I don’t know who Dmitri Alperovitch is, and I have no way of independently verifying some of the factual claims in the thread below. But from where I sit, he makes a persuasive case that Russia really is preparing to invade Ukraine. It’s about forty tweets, so it’ll take a while, but I strongly encourage you to read the whole thing.

If Alperovitch is right, and war is imminent, then the short-term practical question is whether we can do anything to prevent it. Trying to deter an attack by threatening to respond militarily strikes me as incredibly foolhardy. After Georgia in 2008, and after President Biden already declared military options off the table, Russia would have every reason to treat any such threat as a bluff, and call it. Then we’d have to either make our threat good, getting into a shooting war with a major nuclear power, or we’d have to fold, in which case the credibility of NATO would be shot, with far worse consequences for the security of Europe. Eliminating those unpalatable alternatives, as the Biden administration effectively already has, leaves preemptive appeasement: making Russia an offer so generous it makes military action unnecessary. I can’t imagine us doing that either. Which means that our policy will be largely reactive, and if war comes, the United States will oppose it with measures unlikely to reverse its outcome.

But the larger question is more interesting to me, namely: was there any way of preventing Russian revanchism in the first place? I think in retrospect there might have been, but it’s not hard to understand why the West failed to take that path.

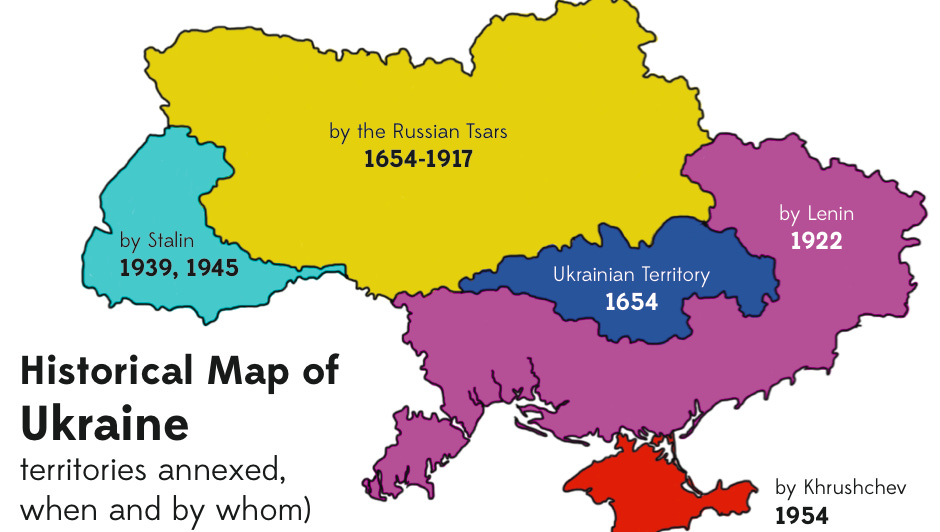

The road not taken would have required renegotiation of the borders of the new states created in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Those borders were internal ones established by the Soviet Union for its own purposes, and did not necessarily have a long history nor line up with boundaries as determined by language or ethnicity. With respect to Ukraine specifically, a chunk of pre-World War II Poland that lay over the Curzon Line was annexed to the Ukrainian SSR by Stalin, and Crimea was gifted to the Ukrainian SSR from the Russian SFSR by Khrushchev. There were also a great many self-identified Russians living in former Soviet republics—naturally enough, given that they had been part of the same country only recently—with a particularly high concentration in the Donbass region of eastern Ukraine which abuts Russia.

If one were drawing borders from scratch, then, with a view to preventing future conflict, it’s unlikely one would do so along the precise lines that demarcated the various Soviet republics. Renegotiating borders, though, opens a very nasty can of worms, where national sentiment can quickly drive both sides to demand more than they can plausibly get. Velvet divorces, like that between Czechia and Slovakia, are rare. This is a very familiar post-colonial problem. So when the Soviet Union broke apart in 1991, the simplest way to establish new international borders was to say they would be the same as the old internal ones, and to hope that, with time and peaceful coexistence, the border itself would come to matter less and less to either side.

