition government, but also, I suspect, is being rewarded for some of its substantive positions, especially on migration and environmental legislation, and possibly for its stance on Ukraine which is far more conciliatory toward Russia. Even if these views do not garner anywhere close to majority support in Germany, the AfD is well-positioned to consolidate a large minority position that sees itself as unrepresented by the other major parties. Given the fragmented state of German politics this may well be enough to vault the AfD to major party status.

Does this mean we’re about to see Germany—of all countries—welcome a far-right party into government?

Not necessarily. We’re still more than two years out from the next scheduled federal election, and the AfD could easily fall back into the pack before then. It’s happened to rising German parties before. From 2006 through 2011, the Greens rose steadily in the polls, until they surpassed the SPD; then they fell back dramatically over the next two years and performed unimpressively in the 2013 election, finishing fourth just behind the far-left Linke. After the election they rose again, and for brief moments in 2019 and 2021 the Greens were all the way at the top of the polls, well above the SPD and just barely above the CDU/CSU. But once again they declined before the 2021 election, ultimately finishing a distant third and becoming a junior partner along with the Free Democrats (FDP) in the current coalition led by the SPD. The AfD itself has experienced notable but temporary peaks before: in 2016 when they briefly polled as the third largest party, and in 2018 when they were briefly in a three way tie for second place. Both times they fell back significantly before the election. So something similar could easily happen again, for any number of reasons.

But the opposite is also possible. Notwithstanding their setbacks, the trajectory of the Greens over time has been from the periphery of politics into the center. That’s come with some moderation of their views, but also with some transformation of the center to accommodate their views (on environmentalism for example or on migration) as legitimate despite being relatively extreme. Could the same thing happen with the AfD? I don’t see how anyone could call it impossible. More to the point, though, unless their core issues are co-opted by a more established party, or the driving forces of German politics change radically, I wouldn’t expect the AfD to simply fade away, even if they don’t keep rising. And if those issues remain at a boil, and the AfD remains their primary champion, they could keep rising. The question then becomes how long the party can be contained and, if it cannot be any longer, how it can be accommodated.

To date, the overwhelming strategy of the German political system has been containment—or, rather, exclusion. The AfD has been locked out of power everywhere except in the odd municipal election. That record is about to be tested at the state level. Saxony, Brandenburg and Thuringia are all part of the AfD’s heartland in the former East Germany. State parliamentary elections are scheduled for 2024 in each of these states, and the AfD is currently polling near or above 30% in state polls in all of them. If those polls hold up, it is possible that the AfD will enter or even lead one or more state governments in the east. (In a recent poll in Thuringia, all possible coalitions were opposed by the voters by at least 2-to-1, but an AfD-CDU coalition was the least-hated option, supported by 31% and opposed by 63%.)

If that happens, it would be a political earthquake. But it’s not the first earthquake we’re likely to see involving the AfD. The AfD is sometimes discounted as a purely regional party of the former East Germany. But in Hesse, where state parliament elections will be held in October of this year, the AfD has recently surged in the polls to nearly 20%. If they don’t fall back before election day, the AfD could earn the second-largest number of seats in that state—which is not part of the former East Germany. The AfD are very unlikely to enter the government there under any circumstances, but depending on just how well they do and how the rest of the vote divides, keeping them out of government might require a coalition of all the other major parties to form a government. That would leave the AfD as the official opposition—which itself would be an earthquake, one that could reverberate elsewhere beyond the old East Germany.

