Pennsylvania Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman, listening; photo by Governor Tom Wolfe

Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman’s decisive victory in the Pennsylvania Senate race is being spun by some as a victory for the progressive, Bernie Sanders wing of the Democratic Party, and by others as a sign of a shift towards a new center that could recapture the working class voters who swung from Obama to Trump. My old colleague Damon Linker, meanwhile, saw the Pennsylvania primary as more about style than substance. Fetterman and his strongest opponent, Representative Conor Lamb, agreed on paper on nearly all issues, but Lamb “looks and sounds like he's playing a bit part on The West Wing” while Fetterman looks like a Joe Rogan fan.

Who’s right? Fetterman himself says he’s “just a Democrat,” noting that while Sanders’s 2016 run (which he supported) aimed to shift the party to the left, the party has moved to the left, such that he’s now fairly clearly in the mainstream. But style does matter. It doesn’t trump substance, but it’s sometimes what enables people to hear, and trust, the substance even when it isn’t different from what other candidates would have said.

Consider, for example, the politics of trade. Both parties have shifted notably against free trade since 2016, and the political center of gravity now favors continuing to unwind our economic integration with China and developing an industrial policy capable of besting Chinese competition, restoring high-wage domestic manufacturing, and protecting against supply disruptions. An across-the-board anti-free-trade agenda is probably a bad way to achieve the latter three goals; strong trading relationships with Europe, Latin America and Southeast Asia will make it more possible for us to rebuild high-value manufacturing and especially to make our supply chains less brittle, both of which are vital to meeting the Chinese challenge. But that’s not the important question politically. From a political perspective, the important question is who credibly sounds like they care about those goals. Fetterman’s schtick, inasmuch as it seems authentic (which it seems it does) probably makes him more credible than a generic moderate. He could use that credibility to promote bad policies or good policies, but the fact of that credibility helps him given where the political center of gravity is.

Fetterman is not a moderate on cultural issues any more than he is on economic issues; he’s an across-the-board progressive. His schtick might still help, however, with voters who aren’t primarily motivated by cultural issues, and who may disagree with him in a low-intensity way, if he comes off as someone who can listen to and accept disagreement. I don’t think that matters much on an issue like abortion (Fetterman has said a top priority of his will be codifying Roe v. Wade), where high-intensity voters own the issue. It might matter on immigration; Fetterman is passionately pro-immigration, in part for very personal reasons (his wife was an undocumented immigrant), and I suspect he’s well to the left of Pennsylvania’s center of gravity on the issue. But his affect might still help him if people who think he’s too left wing on the issue, but don’t care that strongly about it, believe that his views are genuine and not the result of political pressure from activist groups. It will almost certainly matter on crime. I expect Fetterman to continue to advocate for alternatives to incarceration while also making noises about investing in law enforcement that many other Democrats are making, and I suspect his affect will help people hear the second part of that message in a way that they might not hear it from a generic Democrat.

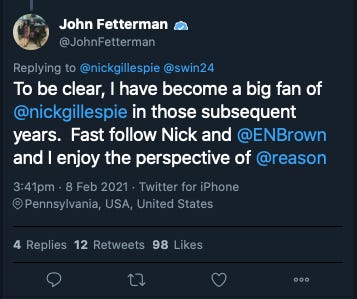

His best move, though, would be to disavow framing cultural issues as a “war” altogether. Fetterman is an unabashed cultural progressive, and doesn’t hide it. But you can be an unabashed cultural progressive while still respecting the rights of people whose views you disagree with. You can be someone who argues with barstool conservatives—even yells at them—as opposed to someone who tries to get them thrown out of the bar. Fetterman can say that free speech is good, for example, in a way that sounds forthright and not mealy-mouthed. This kind of signaling has almost no real policy content, but it can still matter in terms of increasing the receptivity of people who find the typical Democratic discourse irritating:

All of that describes Fetterman’s potential. His most significant vulnerability, I suspect, is that his economic ideas are very 2016. We’re in a highly inflationary environment now, which means that things like raising the minimum wage, universal health care, etc. are all pushing the wrong way macroeconomically-speaking, driving inflation up and prompting the Fed to raise rates further. Inflation is a very high-salience topic, and I think Fetterman could get into real trouble there—particularly if his Republican opponent can focus credibly on the subject. Fetterman can’t plausibly claim his preferred economic policies will reduce inflation, and he can’t plausibly moderate those policies since they are the core of his identity (the shift wouldn’t be credible with the center and would also lose him support on the left). Any Democrat would probably have trouble on this topic, but Lamb would probably have had less trouble than Fetterman precisely because his preexisting branding as a wonky moderate would have let him credibly shift to a more hawkish stance on budgetary matters.

The one good card Fetterman’s does have in his hand on this subject is that he’s pro-fracking and more generally in favor of balancing decarbonization with protecting fossil fuel jobs. This is another stance that lines up with his bro gear style, so he’s likely to be credible on it. Fetterman could plausibly take a “all of the above” stance on energy that could appeal to people worried about high gas prices, which is the most-salient aspect of inflation for most consumers.

By far the most important thing Fetterman has going for him, though, is that he won his primary without much institutional support. He has the chance, therefore, to be perceived as his own man. I’ve been arguing for years now that the biggest problem Democrats have in the post-Obama period is that they haven’t had an actual leader, someone the rank-and-file are ready to take cues from. Fetterman doesn’t want or need to be Joe Manchin, someone whose credibility at home depends on loudly breaking with the party on certain key votes (fewer of them, though, than his left-wing critics realize). But he does need to sustain and reinforce that impression that he thinks for himself, and votes accordingly.

As the saying goes, the key to success in politics is authenticity. Once you can fake that, you’ve got it made.