On September 11th, 2001, as I was walking uptown to my boss’s apartment with colleagues from the firm I then worked at (a financial derivatives shop in midtown Manhattan), I remember hearing some of the traders talking about how stupid al Qaeda was. Now that we’d been hit, America was going to retaliate, and they had no idea what they were in for. You don’t get it, I said. Of course they know we’ll retaliate. They must expect that, must have a plan for what they’ll do then. Nobody would pull a stunt like this without a plan to win.

It turns out, though, that al Qaeda had no real plan at all. They vaguely expected that America would be terrified by the attack, that the faithful would rally around their banner in the wake of their victory, and that thereby they would topple the Saudi monarchy, reclaim the holy places, and drive the infidels from the Arabian peninsula. America did itself and the world enormous damage through our response to the 9-11 attacks, but that damage was not part of al Qaeda’s “plan” because there was no plan.

Does that mean al Qaeda’s actions were irrational? Not necessarily. They were based substantially on ignorance, yes, but poor understanding is not the same as irrationality. But apart from their ignorance, the leadership of al Qaeda did appear to understand something fundamental about their relative position in the scheme of world power. They were very, very far from the power they wanted, and had no realistic prospects for building steadily toward their goal. In finance terms, they held a basket of options that were very far out of the money. If that’s what your portfolio looks like, it is rational to pursue strategies to dramatically increase the volatility of the assets underlying your options even if those strategies have a negative expected value, because incremental increases in those assets’ value won’t be enough. Your only hope of winding up in the money is if something changes radically, and fast.

I’ve been thinking about that apropos of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In a certain sense, it looks completely irrational. Ukraine is not simply going to give up—if they were ready to do that, they could have done so before the invasion and spared themselves a great deal of death and destruction. Holding Ukraine by force will tie down Russia’s army for an extended period, weakening its ability to project force elsewhere. Diplomatically and economically, Russia will be more isolated than ever. What possible gain could be worth the cost, and the risk, of an outright invasion?

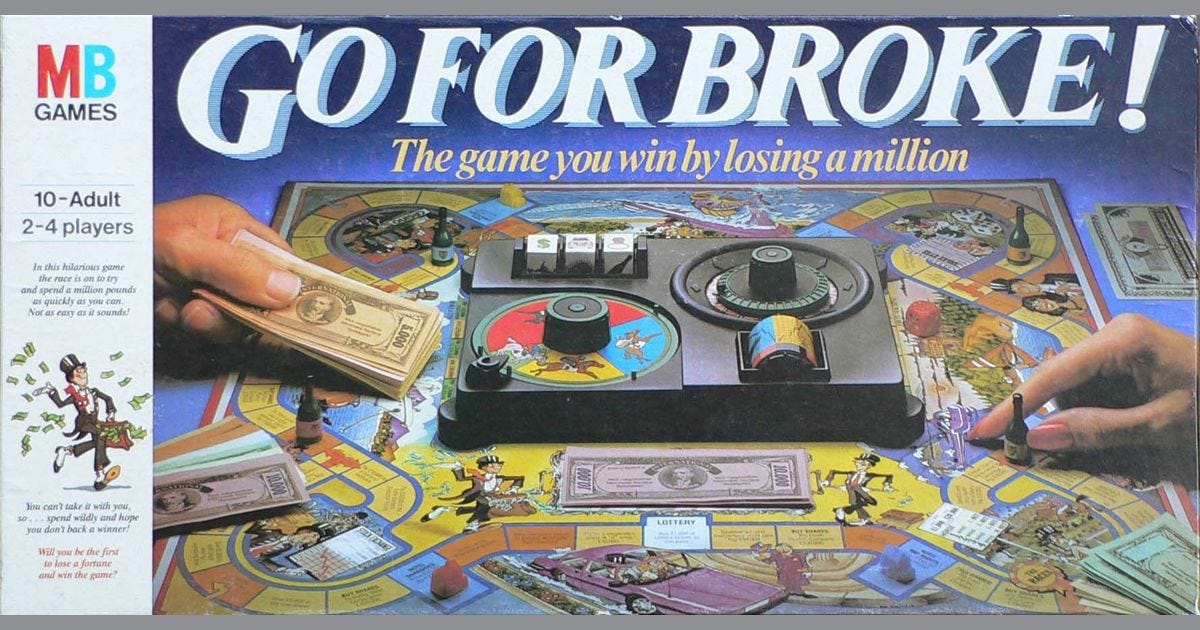

Perhaps, as with al Qaeda, it’s simply that Putin’s basket of options was sufficiently far out of the money that it made sense to go for broke.

Of course, al Qaeda was a terrorist group while Russia is a major power with a lot more to lose. But major powers have made similar kinds of rash decisions, particularly when they believe they are backed into a corner. Imperial Japan, for example, launched its attack on Pearl Harbor in part because they misunderstood how America was likely to react, and in part because they underestimated America’s industrial potential. Even so, they can’t have missed the risks and likely costs of launching such a massive war. From an expected value perspective, it was surely a losing gambit.

A big part of the reason they launched the attack anyway was that they believed that time was not on their side. They were being squeezed by the American embargo, and there was no prospect for victory in their war in China, only a grueling and costly stalemate. They needed to radically change their position if they were to have a chance of achieving their overarching war aims of hegemonic control of the western Pacific. Going for broke was, from that perspective, arguably a rational move.

It’s not hard to understand why Putin might see his situation similarly. His prior efforts to gain effective control of Ukraine had largely failed. The country was building up its armed forces with support from America and its allies. Russia, meanwhile, had probably reached the high-water mark in terms of its economic leverage via the energy markets. If he couldn’t achieve his goal of making Ukraine fully and permanently subordinate to Russia now, he might never be able to do it.

If that’s the case, then it might have been rational for him to launch the war—and to launch it the way he did, with a full-on invasion of the entire country—even knowing the rupture it would bring in Russia’s relations with other states, and even if there was a very good chance the invasion would fail. That’s particularly the case because we rarely estimate correctly just how badly our decisions could turn out. Japan’s leadership certainly didn’t anticipate an end game where its cities were bombed to rubble and the country was controlled by a foreign occupier. Similarly, it is quite plausible that Putin has failed to reckon with the possible costs in terms of the stability of his own regime if the war in Ukraine goes poorly. Just as a defensive war in response to foreign attack rallies the population around the flag, launching an aggressive war that goes badly is a classic contributor to regime collapse. It happened to the Czars, and it happened to the Soviets. It could happen to Putin’s regime as well.

The war doesn’t seem to be going poorly yet, of course; while Russia’s advance has been slower than initially anticipated, missiles are already falling on Kyiv, and Russian ground troops are already just north of the city center. It was never very likely that a Russian invasion would be stopped in its tracks—but that’s not the right metric for success in a war like this. The question is not whether Ukraine will be easily conquered, but whether it will be easily pacified. Answering that question with any confidence will take not days but months or years.

Which is why I’m not going to try to answer it. My only purpose in writing this post is to caution others not to assume that Putin knew the answer to it before launching his war. He might have had very little idea at all, and still believed it was time to go for broke.