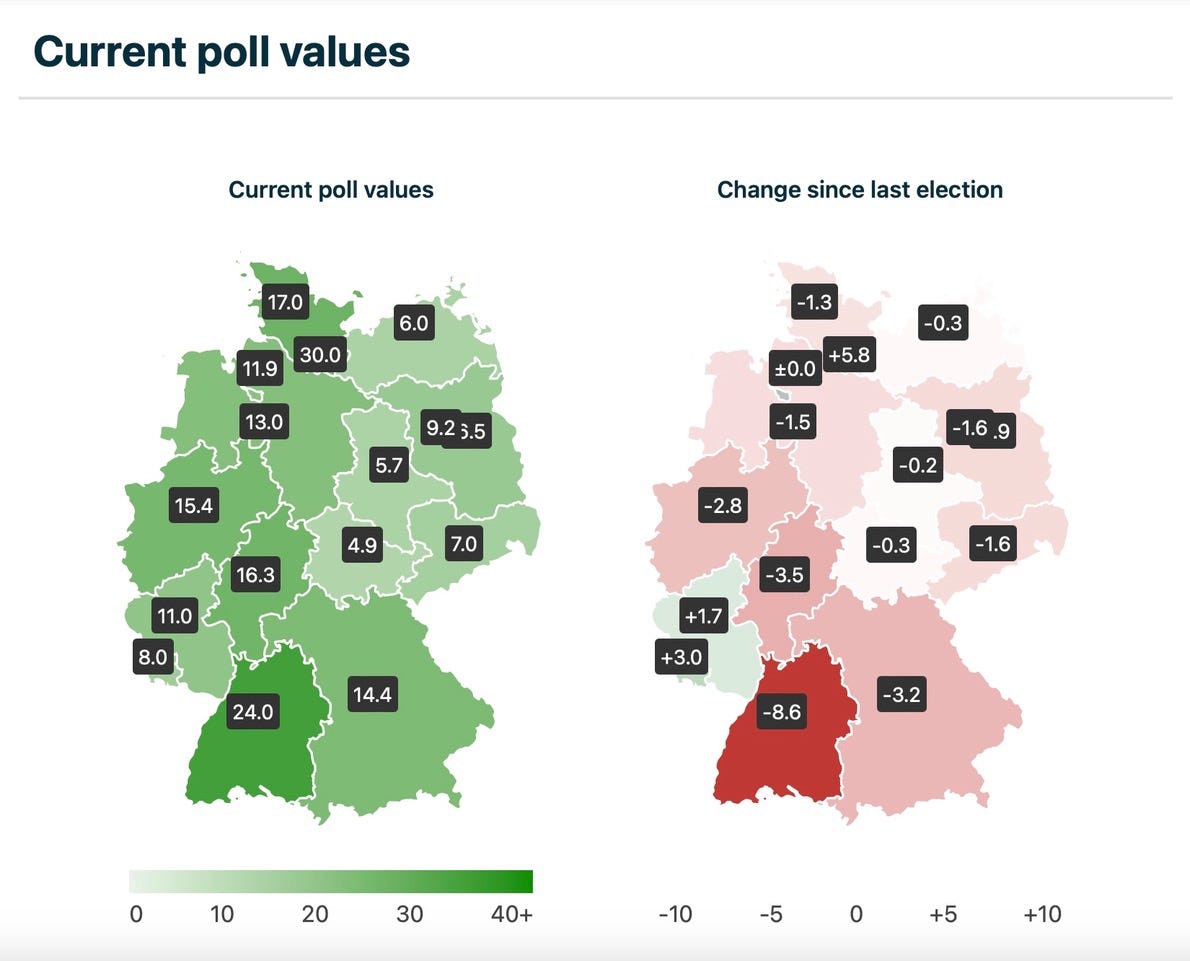

While they are far from power in most of the west, the AfD is currently polling in the double digits everywhere but Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg and Bremen. Here’s a map of the AfD’s support and their gains since the last state elections across Germany:

That looks to me more like a party with a strong regional base than a party with an exclusively regional appeal. Compare it, for example, to the support for the Greens:

The two maps are not quite mirror images, but there’s clear regional variation in both. Yet nobody would discount the Greens as a purely regional party. So why see the AfD that way?

It’s quite plausible that the AfD is approaching a peak and is about to fall back, either to its regional base in the east or to an even lower level of support. But I don’t think we can discount the opposite possibility, that the AfD might do surprisingly well in this year’s and next year’s regional elections, ride that performance to a strong showing the next German federal elections, and win support not only in the former East Germany where it will do best but in parts of the West as well. If that happens, then keeping the AfD out of power indefinitely, even at the federal level, is probably impossible.

