Fun With Proportional Representation: German Edition

Could the BSW and Linke bring the AfD to power?

Europe’s leaders are still reeling from the speech by Vice President Vance in which he called for an end to the ostracism of parties of the extreme right. As someone who has argued before (most recently here) that such ostracism is no longer practically viable, I think the Vice President is basically right on that point, though he seems enthusiastic about what I find ominous.

But it’s far from clear that his effective endorsement will actually benefit the AfD in the upcoming German elections. It’s certainly possible that undecided voters will see Vance’s intervention as permission to vote with their gut, but it strikes me as at least as possible that the opposite will be the case and that wavering voters will get their backs up about American leaders telling them how to vote, and turn against the AfD out of spite. (Something purely reactive seems to be moving Canadian voters in that fashion right now.) Most likely of all we’ll never know because other events will muddy whatever effect Vance’s speech may have had between now and the election next week.

Absent a major shift in the polls, though, the contours of the likely result are fairly clear. The center-right CDU/CSU will come in first, followed by the far-right AfD, followed by the center-left SPD and the Greens. No party will be able to form a majority, and so the question will be whether the CDU/CSU form a coalition with the SPD, or with the Greens, or whether they break their solemn vow and link hands with the AfD.

Here’s the interesting thing though. The most important factor determining whether either of the centrist coalitions are viable may not have anything to do with precisely how many votes those parties get or precisely how well the AfD does. Rather, the most important factor may be how three minor parties hovering near the 5% threshold for inclusion perform.

In system of proportional representation, which Germany follows in a modified form, parties earn representation based on the proportion of the vote that they receive. Only parties that earn more than a minimum threshold percentage of the vote, however, get any representation at all; if they fall below the threshold, the unallocated seats associated with their percentage are divided proportionally among the parties that did clear the threshold. Because of this, when the threshold is a meaningfully large percentage, and several parties are on the edge of crossing that threshold, the number of seats won by the major parties can be materially affected by the number of minor parties that successfully cross the threshold.

That is the case in Germany today. Three parties—the business-oriented FDP, the far-left Linke, and the left-populist BSW—are all hovering just above or just below the 5% threshold for inclusion in the Bundestag. The FDP, weakest of the three in current polling, was the traditional coalition partner for the CDU/CSU for many years, and would be again if they manage to squeak across the threshold. But their presence could complicate coalition negotiations with other parties since they would strongly object to a coalition with the AfD and differences between them and the SPD and Greens were what shattered the current “traffic light” coalition. The BSW and Linke are each more likely to cross the threshold than the FDP is—the BSW spent much of the campaign polling well above, and Linke has surged recently. But both are completely unacceptable coalition partners for the center-right CDU/CSU, so any seats they win would come out of the hides of parties that could be viable partners.

