Is Populism Possible Without Demagoguery?

If not, then what's a high-minded person who finds the populist critique convincing to do?

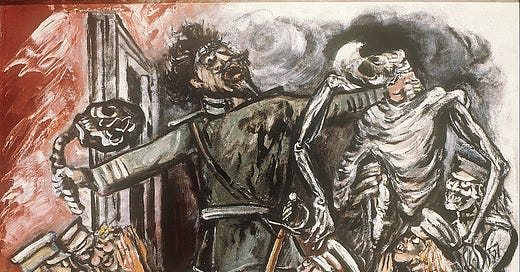

The Demagogue by José Clemente Orozco

I was very curious to read Ross Douthat’s recent interview with Senator J.D. Vance, and my reaction was very similar to those of Andrew Sullivan and Damon Linker. (As an aside, Linker has been on a tear lately; if you aren’t already a subscriber of his, you really ought to be.) That is to say: I thought Vance made a reasonable (if obviously highly disputable) case for why he might have embraced the various aspects of Trumpism: the producerist and nationalist economic philosophy, the realist anti-moralism in foreign policy, the profound distrust of corporate, political and media elites, even the determination to undermine political independence in the administrative state. But his “reckoning” with Trump’s personal character and the impact that had both on his presidency and, especially, his conduct after losing the 2020 election is just flatly dishonest. And that dishonesty really does make it hard for someone like me to take the rest of his argument seriously.

But I’m not the one Vance is trying to reach, am I? And as I thought about his decision—so emblematic of his dispensation—to drink the Kool-aid with gusto, I wondered whether the “Trumpism without Trump” that sometimes-sympathetic commentators like Douthat have pined for periodically isn’t a mirage, not simply because of the overwhelming fact of Trump himself, but because of something deeper about the nature of populism.

Where, after all, have we seen a successful populist movement that isn’t invested in a charismatic leader who systematically undermines the normative checks and balances of liberal democracy? One that doesn’t wind up riddled with corruption for some combination of personal venality and as a mechanism for controlling underlings? Whether we’re talking about India’s Narendra Modi on the right or Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador on the left, we see similar phenomena, similar concerns. Part of that is surely that corrupt demagogues naturally turn to populism as their best route to power. But maybe it’s not just that. Maybe it’s also because you can’t successfully do populism without demagoguery and corruption.

Why should that be? Well, populism’s essential critique is that forms that appear to be neutral and constitutional have in fact been captured by a class of self-serving elites who are alienated from and oppressing “the people” who, by rights, are the source of authority for these elites. That’s the essential critique whether the target is central bankers or tech company CEOs, the military brass or the judiciary, and whether that critique comes from the left or the right. If that critique has force, then it’s reasonable to argue that you can’t fix the problem without breaking those supposedly neutral and constitutional forms, which, in turn, would require you to wield authority that comes from an extra-normative place, from some combination of personal charisma and the ability to rouse “the people” to direct action. Moreover, if you want to convince “the people” that you are the kind of person who will actually follow through if granted that authority, you have to not only make an enemy of those institutions that you claim have been captured by corrupt elites, but be the kind of person who cannot very plausibly ever find refuge among those elites.

Consider the predicament of Claudia Sheinbaum, the newly-elected president of Mexico. Though she was AMLO’s chosen successor and by all reports is a true-believing member of his party, by temperament and training, she’s a technocrat. That has led some to hope that she will moderate her populist predecessor’s tendency to identify the state with himself and backslide on Mexico’s forty year transition away from one party rule and toward a more liberal, democratic order. But observers are also aware that those precise aspects of AMLO’s presidency, which are intimately bound up with his personality, were important reasons both for his broad popularity and for his ability to successfully accommodate elite interests behind the scenes. Sheinbaum’s success depends in part on her ability to achieve the same political results without a similar personality. Asking her to achieve that while also moving substantively in a liberal direction seems a bit much to ask. If anything, I suspect she’ll have to do the opposite, to establish her populist bona fides through some kind of action that cuts hard against her technocratic liberal image.

Meanwhile, without a strong political base of her own she’ll have a harder time reining in cronyism, but will run considerably more risk than someone like AMLO would if she does not do so. If Sheinbaum doesn’t have an image of Brazil’s first female president, Dilma Rousseff, in some private location to serve as a warning, she should. But the point is: these are the risks of being a leader of populist movement who isn’t a natural leader of such a movement, which is to say: not a demagogue.

