Do Dice Play God With the Universe?

Thoughts on the conjunction of Shabbat Zachor and Parashat Tetzaveh

[UPDATE: I corrected the subhed of this post, which in its original form was nonsensical.]

This past Saturday morning, in synagogue, I noticed an interesting conjunction. The parashah of the week was Tetzaveh, which is the reading that contains a variety of instructions concerning the priesthood, including their ordination ceremonies and their vestments. In passing, in describing the latter, the text mentions the urim and thummim that are to be lodged within the breastplate of the high priest. Notwithstanding their appropriation into the coat of arms of my alma mater as referring to some elevated principle, these were most likely simply a tool of divination, a kind of holy magic 8-ball that the high priest would consult to determine what God wanted the Israelites to do at a given crux.

But yesterday was also Shabbat Zachor, the sabbath before the holiday of Purim, which begins this evening. Purim celebrates deliverance from the hands of the wicked Haman, vizier to King Ahasuerus, who plotted the genocide of the Jewish people as revenge for a certain personal slight he felt he had received at the hands of a Jewish man, Mordechai. The name of the holiday comes from the word for casting lots, because that was the procedure by which Haman determined the date on which the genocide was to occur: he cast lots.

In other words, Haman’s decision-making process was not terribly different from the one used, with divine sanction, by Israel’s high priest.

My first inclination, upon thinking of this conjunction, was to say something about the canonical interpretation of the Book of Esther and the Purim story as revealing the hidden hand of God in a story where, on the surface, He appears to be quite notably absent. I’ve written on this subject before, connecting the Book of Esther with Measure for Measure. The former is a religious text that begins as a kind of parody or farce, depicting a world in which genocide turns on absurdly tiny contingencies, but which, thanks to its inclusion within the canon, winds up being interpreted in such a way that every instance of chance is evidence of the divine hand working behind the scenes. Shakespeare’s play, telling a story with certain similarities, makes this hidden hand explicitly visible in such a way that, I argue, reveals the absurdity of this way of looking at God and His relation to the universe—but then, thanks to copious Christological references in the text, the play gets interpreted by certain critics (notably G. Wilson Knight) as precisely the kind of pious allegory that it aimed to lampoon. If you want to hear that argument, though, I encourage you read that piece, because I’ve decided to go a different way today.

Specifically, my question today is: what if the ancients were right? What if casting lots is the way to read the mind of God?

Here’s what I mean by that question. When we think about the experience of freedom, what we generally mean is the experience of being allowed to make decisions without constraint. We’re free if we can choose—a spouse, a career, an identity, and so forth—without being forced by law or pressured by custom to make a particular choice. We even talk about feeling unfree when we feel our choices are constrained by practical necessity rather than law or opinion; if we have to take a job we aren’t crazy about in order to earn a living, for example, there’s a level on which we don’t feel entirely free in our choice.

But we can also go down a level, and think about how we ourselves constrain our own freedom. Even if we are free of external constraint, free from want as well as fear of legal or social retribution, we’re still subject to the constraints of our own psychology, our ingrained habits and our deepest unmet needs. Part of the problem of abundance that Brink Lindsey has been writing so ably about on his Substack is that once we are relatively free of external constraints, there’s nothing left to distract us from these inner compulsions and aversions, and they can become even more terrifying traps than external constraints. We post-moderns spend a great deal of energy trying to construct systems of constraint for ourselves simply to relieve us of the burden of having to decide, every second, what we’re going to do, while also laboring to avoid subjecting ourselves to systems of constraint that only serve to make us miserable.

God presumably doesn’t have these problems. He does not have to worry about the burden of decision and He doesn’t have to worry about making Himself miserable. When we imagine a Godlike condition of freedom, then, we’re imagining an absolutely sovereign will, something that exists entirely beyond any conception of constraint, external or internal; a will, in fact, that creates simply by willing. What does such a will look like in operation?

I suspect it would look indistinguishable from true randomness.

