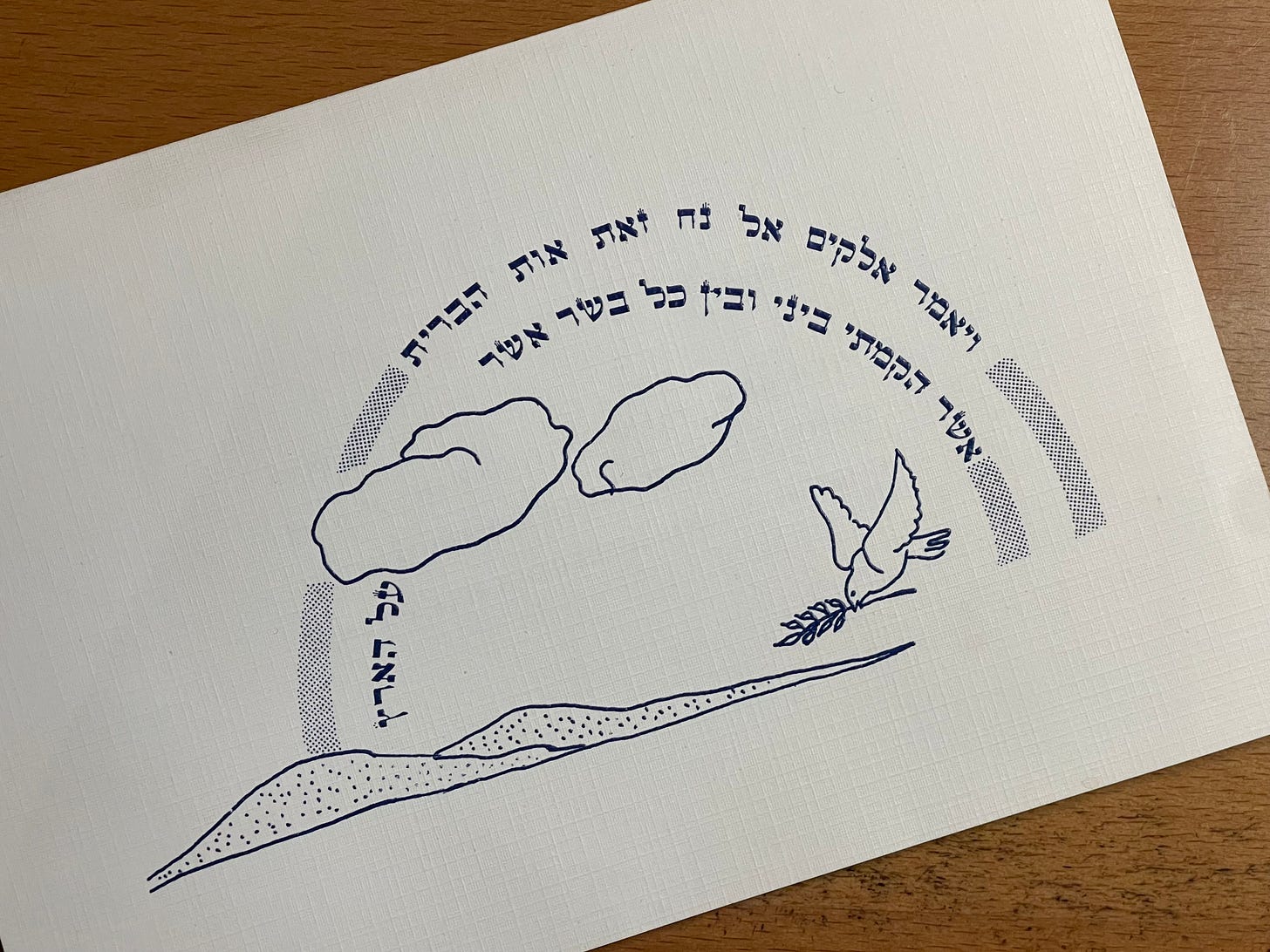

My bar-mitzvah invitation, designed by my grandfather

This past Shabbat, our rabbi was away celebrating a bar-mitzvah at another synagogue. So she asked me to step in and give the dvar Torah in her stead, which I was honored to do. This is the talk I delivered.