What I’m suggesting is that it’s not just that a character like Trump could only get traction by running as a populist wrecking ball aimed at the system. It’s that a truly populist movement, one that takes its own critique seriously, can’t really do without a character like Trump, with all his profound defects of character that threaten liberty, order and good government. If that’s the case, then maybe it isn’t so surprising that someone like Vance, if he became authentically convinced of the validity of the right-populist critique that Trump championed, would become naturally radicalized to insouciance about or even admiration of Trump’s most appalling qualities and actions. He’s surely too smart not to realize that his justifications are nonsense. But he might also be smart enough to intuit that the movement and the man cannot be separated not only in practice but in principle.

I don’t want to overstate the case; Trump is sui generis in many ways, not least in his violent response to losing an election, something we haven’t (yet) seen from the most comparable figures abroad. And I don’t want to give Vance too much credit either; the line between personal ambition and the advancement of principle is hard for politicians to discern at the best of times. Nonetheless: even if an American populist revolt didn’t need Trump specifically—even if it would have been better off with someone like (say) Robert F. Kennedy Jr. at the helm—it needs someone who is similarly capable of serving as a wrecking ball and incapable of being assimilated into the Borg. And someone like that is inevitably going to be genuinely threatening not only to the targets you, the high-minded populist sympathizer, think are deserving of the wrecking ball treatment, but those that do not deserve the wrecking ball—indeed, even those that you know deep in your heart are the structural pillars that keep our political edifice from collapsing entirely.

Much of this critique seems to turn on the definition of "populist", a notoriously squirrely term. Was FDR a "populist"? I think you could make a very good case that he was: He styled himself as a champion of the little guy, he upended norms about the scope of government power, he even threatened to "pack" the Supreme Court to get it to rule his way. But his presidency is widely regarded as extremely successful, at least by the center and the left, and I don't think many would say that it was shot through with "demagoguery and corruption" in the way you claim any populist government *must* be.

If we used the term “popular activism” instead of “populism” would we be too quick to denigrate it? Would we be too quick to worry about demagogue? Does the ever likely possibility of demagogues mean that every form popular activism or democracy is doomed?

Eugene V Debs (a socialist and labor union leader) typifies as an anti-demagogue when he told his followers, “No. I cannot lead you into the Promised Land. And I wouldn’t do it even if I could, because if I could lead you into the Promised Land, what would stop some other leader from turning you around and leading you out again? (I paraphrased this.) He, of course, meant that leaders and followers must work together to build a more perfect and less unjust society

I have trouble with the terminology used in the tile “Is Populism Possible without Democracy?” I think we should be talking about “authoritarian populism” or perhaps NOT even shying away with terms like quasi-fascism or proto-fascism. In earlier times what we are worried about was called “Bonapartism or Caesarism. But when popular excitement about an unfair system is being manipulated by certain elites to attack other elites and to scapegoat certain sectors of the population, we are really talking about modern day fascism.

When thinking about WHY we are asking if populism is possible without democracy, we should ALSO think about why we are NOT asking if democracy is possible without populism (as popular activism)! We should also remember (without succumbing to crazy conspiracy thinking or scapegoating the rich) that dangerous threats to democracy do NOT come only from popular failings and excitements.

To me “populism” is democracy — or rather that aspect of a “democratic rule of law” where the focus is only on “the rule of the people” without ENOUGH consideration of other important aspects of the “rule of law” side of the equation such as precedents (for stability), due process, (for stability and protection of individuals and minorities) along with equality of all before the law and (it deserves reemphasis ) protections of minority rights (which is also necessary for stability and a broad sense of legitimacy or “buy in”. Or, to put it another way, populism is that aspect of democracy that focuses only on the “rule of the people” without taking into consideration that democracy is also a “process”. But most importantly, “populism” may have too limited a view on what constitutes “the people.”

