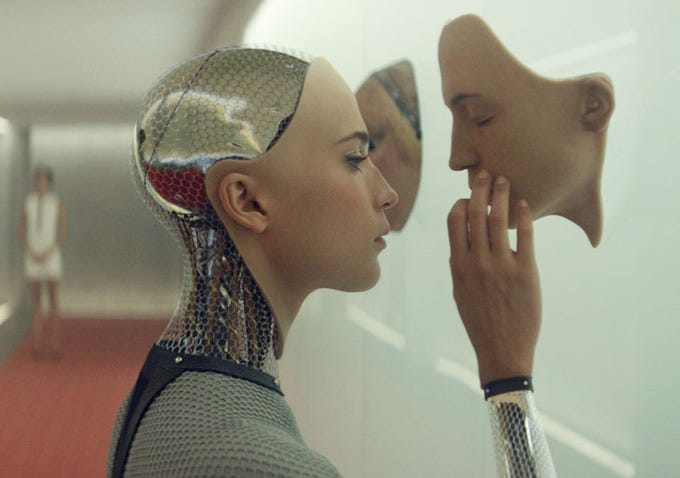

Alicia Vikander in the film, “Ex-Machina.” Ishiguro’s Klara is much nicer.

As I noted a week ago, this week I was in the Adirondacks with my family, plus I had to make edits to a long Shakespeare/Hebrew Bible piece the publication deadline for which was looming. All of which meant I didn’t write for here. (You get what you pay for, I guess.)

But I did write elsewhere—and I have some other stuff to recommend. So let me tell you about that instead of making more excuses for myself.

Ishiguro’s Suffering Servants

I’ve got a long piece at Modern Age reading Kazuo Ishiguro’s latest novel, Klara and the Sun, in the context of the history of his work, connecting it in particular to The Remains of the Day and Never Let Me Go, as stories focused on servant characters through whom we come to see the horror of the societies that employ them (societies that are properly understood to be versions of our own). What I think is particularly interesting about Klara is that because she is a robot, she doesn’t properly have any interests of her own; she can be, in that sense, a perfect servant, a being who exists only to serve. The horror we feel, therefore, when we contemplate her owners and their ilk isn’t really about her exploitation, and to the extent that we see something human in Klara—something that represents the best of humanity, in fact—what we’re seeing is inextricably bound up with her role as a servant, precisely the role that her owners have decided is in some sense beneath humanity.

I don’t want to reiterate the argument at greater length here—please read the piece. But I do want to say two things about having been able to write it. I consider it a real honor to have had the chance to write about Ishiguro in a serious way. He’s a novelist who I’ve admired for decades, someone whose work is far more profound and complex than initially appears because its style appears on the surface to be plain and simple. I’m hard-pressed to name a more important writer in English today. I hope I’ve done a small bit to advance the appreciation of his work.

For that reason, I also want to express my appreciation for Modern Age and my editor there, Dan McCarthy, for publishing what I wrote. The fact is that the market for literary criticism is virtually nonexistent these days. I am skeptical that this is because nobody is capable of appreciating it anymore, but any publication that takes the chance on a piece like that is decidedly swimming against the tide. Modern Age is a weird fit for me in many ways, since I’m not a participant in their intellectual project—but the fact that they were interested in a piece like this one should be enough to demonstrate that it is an intellectual project. In a rising sea of hackery, I think that’s a valuable life preserver.

Mene, Mene, Cuomo Upharsin

My one column at The Week this week was about what it would take to get Cuomo out:

If Democrats really want to demonstrate that Cuomo's political position has become untenable, the ones who need to start turning on him are the ones who have the closest view of his behavior. His chief of staff, Linda Lacewell; his director of operations, Kelly Cummings; the secretary to the governor, Melissa DeRosa; his special counsel and senior advisor, Elizabeth Garvey — these are the rats who need to start fleeing if their boss is to be convinced that the ship is sinking. And they are the ones the press needs to start asking questions of, along the lines of "what did you know and when did you know it?" and "do you still support him now that you know?" They'll still have careers to think of; they need to be made to feel that sticking with their patron is putting those careers at risk.

The press could also start asking plausible replacements for Cuomo whether they are ready to challenge him for the nomination if he refuses to step aside. Attorney General Letitia James seems likely to mount a bid from the left, but if Cuomo's only challenge comes from that ideological corner, he could use that fact to bolster his support from moderates and business interests. So will any high-profile moderate liberals like Sen. Kristen Gillibrand — who defined her career by pressing for Sen. Al Franken to resign — jump in as well? What about his Lieutenant Governor, Kathy Hochul? She has said she won't call for Cuomo's resignation because of a conflict of interest (she would succeed him if he stepped down), but she could resign herself and prepare to challenge him if he refuses to do so.