A quick look at how current polling would translate into seats and possible coalitions illustrates just how difficult a strategy of exclusion might become.

If the election results were to look like the latest YouGov poll, the current “Traffic Light” coalition (Red-Yellow-Green = SPD+FDP+Greens) would be irrecoverably trounced. That grouping would only represent 36% of the vote and have 270 seats—well short of a majority. Swapping in Linke instead of the FDP to make a purely left-wing coalition would only gain them 10 seats more—still well shy of a majority. Even if, in some imaginary world, the FDP and Linke could be induced to sit together in coalition (extremely unlikely given their diametrically opposed views on the economic matters that are core to both parties’ identities), they’d still be well short of a majority. No left-wing coalition could be formed if the election result matched those polls.

What coalition could replace them though?

A “Grand" coalition (CDU/CSU+SPD) such as governed Germany from 2005 to 2009, and again from 2013 through 2021, wouldn’t work. That grouping would represent 44% of the vote and have 342 seats—12 shy of a 354-seat majority. The fact that the two historically dominant parties of post-war German history are now polling at less than a majority together is something worth taking a moment to contemplate. For comparison’s sake, the “Grand” coalition represented 69.4% of the vote after the 2005 election, 67.2% of the vote after the 2013 elections and 53.4% after the 2017 elections. Frankly, they’ll have to come up with another name for it after such an election result; a coalition can’t be very grand if it doesn’t even collect a majority of seats.

You could, of course, expand the “Grand” coalition by adding the FDP to make a “Germany” coalition (Black-Red-Yellow = CDU/CSU+SPD+FDP). Such a coalition would be able to form a government based on the above poll—but only barely. It would represent 49% of the vote and have 380 seats. Forming such a coalition would be very dangerous for the SPD however. The free-market-oriented FDP is significantly to the SPD’s right on economic matters, so on their core issues the SPD would clearly be the junior partner in a generally right-wing coalition. If their voters got almost nothing of what they want from coalition agreements, the SPD would risk seeing them defect to the Greens, to the AfD, or to Linke, at the next election. Coming on the heels of the acute disappointment with the SPD’s performance in power right now, such defections could send the party the way of France’s once-formidable and now nearly-defunct Socialists. Meanwhile, there’s also a very real risk that the FDP falls so low that it drops below the 5% threshold for seats, as they did in 2013. If that happens, of course, the redistribution of those seats among the parties that do clear the threshold might make the “Grand” coalition viable after all—but if so, it would be a very narrow thing indeed.

The other way to expand the “Grand” coalition would be by adding the Greens, making a “Kenya” coalition (Black-Red-Green = CDU/CSU+SPD+Greens). Such a coalition would have a more substantial majority; they’d represent 58% of the vote and have 447 seats. Moreover, it would be well-balanced between left and right, so coalition agreements would look like a true compromise. For that reason, I can more easily imagine the formation of such a coalition than a more narrow “German” coalition. Such a coalition is precisely what might govern the state of Hesse after this year if the AfD comes in second in their state parliamentary elections. The problem, though, is that a “Kenya” coalition would represent the entire broad political center even more thoroughly than a “Grand" coalition would. There would be no major mainstream party in opposition; the only major party left out would be the AfD. Under those circumstances, the AfD would become the official opposition and be poised to benefit from any discontent with the governing coalition—discontent which would be pretty inevitable when that coalition is so broad that its every action is a compromise. If the goal is to stop the AfD from becoming the largest party, this probably isn’t the way to do it.

There is one remaining possible coalition that would exclude the AfD but not leave it as the sole major party in opposition. That would be to swap out the SPD from the current coalition and replace it with the CDU/CSU. The resulting “Jamaica” coalition (Black-Green-Yellow = CDU/CSU+Greens+FDP) could form a government—but just barely. They’d represent 46% of the vote and have 358 seats. That’s a razor thin majority, and the vast ideological gulf between the coalition members would make it inherently unstable. Angela Merkel tried to form just such a coalition in 2017, and couldn’t pull it off. The dramatic rise of the AfD might concentrate everyone’s minds to get it done—but it might also pull the CDU/CSU further away from the Greens ideologically in an effort to co-opt some of the AfD’s positions, which would make a “Jamaica” coalition even harder to assemble.