If you want to say that All democracy (or all “populism”) requires a demagogue then wouldn’t you have to say that FDR was a demagogue? Alastair Cooke (reporting back to England about the US in the 30s) pointed out that criticizing FDR in the wrong saloon could get somebody’s face punched in. That may make you want to say that “populism” is the “thuggish” side of democracy. But I just prefer to think of it as the aspect of democratic (popular) enthusiasm that lacks good leadership or self governing habits-of-mind necessary for rule of law and stability. Leaders who exploit this aspect of democracy (or democratic enthusiasm OR HUMAN NATURE) are the true enemies of democracy, the general good, the rule of law, and even of ‘the people’.

The original “Populist Movement” (or “People’s Party) in the US began in Texas among farmers and spread across the agrarian West while also making strong inroads and alliances with urban labor unions. You can see its legacy in all kinds of Cooperatives (including Cooperative Banks) some of which were not just inspired by the history but are institutional legacies from the late 19th century. The original Peoples Party made serious efforts to even organize across racial lines, but racism, antisemitism, and nativism were strong cultural currents that elites used to divide, discredit, and disorganize the Populists while more “respectable” and educated middle class types in the GOP co-opted most (but not all) of their causes as “Progressives” who get the credit for a large number of reforms that were also supported by Populists.

So if populism isn’t democracy, it is a crucial element of democracy. To equate populism with trumpism or fascism is to equate fascism and trumpism with democracy.

Populism is PEOPLE. Democracy is PEOPLE. WE the PEOPLE are not always wise, not always well informed, and not always good. We are all subject to grievances and resentments. We all have a difficult time understanding our complex politics and economics — and trying to figure out who or what is responsible for injustices in our society when they persist and when they grow. It is in our nature to define ourselves as a “people” in an exclusionary, aggressive, or hostile manner when we feel deprived and threatened. When we feel deprived or threatened, we ALL have more tendency to look for scapegoats and conspiracies. Demagogues are politicians and government leaders who exploit this tendency to excess in ways that appear unseemly. But it’s rare to have an effective demagogue who doesn’t have a lot of support and sympathy from other government leaders and members of ‘the opulent classes” (a term used by James Madison).

Populism has a long history of rallying around good leaders. FDR was one. Eugene V Debbs was another. So was William Jennings Bryan. None of them was perfect, but in terms of respecting democratic processes, they all (mostly) qualify as “good.”

Note that for democracy to survive, there must be rule of law. But also for “rule of law” to endure there must be democracy. And for both to reinforce each other in a positive and humane way, there must always be pressure for a broad definition of ‘the people” that is not exclusionary or oppressive. This kind of pressure which also tries to expand our definition of “person” and “citizen” (meaning a person with rights to participate in a democracy) is always opposed by our own tendency to exclude. And it is this anti-humane, anti-democratic tendency which can lead any of us to disparage democracy by calling it “populist” (as a slur) or by using terms like “woke” in a derogatory way to disparage the tendency to extend personhood to the excluded or oppressed.

If anything, the current trends that led to trumpism are not so much the result of TOO MUCH popular enthusiasm for organizing, politicking, and engaging with democracy, but a result of the TURNING AWAY from popular activism once the Vietnam War ended and popular victories were won under both Democratic and Republic administrations (but with strong Democratic majorities in Congress) during the 60s and 70s including Civil rights advances, rights of women (who were not truly full citizens until the 1970s), Medicare, Medicaid, Rights for the Disabled, etc. Let’s face it, certain business groups (mostly associated with the GOP) have been running down government and politics (read democracy and popular activism) since at least the 1920s. Those enemies of popular activism had major set backs under FDR in the 30s and from popular activism in the 60s and 70s. By the 1980s though, the enemies of popular activism succeeded in instilling anti government and anti political sentiments into the popular mind.

If we don’t like certain forms of popular activism, we shouldn’t denigrate all forms of it, we should look for examples of the kinds of popular activism that keeps democracy vital.

Democracy is a process and a struggle. It cannot only be learned about in school, or by talking, reading, and writing. It must also be learned through action and activism where mistakes will be made, but hopefully with the kind of leadership (or governance) that helps us learn from our mistakes. The ideal would be when that kind of governance is “self governance” that is widespread though the population where more and more individuals understand that “freedom” = “SELF control” not so that we are atomized, isolated, alienated and therefore vulnerable. But so that we can responsibly participate in many forms of self correction activism within the checks and balances of a rule of law democracy which is hopefully always developing to be more just, more humane, more compassionate, more inclusive, and more responsive to everyone’s needs and talents.