This settlement, though, failed in practice almost immediately. In the early 1990s in Transnistria, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, breakaway former Soviet republics faced pro-Russian secessionist rebellions from within their own previously-autonomous regions, and Russia, then much weaker than it is now, intervened immediately to support (and, indeed, to foment) these movements. At the time, I fully expected something similar to happen in the Donbass region and in Crimea, and I worried about northeastern Estonia as well. Ukraine in particular seemed likely to devolve into civil war between a pro-western West and a pro-Russian East sooner or later. But at the time, Russia was far too weak to force a resolution in their favor anywhere.

The mid-1990s, then, was the moment of opportunity, if one ever existed. The West was at the height of its prestige, and Russian President Boris Yeltsin’s luster had not yet entirely worn off within his country. The collapse of Yugoslavia had revealed the dangerous potentialities in these apparently-frozen conflicts. Rather than assume that Russia would “outgrow” nationalism, the United States and its NATO allies could have mediated a generous settlement that restored to Russia some of what it had lost territorially (Crimea, in particular), in exchange for ending Russian involvement in separatist movements beyond their borders (which might well have required repatriation of some Russian populations). The West could also have drawn a line between the former Soviet Union and the former Warsaw Pact (with the Baltic states treated as an exceptional case), and tacitly recognized special Russian interests in the former by renouncing any effort to incorporate them into any security-oriented treaty body that did not also include Russia. We could, in other words, have behaved as though Russia were still a Great Power, albeit a diminished one, and as though we had no interest in seeing it diminished further, as indeed we rationally did not. And we could have hoped, thereby, to earn Russia’s acceptance of America as a relatively honest broker between powers rather than its resentment of America as a contemptuous former adversary always determined to press its advantage.

I don’t know if that would have worked, honestly. It’s possible that Putin would still have risen as Yeltsin’s successor, and would have repudiated any agreements that Yeltsin might have made. It’s quite likely that states like Ukraine would have truculently refused to make any deal of that kind; indeed, they would rightfully have viewed such moves as selling out their independence and abandoning them to their former colonial overlords. As I said earlier, there are good prudential reasons not to try to solve problems before they become acute; sometimes you wind up only making the problem worse. But even if the opportunity really was there, it’s hard to imagine America being sufficiently far-sighted to recognize it, as indeed we did not. It’s easy to blame President Bill Clinton for the callowness of American foreign policy at the time, but the fact is that many of his administration’s opponents, who came to power in the George W. Bush administration, wanted America to be even more unilateralist and less considerate of our rivals’ interests in setting the terms of the new world order. Geopolitics was a game, and we had all the strongest pieces on the board.

That’s all water under the bridge now, though. If Russia invades Ukraine, seizes the Zaporizhzhia, Kherson and Kharkiv oblasts (or whatever slice of territory Putin turns out to want), and either annexes them to Russia or molds them together with Luhansk and Donetsk into a nominally-independent Russian-aligned state, the last nail will have been driven into the coffin of that order, inaugurated by the first Gulf War. There will be no fig leaf of ambiguity to hide behind. A Great Power, unhappy with losses imposed upon it in a period of weakness, and feeling its resurgent strength, will have reversed those losses by forcibly altering the borders of its neighbor. That’s a precedent that will reverberate around the world.

I suspect the main way it will reverberate is by fostering a renewed commitment to independent deterrence on the part of smaller, threatened states. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Ukrainian government briefly inherited the Soviet-era nuclear weapons that were stationed on their territory. Quite sensibly, they surrendered these rather than alarm both the United States and Russia with their intentions. With the 2014 Donbass war, though, some Ukrainians began to voice regret for that decision, however unavoidable it was.

But for another small, relatively prosperous state facing a larger, revisionist neighbor, the case for acquiring nuclear weapons has rarely looked better.