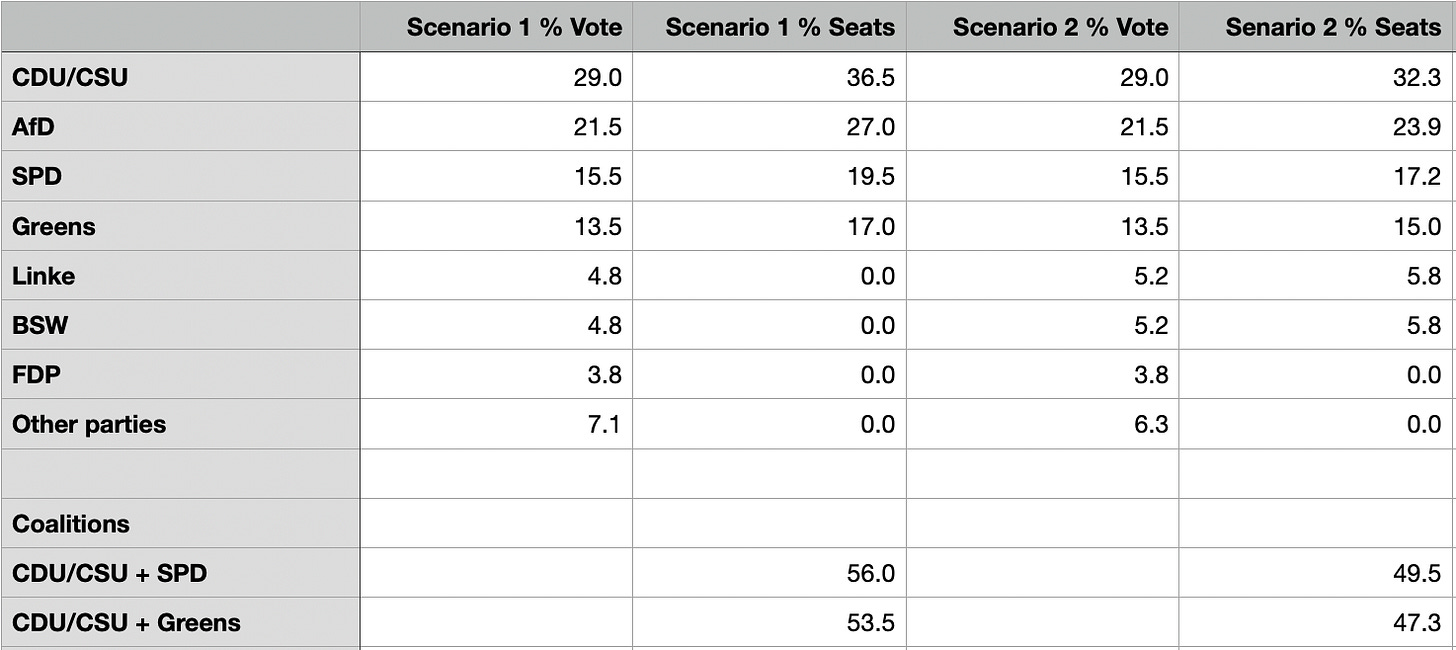

How much of an effect could this have? I did a little noodling to find out. Here were my results:

The percentage of the vote I’ve used for the major parties in both scenarios is in line with their current polling. For the minor parties, in the first scenario I assumed that Linke and the BSW fell just below the threshold and received no seats, while in the second scenario I assumed they each earned just enough of the vote to get seats, with the difference coming from the very small parties who have no chance of representation (and who in the last election collectively won well above the percentage assumed in either of the above scenarios). In both scenarios, I assumed the FDP failed to clear the threshold.

I want to be clear: these scenarios are extremely quick and dirty estimates. Germany actually allocates some seats in the Bundestag by constituency, so it’s very likely that a geographically concentrated party like Linke would earn seats even if they failed to clear the 5% threshold. But though oversimplified, I think the analysis above still points to something important: small changes in the votes for these minor parties who will definitely not be part of the next governing coalition could nonetheless determine what the governing coalition does look like. Specifically, if neither the BSW nor Linke clears the threshold, then two possible centrist coalitions—Red-Black and Red-Green—are each likely viable based on current polls. If they both clear the threshold, however, then based on current polls neither two-party centrist coalition is likely to be viable, and the only viable non-AfD coalition will therefore be a “Kenya” coalition—Red-Green-Black—comprising the entirety of the political mainstream.

Does that matter? It might. If the only viable non-AfD coalition involves both the SPD and the Greens, the the CDU/CSU can’t play one off the other in negotiations; Red and Green can present a united front of the center-left, and together they will have roughly equal weight to the CDU/CSU. That could pull the coalition negotiations leftward—but that in turn could mean that the CDU/CSU gives more serious consideration to breaking their repeated promise and forming a coalition with the AfD. Meanwhile, if a Kenya coalition does materialize, the CDU/CSU’s voters will probably not be happy with how left-wing the coalition’s terms turn out to be. The AfD, standing alone in opposition and alone as the “true conservative” voice in the next Bundestag in this scenario, should therefore have much to capitalize on for the next election.

In other words, a vote for either the BSW or Linke—both parties of the far left—could conceivably push the next government to the left even if it reduces the number of seats that the left-wing parties in the coalition receive, but could also benefit the AfD even if it reduces the number of seats that the AfD (and the CDU/CSU) receive. It’s extremely hard to game out the strategic consequences of a vote for the these parties, other than that if they clear the threshold it will make life harder for the next coalition leader, the CDU/CSU. Yet, it strikes me as entirely plausible that parties of the extreme left could make some hay out of annoyance at Vance, perhaps enough to vault one of both of them over the 5% threshold.

Every electoral system has such vagaries, some scenarios where small differences could lead to wildly different political outcomes. In America, we think of the virtually tied 2000 Presidential election that was settled by the Supreme Court, or the 2016 Presidential election where Donald Trump clearly won the Electoral College while decisively losing the popular vote, as evidence of unique disfunction, but if the far left squeaks in to the Bundestag, Germany could well wind up being governed by a coalition of the center-right and far-right with a solid majority of seats backed by only a plurality of votes. How different is that?

Or consider the last Israeli election, which brought to power the farthest-right government in Israeli history, one that may have determined that country’s future for a generation or more. That government won a solid majority of 64 seats (out of 120) on the back of a bit over 48% of the vote. How could that be, given proportional representation? Because two parties—the left-wing Zionist Meretz and the Arab party Balad—fell just short of the threshold for representation. Had Meretz joined with Labor (has they have since, forming the Democrats), and Balad joined with Hadash-Ta’al (as they had during the era of the Arab Joint List), and retained their vote shares, the current coalition would likely not have won a majority of seats, and would have been unable to form a government. Who knows how different history would have been in consequence?

Every electoral system is a balancing act, and every electoral system has edge cases where weird things can happen. When there is no broad political consensus, the balancing act gets harder, and the weird cases get more common. We’ll see how close to the edge Germany gets on Sunday.