Noah is a parshah with a lot of meaning for me.

To begin with the obvious, there’s my name. Among Ashkenazi Jews, children are frequently named to carry on the memory of a beloved family member who is no longer living, but my mother, when considering a name for me, quite explicitly wanted to avoid that. Most of her parents’ immediate family had been murdered in the Shoah, you see, and she wanted to give me a name that looked forward rather than backward—a name that signified survival and starting over after catastrophe rather than remembering what had been lost. Noah fit the bill.

Needless to say, I had a lot of Noah-related paraphernalia in my room as a child. Of course, you don’t have to be named Noah to get Noah-related stuff for your child’s bedroom; a boat filled with animals is generally going to be a hit with kids. But if you’re actually named Noah, you relate to these childhood toys and decorations a bit differently, and when I reflected on it, as inevitably I did, I found the connection between Noah and childhood kind of weird. The story of Noah, after all, is a story of almost universal destruction—that’s why my mother chose the name—which is hardly obvious material for child’s play. Then again, kids, or their parents, routinely find ways to make games of catastrophe. My friend Joe, a recent American oleh, related a story to me recently about huddling with his young children in the shelter as rockets flew overhead. Hem lo tillim; hem pillim he said to his young children, “they aren’t missiles; they’re elephants.” So when one exploded relatively close by, the children laughed and shouted, “wow, that was a really big elephant!”

I also had lots of children’s books about Noah, one of which I remember quite fondly if vaguely after all these years, informed by all kinds of midrashic, aggadic and kabbalistic material, which I wish I could revisit but have never been able to find. A fun bit of trivia that I learned from that book: Noah was the first person to be born with fingers. Before that, according to the legend, people all had webbed hands, which made them clumsy, unable to do fine work. It’s a fascinatingly weird idea, that Noah was marked as different from birth—treated on the one hand as a freak, but on the other hand as a more evolved being, a harbinger of the future. Though, it has occurred to me since, webbed hands would have been very useful for swimming. Perhaps that’s why Noah’s neighbors disdained the ark he was building. Perhaps they thought only a delicate mutant like him would be unable to ride the coming waves.

The Shabbat after I was born was also parshat Noach, which may have helped seal the deal name-wise. It also meant that Noach was my Torah portion to study for my bar-mitzvah, which I celebrated forty years ago. One of the first things I remember learning when I began studying it was the rabbinic debate over Noah’s righteousness.

The relevant verse reads:

נֹחַ אִישׁ צַדִּיק תָּמִים הָיָה בְּדֹרֹתָיו

“Noah was a righteous and whole-hearted man in his generation.”

Did that mean Noah was exceptionally good, because he managed to be righteous in the context of such universal depravity that it prompted God to destroy the whole world? Or did it mean that only in such a context would Noah have been considered righteous, whereas in Abraham’s day he would barely have rated a mention? This was my introduction to rabbinic debate, and to the idea that these kinds of questions aren’t intended to have definite answers, but rather that each interpretation opens up a different way of understanding a text, a character, a whole world.

With time, I’ve come to see the question’s depth better than I did as a child. Ehud Barak once said that if he had been born a Palestinian he would probably have become a terrorist, and Abraham Lincoln lectured anti-slavery Republicans that had they been born in the South they would likely have views diametrically opposed to those they professed with such fervor. Those statements by Barak and Lincoln reflect quite a radical degree of empathy, but that empathy didn’t in any way hinder them in pursuing the righteousness of their causes, in peace or in war.

And now, parshat Noach has become significant to me for a new reason. This is the Shabbat before the first anniversary of my father’s death; his first yahrzeit begins this evening. I believe my father went to synagogue the Shabbat morning before he died, and if he did, then parshat Noach would have been the last Torah reading he heard. Inevitably, that knowledge will color my relationship with the parshah, since from now on, whenever this parshah comes around, it will be the Shabbat before my father’s yahrzeit. I was named Noah specifically as an alternative to dwelling on loss, but now Noach will always have a memorial aspect for me.