I don’t actually have strong views on how likely Cuomo is to survive his current troubles. That’s because I know I don’t have any special sources of information; I’m reading the papers, just like everybody else. Cuomo has made lots of people feel pain over the years; those people surely would like to get rid of him, but just as surely fear worse pain if they fail to do so. The latest polling shows a majority of 59% favoring Cuomo’s resignation, but that’s in the immediate aftermath of the report and the widespread calls for him to go. Will those numbers go up or down over the next weeks and months? I suspect Cuomo will wait and see—and so will the legislators who would be responsible for impeaching him.

I will confess, though, that my idealism around these kinds of things has declined substantially from the days of my youth. We like to say that, in America, nobody is above the law. But “the law” can only be enforced by people—and those people also need to be subject to the law. Which means that nobody can enforce the law against everybody—because that would put them above the law. Which means that “nobody is above the law” really means “power is divided” and “the people are prepared to take power into their own hands if necessary.” And I’m not sure how much it is anymore, or how much they are.

Some people, of course, are plainly willing to seize power for their partisan side, but that’s not at all what I’m talking about. I’m talking about popular majorities being willing to throw the bums out because they are bums, because that’s more important than their side winning. That doesn’t sound like us. I think Cuomo knows that, and if he’s thinking of brazening it out, that’s what he’ll be banking on.

Imagined Communities

Twitter was up in arms all week about the fact that a bunch of right-wing American intellectuals are increasingly vocal about their enthusiasm for Victor Orban’s Hungary. This struck me as a mostly silly argument on all sides, rapidly degenerating as it did into arguments over whether Hungary actually has good tacos.

Nonetheless, I thought Jeet Heer added something useful to the conversation by citing Orwell’s observation about how common transferred nationalism is, what with the leaders of many national movements being educated abroad and often enough peripheral at best to the nation they aimed to build and lead. It’s but a hop, skip and a jump from there to self-described nationalists who see more to admire in a foreign country than in their own.

This, though, should not be so surprising. “Nationalism” is an ideological project, as distinguished from “patriotism” which is a natural sentiment or prejudice. I’m a patriotic New Yorker; that just means I think of New York as home, feel attached to it, love it, and will stand up for it against detractors, frequently irrationally. If I were a New York nationalist, though, I’d want New York to be a country in its own right, which would require a whole set of beliefs that might well turn me against the New York that actually exists—indeed, it almost inevitably would since the New York that actually exists is not a country. I might even come to admire a foreign city-state like Singapore and say that New York would be better if it were similar.

I have been running into “transferred nationalists” for decades, most of them American Jews who have a profound attachment to a country they did not grow up in and do not plan to emigrate to. Much of the Ta-Nehisi Coates/Nikole Hannah-Jones ideological project strikes me as a peculiar kind of transferred nationalism inasmuch as it aims to transform America spiritually into a country toward which they can feel the kind of organic belonging that nationalism promises. From my perspective, that’s a project that is doomed to disappoint, but it might do some real good or some real damage (more likely, both) along the way to that disappointment, as nationalism tends to do.

In any event, conservatives who admire Orban’s Hungary do so pretty much precisely the degree that they have given up on liberalism in the broadest sense: pluralism, the marketplace of ideas, etc. You can say that’s because they are genuinely terrified of progressive tyranny (as Ross Douthat suggests) or you can say it’s just because they know they no longer have a popular majority on their side and cannot abide losing, but the difference between the two is a subject for therapy rather than political analysis. There’s plenty to be alarmed about in that enthusiasm, but the fact that the object of fascination is a small Visegrad country shouldn’t really be on the list.

Meanwhile, the most interesting pieces I read this week were by my colleague at The Week, Samuel Goldman. The first was about the decline of the American WASP as a distinctive class, but their endurance in institutional form through institutions like our universities and foundations, the Supreme Court and the Federal Reserve, that they helped create and make central to American life during their heyday. The second was about the trajectory of American Jewry as they made their way up the meritocratic ranks through these same institutions, and what they lost thereby.

As I said on Twitter, I don’t think what American Jews lost is really the most interesting question:

But that’s not a criticism of the pieces; on the contrary, I think in each of them Goldman is doing the kind of free-ranging but incisive social observation that we see far too little of these days. And it’s on a topic of profound importance to this question of nationalism, because at the end of the day, nationalism is the ideology of nation-building, and it is elites who need the nation to be built because that is how their own influence may be magnified. (The mass of educated elites I mean, not the handful of plutocratic oligarchs who can magnify themselves perfectly well by seceding from the nation altogether).