Boudin vs. Krasner

Was there a difference between the two progressives? Or was it just a matter of time?

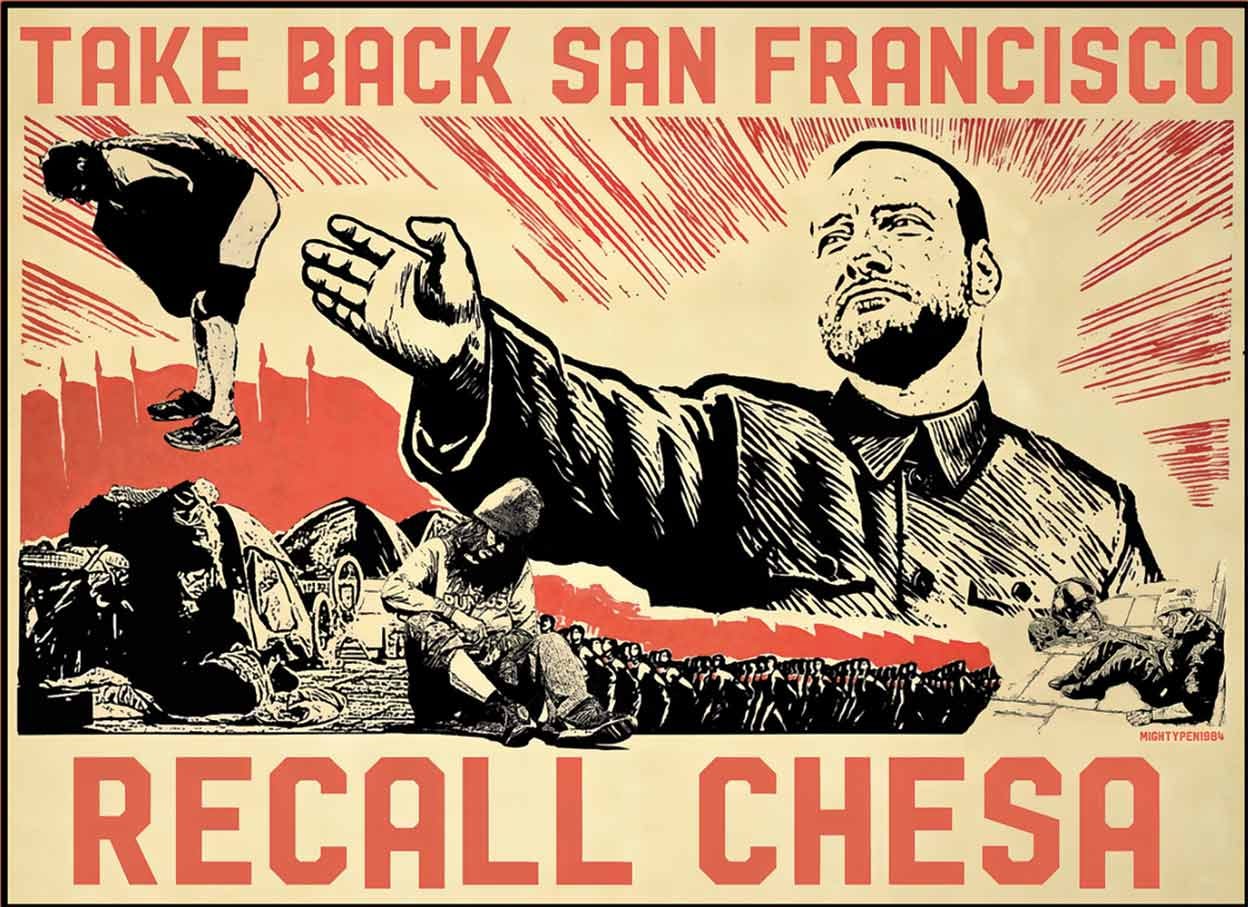

Chesa Boudin, San Francisco’s progressive District Attorney, was tossed from office decisively yesterday, in what is widely being reported as a rebuke to the cause of criminal justice reform. But it has only been a year since Larry Krasner, Philadelphia’s progressive District Attorney, crushed his primary challenger, setting him up for easy reelection in that overwhelmingly Democratic city. Why the dramatically different results?