As it happens, this memorial aspect is built into the parshah itself. Every year, on Rosh Hashanah, I’m excited to read the zichronot section of the musaf amidah, because it’s one of the few times that I hear my name in the liturgy, which quotes this verse:

וַיִּזְכֹּר אֱלֹהִים אֶת-נֹחַ, וְאֵת כָּל-הַחַיָּה, וְאֶת-כָּל-הַבְּהֵמָה אֲשֶׁר אִתּוֹ בַּתֵּבָה; וַיַּעֲבֵר אֱלֹהִים רוּחַ עַל-הָאָרֶץ, וַיָּשֹׁכּוּ הַמָּיִם

“And God remembered Noah, and all the beasts, and all the cattle that were with him in the ark; and God caused a wind to pass over the earth, and the waters subsided.”

This is the standard formula the biblical text uses to talk about a miraculous turn for the better, repeated in the subsequent zichronot verses: God hears the Israelites’ cries in Egypt and remembers His covenant with Abraham, Isaac and Jacob; and, when the people of Israel are in exile on account of their sins, God will remember His covenant again—and the people will be redeemed. The zichronot section ends by recalling to God’s mind the akedah, the binding of Isaac, asking God to remember that horrible moment with compassion, and account it a reason to show compassion on all of us who are Isaac’s descendants.

The idea of having to remind God, or God having to remind Himself, is a paradoxical one given God’s omniscience, attested to right at the beginning of zichronot, where we declare: אֵין שִׁכְחָה לִפְנֵי כִסֵּא כְבוֹדֶֽךָ—“there is no forgetting before the throne of Your glory.” It is perhaps better to understand our prayers as prayers for selective memory, and hence, by implication, for divine forgetfulness. We are not praying that God remember everything about us, but that He remember the good things, and remember His covenant with us which endures regardless. Implicitly, we want Him forget the rest, so that we are treated with mercy and compassion rather than with strict justice.

But there’s another place in parshat Noach that speaks to remembrance, one that isn’t quoted in the Rosh Hashanah liturgy, likely because it has such a profoundly different feeling to it. It’s from the fifth aliyah, and it’s about the rainbow:

וַיֹּאמֶר אֱלֹהִים, זֹאת אוֹת-הַבְּרִית אֲשֶׁר-אֲנִי נֹתֵן בֵּינִי וּבֵינֵיכֶם, וּבֵין כָּל-נֶפֶשׁ חַיָּה, אֲשֶׁר אִתְּכֶם--לְדֹרֹת, עוֹלָם. אֶת-קַשְׁתִּי, נָתַתִּי בֶּעָנָן; וְהָיְתָה לְאוֹת בְּרִית, בֵּינִי וּבֵין הָאָרֶץ. וְהָיָה, בְּעַנְנִי עָנָן עַל-הָאָרֶץ, וְנִרְאֲתָה הַקֶּשֶׁת, בֶּעָנָן. וְזָכַרְתִּי אֶת-בְּרִיתִי, אֲשֶׁר בֵּינִי וּבֵינֵיכֶם, וּבֵין כָּל-נֶפֶשׁ חַיָּה, בְּכָל-בָּשָׂר; וְלֹא-יִהְיֶה עוֹד הַמַּיִם לְמַבּוּל, לְשַׁחֵת כָּל-בָּשָׂר. וְהָיְתָה הַקֶּשֶׁת, בֶּעָנָן; וּרְאִיתִיהָ, לִזְכֹּר בְּרִית עוֹלָם, בֵּין אֱלֹהִים, וּבֵין כָּל-נֶפֶשׁ חַיָּה בְּכָל-בָּשָׂר אֲשֶׁר עַל-הָאָרֶץ

“And God said: 'This is the sign that I set for the covenant between Me and you and every living creature that is with you, for perpetual generations: I have set My bow in the cloud, and it shall serve as a sign of a covenant between Me and the earth. And when I shall bring clouds over the earth, and the bow is seen in the cloud, I will remember My covenant, which is between Me and you and every living creature of all flesh; and the waters shall never more become a flood to destroy all flesh. And when the bow shall be in the cloud, I will look upon it, that I may remember the everlasting covenant between God and every living creature of all flesh that is upon the earth.'”