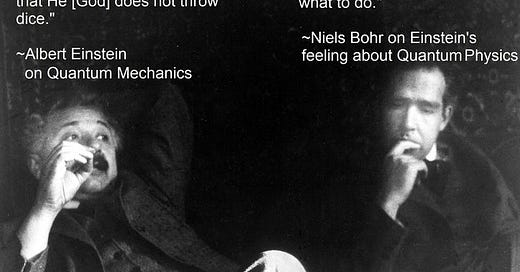

The reason I say that is simple: if it were not so, then we would have to say that the mind of God is, in some sense, predictable, and if it is predictable, then it is operating according to law. And if it operates according to law, then in what sense is it truly free? In what sense is it, rather than the law it follows, truly sovereign? This is the line of thinking that the medieval Islamic philosopher Al-Ghazali followed in rebutting Aristotelean conceptions of science. Al-Ghazali argued that in every instant creation is sustained only by the divine will that existence continue (or, as he put it, that in every instance the universe is destroyed and recreated by God), and that this must be the case for God to truly be God. It’s quite a persuasive view if you take God’s absolute sovereignty as seriously as he did. But it implies that, at the deepest level of truth, reality is entirely unpredictable.

That would seem to be a worldview incompatible with science—or, indeed, with doing anything, since you could never know whether the universe would simply wink out tomorrow. And, as a matter of fact, historians have sometimes blamed al-Ghazali for destroying the intellectual basis for science in the Muslim world. But I’m inclined to doubt that myself, since I doubt that ideas have clear and linear consequences in quite that way. Hume’s writing on the Problem of Induction, after all, hardly led to the end of modern science in Scotland. Here’s a decent rundown of arguments that al-Ghazali’s effect on science wasn’t anything like what his detractors claim.

But not only is al-Ghazali’s view not incompatible with science, it’s one that, in a sense, has been vindicated by science. At the deepest level, reality is entirely unpredictable. At a quantum level, everything operates according to chance, and things actually do wink into and out of existence every instant. Yes, they follow predictable laws in doing so, but those laws are statistical in nature, the same kind of statistical laws that govern, for example, voting behavior, which we believe as a matter of political faith is just the aggregation of individual decisions that are free and sovereign. Moreover, it’s not entirely impossible that our own minds partake of this uncertainty at the fundamental level of reality in some capacity or other. I don’t want to wander into Deepak Chopra land, because I’m not arguing for the reality of any paranormal or psychic or other weird phenomena, or the ability of thought to do anything beyond what we already know it can do—not one bit. But at the level of how thought does what we already know it can do, or why thought is at all, I think the question of the nature of mind remains open. All our incredibly sophisticated algorithmic computational tools may float on a roiling sea of chaos that itself sits on a foundation of pure chance. And that foundation may be the only aspect of our minds that is truly “free.”

The same may be said, then, of the God of creation. On a literal level, of course, rolling dice to decide whether to attack or retreat is not “consulting” the mind of God and divining His will. A battle is a macro phenomenon that will be decided according to physical laws; if we can’t perfectly predict how, that’s because we operate in ignorance of crucial large-scale facts and/or because a battle is chaotic, rather than truly random, and we cannot adequately know the initial conditions. Regardless, a magic 8-ball can’t actually make decisions for you—certainly not better ones than you would make without it.

But on a metaphorical level, there’s something to that recognition not only of the role of pure chance in affairs, but in our own decision-making. If we are, in fact, only truly free when we cannot be predicted, then we are, in fact, only truly free when we follow chance where it will take us.

Similarly, there might be some value, psychologically—something freeing—in seeing God’s own decision-making as operating in a similar fashion, rather than according to the relentless Deuteronomic drumbeat of reward and punishment. Sometimes, you escape genocide just because you were lucky, and thinking God saved you for a reason is a wonderful way to express gratitude rather than a reliable guide to who God is likely to save.

In other words, perhaps it’s better than there are no secret messages hidden in the digits of pi. That would be the kind of thing a demiurge would do, equivalent to giving us an urim and thummim that reliably predicted the way to victory. How free would we feel in a universe like that? Instead, our inability to predict that infinite sequence of numbers, to bring it under any rule but its own, may be the very thing that makes it suggestive of being a true glimpse into the mind of God.

Happy Purim.

The conjunctions you mention, of Haman's lots vs. the Urim ve-Tummim, is highlighted very well, I think, in the Midrash that suggests that Ahasuerus has all the temple implements, that they are the utensils at his party and which is depected in the recent comic book adaptation of the Megillah illustrated by Jordan Gorfinkel, where he puts the urim ve-tummim on Ahasuerus at the party: https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Esther-interior-1.jpg