It’s not that crime in Philadelphia isn’t a serious problem. On the contrary: crime in Philadelphia is alarmingly high and rising, and the electorate there is deeply concerned about it. Crime, drugs and public safety were overwhelmingly the highest concerns of Philadelphia residents, and both Black residents and residents of high-crime ZIP codes were especially likely to say that the police needed more officers to prevent crime and catch criminals. Nor is this a new development; violent crime was an enormous and growing problem before Krasner’s reelection, and was the context in which he won with the strongest support of residents of those same neighborhoods suffering the most from the high crime rate.

So what explains the difference? Progressive supporters of criminal justice reform have floated a number of unconvincing explanations for Boudin’s defeat: that the media manufactured a perception of rising crime among the San Francisco electorate; that big money supercharged a recall effort that lacked real popular support; even, absurdly, that San Francisco was always more conservative than Philadelphia, the city that dropped a bomb on MOVE. There’s a widespread tone of blaming an electorate that trusted their lying eyes which saw the deterioration of public order, and weren’t mollified by arguments that serious crimes like rape and murder weren’t up significantly. Whether or not those arguments are accurate, that’s never a useful way of coming to terms with a loss.

More plausibly, they’ve pointed out that a recall allows you to beat somebody with nobody, and that the demographics of San Francisco are very different from Philadelphia, with far fewer voters (particularly Black voters) who themselves worry about being victims of police misconduct. But Boudin effectively did have an opponent in Mayor London Breed, who has has rhetorically been running against him and will pick his successor. That dynamic isn’t very different from the one in Philadelphia, in which Mayor Jim Kenney blamed Krasner for not prosecuting gun crimes. Moreover, Krasner’s opponent was hardly a right-wing firebrand but a veteran former ADA who ran basically as “I’m not Krasner,” and the Democratic Party declined to endorse Krasner in his primary battle, whereas the institutional party (apart from Breed) largely backed Boudin.

As for demographics, it’s worth thinking about what that implies about the cause of criminal justice reform. San Francisco is majority non-White, but it’s only about 5% Black, and its few predominantly Black neighborhoods vote less-progressively than the city as a whole. The most progressive part of the city is the area around the Mission that is made up predominantly of White and Hispanic renters, and this is where Boudin retained his largest core of support. I’d venture to bet that this demographic is a smaller electoral force in most American cities than it is in San Francisco. If they aren’t enough for Boudin to survive there, where are they likely to be? If the answer is only “cities with very large Black populations and poor relationships with the police” then the prospects for widespread criminal justice reform are quite limited.

Many of Boudin’s defenders have argued that his office can’t reasonably be blamed for many of the problems for which he was tossed out of office. In particular, they point out, skyrocketing rates of homelessness are the result of California’s acute housing shortage and concomitant soaring rents, which push marginal renters into shelters and other temporary housing, and push longer-term homeless onto the streets. It’s also true that Boudin doesn’t run the police department; inasmuch as part of San Francisco’s deterioration is related to cops stepping back from enforcement in contravention of policy, that’s not something Boudin can solve directly. But these are less excuses than additional problems for the criminal justice reform movement. If other parts of the political system don’t address homelessness by expanding housing, then it will become a problem of public order, and if policing does deteriorate in the face of reform efforts, that will effectively cause reform to fail. Criminal justice reformers who want to succeed, practically and politically, need to demonstrate that they can respond to these contingencies and not just point fingers at them.

Which is another way of saying that they need to win over more conservative voters: middle-class homeowners who worry more about public order than they do about possibly being caught up in America’s often-Kafkaesque criminal justice system. Not convince them that they care about the wrong things: convince them that they you also care about the things they care about, so that they trust you when you say they should also care about the things you care about.

And what about Krasner? His last election demonstrated fairly convincingly that he had built a political base of his own, something Boudin never really tried to build in the same way. But no base is impregnable, and while conditions in Philadelphia were bad enough a year ago, the longer they stay bad the more open the Black voters who stood by him then will be to an alternative. In Philadelphia, a core public-safety issue is the widespread availability of illegal guns; getting them off the streets without more aggressive policing is a very hard nut for reformers to crack. If Krasner’s primary were held today rather than a year ago, I do wonder whether his opponent might have gotten more traction by pressing on that very point.

New York’s progressive prosecutor, Alvin Bragg, is already reading the writing on the wall and tacking to the center. I wouldn’t be surprised to see others do the same. If they can do that, combining continuance of their most important reforms with visible efforts to tackle rising crime and disorder, they, and their movement, might well survive. If they try running against their own electorates instead, they likely won’t.