This is quite extraordinary. You might think that God would have put the rainbow in the cloud as a sign to humanity of God’s covenant, that we would know that God will never again destroy the world and start over. But that’s not what the text says. The text says that the rainbow is there for God, that He will look at it and remember His covenant, His promise not to destroy. The rainbow is like God’s tzitzit, God’s tefillin, God’s mezuzah, the sign that reminds Him of His obligations, as those are supposed to remind us of ours. As I say, it’s an extraordinary idea, that God needs such a reminder. I read it as a kind of maturation on God’s part, a moving on from perfectionism, from the impulse to tear up anything He created that isn’t everything He wanted it to be. It’s God recognizing that creation, by virtue of being creation, will always be flawed—in need of revision and repair, but not perfectible.

At the end of the sixth day of creation, God saw what He did and called it very good, and after that God made His first covenant, with Adam, giving him dominion over all of creation. But this new covenant that God makes after the flood, granting humanity a more terrible dominion over nature that speaks of fear and dread and not just mastery, is founded not on a conviction about essential goodness. Rather, it is founded in a recognition that human beings are, by their nature as created beings, endowed with a penchant to do evil as well as to do good, a penchant that cannot be expunged, only alleviated.

Noah, God’s choice for a new start after the flood, is described as tammim: “whole-hearted,” “innocent,” “without blemish”—those are some of the possible translations of that word. Yet the first thing that this ish tammim does after receiving his covenantal promise from God is plant a vineyard, make wine, and get so blind drunk that he collapses naked on the ground, where he depends on the compassion of his sons to cover his unconscious form. I don’t think it really matters why Noah took this turn—whether out of grief, which Noah must surely have felt for the world that was lost; or out of exhaustion, which he also surely felt after having to feed uncountable animals at every time of day and night for a whole year; or out of survivor guilt; or even out of an excess of joy and relief. What matters is that God makes no comment on the incident, not even after Noah is moved to curse the one son who dishonored him rather than treat him with compassion. God neither rebukes Noah nor promises to fulfill his curse.

When we pray to God, we ask Him to remember us for our good: to remember the times we were faithful to Him, the times that we sacrificed and suffered for His name’s sake, and the promises He made to our ancestors on whose merit we depend; and we pray for him to forget the times we fell down drunk and naked. But God’s reminder to Himself is something like the opposite. He’s reminding Himself that even when He sees and remembers our transgressions—indeed, even when we remind Him of the depraved generation of the flood in our violence and our cruelty—we nonetheless are His creations. He cannot despair of us. He has to work with us, because we are what He has to work with.

And that’s true for us as well. Whether we’re talking about our parents or our children, our fellows or our enemies—or our own selves—we have to build with crooked timber that cannot be made straight, because that’s all we have to work with. At the hardest times to do so, when the clouds cover the sky from horizon to horizon with nary a rainbow in sight, we have to remember that.

Shabbat shalom.

Re: the rainbow:

My gloss is a little different from yours. The rainbow comes after the rainfall and therefore after God has decided not to use this particular storm to destroy creation. It's a reminder, and maybe a reminder to Himself, but not a reminder "not to do something he's promised not to do" but a reminder to Himself, perhaps, that he has opted to honor his covenant.

I wasn't raised in the Jewish tradition, so my comment may be off in several respects. And to be honest, I haven't really thought about that story since I was a child.

At any rate, I appreciate this blog post, like I appreciate most of your posts. Thanks for writing it.

A Jewish friend of mine once told me that the Jewish people have a rabbinic story that, roughly paraphrased goes:

When Noah came out of the ark and saw the devastation that the flood had wreaked he said "Oh my God what have you done?" and God replied "Don't start with me, Noah, you were supposed to talk me out of it."

And this has always colored my understanding of the Jewish tradition of a people who have a relationship with (and sometimes an argumentative one especially) with God. It has also given me a much deeper understanding of the idea of Noah being considered -merely- "righteous in his generation" with, say, Job standing as a counter example.