Which leaves the to-date unthinkable: accommodation.

Based on that YouGov poll above, a simple Blue-Black coalition (CDU/CSU+AfD) would represent 50% of the vote and would have 387 seats—more than a “Traffic Light” or “Grand” or “Germany” or “Jamaica” coalition. Adding the FDP to make a “Bahamas” coalition (Black-Blue-Yellow) would bring the total to 425 seats—nearly as many as the “Kenya” coalition, but with a far more coherent ideological orientation representing all stripes of the German right. Though led by the mainstream conservative Christian party, the historic party of government, it would otherwise resemble the coalition currently governing Italy.

The main problem with forming such a coalition (politically, I mean, not morally) is that CDU/CSU voters and FDP voters have long expressed an aversion to any coalition with AfD. But that may be changing. In a July poll, about half of CDU/CSU voters continued to say that a coalition with the AfD should not be considered under any circumstances—but about 44% were open to the idea. Among FDP voters, the numbers were 45% absolutely opposed, 48% open to discussion. If there were lots of other viable coalitions, those numbers would probably keep the AfD out of the halls of government. But if the election results looked like the YouGov poll, then the realistic choice is between admitting the AfD into government, or forming a wall-to-wall coalition of the mainstream to keep them out, which would elevate them to the official opposition. If that’s the choice, I’m really doubtful the cordon sanitaire will hold.

This has been the challenge for every country faced with the challenge of right-wing populism in our era. Do the mainstream conservative parties welcome the populists as partners, trying to keep them as junior partners and thereby influence them toward the mainstream? Or do they try to co-opt the populist party’s program and thereby neuter them as a political threat? Or do they form coalitions with other mainstream parties to keep them out of power? None of these strategies has a consistent and reliable track record of working, but for my money the riskiest strategy is the last one, because once the right-wing populist party has been elevated to the status of the official opposition, the odds are high that they will eventually not only be in a government but will lead it. That’s the situation in France today.

But if accommodation becomes the goal, then the question is the terms. And here the AfD poses distinct difficulties of its own. Numerous right-wing populist movements claim to have moderated over time—Rassemblement National does; Fratelli d'Italia does as well. These claims can be (and are) disputed, but the mere fact that they are made is evidence of a desire to integrate into and cooperate with the mainstream. And a number of right-wing populist parties in Europe have in fact moderated on at least some dimensions, becoming more Atlanticist and/or more Europeanist over time rather than exclusively nationalist in their orientation. The AfD, though, has gone the other way. They started as an Atlanticist party but since the Ukraine war began have taken a strong line against German involvement and have evinced suspicion of American intentions and are outspoken in their opposition to sanctions on Russia. They started as a moderately Eurosceptic party but have become more explicitly anti-Brussels over time. They’ve moved to the right on immigration as well (which is where the populist right generally is) and on other social issues, but most notably in a German context where environmentalism has its own major party, they have embraced outright climate denialism. Most of these views put the AfD deeply at odds with any potential coalition partners.

And then of course there’s the question of Germany’s relationship with its own history. The AfD rejects the postwar (really post-1968) German reckoning with the Nazi past, and calls for a resurgence of national pride in terms that are not merely civic but in terms of a Germanness that is cultural and even racial. This isn’t really a policy matter, but it’s a profoundly important question in Germany that would be exceptionally difficult to accommodate without what amounts to a cultural (counter) revolution, one that anyone who remembers German history should shudder to contemplate.

Hence the dilemma. From a moral perspective, there really are some lines that ought never be crossed—but the practicalities of coalition-building don’t really care about moral lines. The larger the AfD gets while running against the German political consensus, the harder it will be to accommodate it and the harder it will be to exclude it. The AfD is not yet presenting German politics with the dilemma I’m describing. But if it stays on its current trajectory, it will.