Are "Movies For Grownups" On Their Way Out

On the verge of making my own, my confidence that they aren't begins to waver

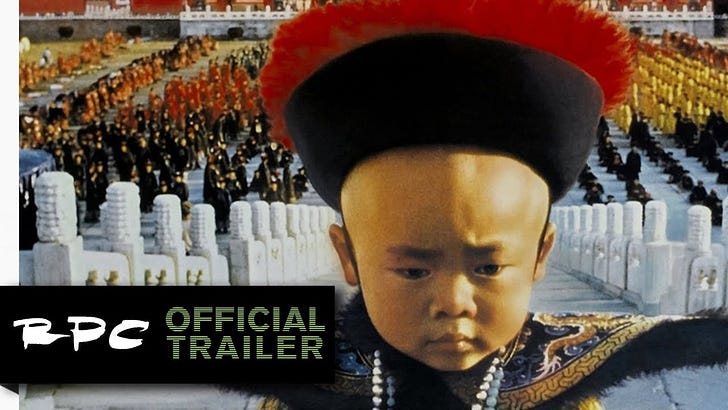

Trailer for The Last Emperor, winner of the Oscar for Best Picture in 1987

We’re coming to the end of the last quarter of the year, the period when Hollywood traditionally releases a host of movies with “awards potential,” and this year has been no different in that regard. Major films released since October with an eye on Oscar include The Banshees of Inisherin, The Fabelmans, Tár, Glass Onion, Emancipation, She Said, All Quiet on the Western Front, Till, Devotion, Armageddon Time and The Whale with Avatar: The Way of Water, Women Talking and Babylon still to come before year end—and there are probably more films to list that I’ve neglected to mention.

The calendar is as full as usual—but the theaters aren’t. With the exception of Glass Onion, which did extremely well in its brief theatrical release, and the Avatar sequel which is expected to be the kind of massive blockbuster that only James Cameron can reliably deliver, this has been a truly horrific box office season, prompting a new round of articles like this one wondering whether “movies for grownups” are simply no longer theatrically viable.

It’s a subject I’ve written about before, here and here and here and no doubt elsewhere as well. My usual take on this is that movies have gotten small for a reason, and we just have to live with it. Many of the structural reasons are articulated well in the Times article I linked to in the previous paragraph. The big one is that people’s habits have changed. They are staying home far more than they used to—playing poker at home, going to religious services at home, looking for romance (via apps) at home—and they spend more time alone as well. People still go out, but it’s more of an event and less something you just do as a matter of course, and so the only movies most people are going to are those that can be construed as events. And movies in particular have trouble motivating people to go out because you can stay home and have a great experience watching on a big screen at a time of your convenience and for less money.

Hollywood noticed these trends long ago, and adjusted their marketing and distribution plans accordingly. Theatrical runs are now generally extremely short, since a film that doesn’t quickly become an event is presumed to be a flop, and marketing campaigns are curtailed as well for any film that doesn’t quickly show promise—with the consequence that many moviegoers don’t even know what films they’ve missed the chance to see in theaters. All of this was happening before the pandemic, but COVID turbocharged these preexisting trends.

I don’t think that’s the whole story, though. Right near the beginning, the Times article confidently declares that “the problem is not quality,” and cites critics’ reviews as the proof. But critics are not some neutral barometer of “quality” and besides, the quality that actually matters is of being appealing to a mass audience today and of having that appeal endure over time. And I think there are good reasons why fewer movies aimed at “grownups” today are meeting those criteria than even in the relatively recent past.

For one thing, those same changes in habits that have so much movie-watching happening at home have changed the way movies are made, and the way filmmakers think about their medium. Most movies are directed now to work on a (relatively) small screen rather than to require a big-screen experience. Putting movies next to television, and the dramatic expansion of television as a medium, has also changed the way people relate to movies as narrative art, which has required filmmakers to change. Television can spin out a narrative over much longer, but television is also a much more explicit medium, not given to meditation. In most cases, movies have changed to match, and because a film’s canvas is smaller even though the screen is bigger, they have often become less compelling as a result. In other cases, though—and I think this is particularly true for certain kinds of prestige films—directors have tried to differentiate themselves more clearly from television by becoming artier, which naturally enough makes them less compelling to a large audience. Tár, I think, is a good example of this phenomenon; I’m not at all surprised that it is struggling at the box office, because it is a weird and difficult film (indeed, one that is weird in difficult in certain ways that I’m not convinced were necessary or good, though your mileage may vary).

The depressing economics of film also take their toll on the art. Certain costs of filmmaking have gone down significantly: cameras are cheaper and vastly more capable, which in turn makes it possible to shoot with less complicated lighting, and of course physical film and all its associated costs has largely vanished. But other aspects of filmmaking have gotten more expensive—specifically: people. Watch a film from a few decades ago and it’s amazing how populated it is relative to most films today. Productions also had far more time to shoot than films typically do now—and that’s again largely because personnel costs have soared; the more days you shoot, the more days you have to pay your cast and crew. But it’s harder to tell large-scale stories without having a lot of people in the cast—and it’s harder to make movies that are truly cinematic if you don’t have the time for complex shots and choreography.

I suspect the culture war has also taken a serious toll on film’s cultural influence. Film simply isn’t as central to the culture as it once was, which inherently limits its ability to reach and affect a mass audience. But our culture is also far more fragmented than it used to be with people increasingly siloed in their distinct affinity-based niches. Necessarily, fewer projects are likely to have appeal across these proliferating divides. Add onto that the deep fissures between urban and rural regions, and between more and less educated people, and you’ve narrowed your potential audience further. Finally, Hollywood has long flattered itself that its prestige films were not only artful but socially worthy, but contemporary sensibilities have made earning those particular laurels a grueling gauntlet that seriously inhibits the creation of art.

So has “quality” declined? Well, take a look at Variety’s list of the thirty films most likely to win the Oscar for Best Picture. Now compare that list to the nominees for Best Picture in the 1980s—a decade I chose because it is widely regarded as a relative low point for Hollywood artistically between the revolutionary 1970s and the indie-fueled 1990s, a time when the rise of the blockbuster had eclipsed films of serious artistry. Some of those nominees are blockbusters: Raiders of the Lost Ark and E.T. most prominently. Others are small canvas dramas: Ordinary People, On Golden Pond, My Left Foot. There are films that are revered by cinephiles: Raging Bull, Tender Mercies, The Last Emperor, and there are more crowd-pleasing films that continue to please: Tootsie, Broadcast News, Working Girl. There are also films on the list that are largely forgotten, or that many people wish to forget. But ask yourself honestly: which films this year feel obviously—obviously—like they would have deserved to be nominated for Best Picture if they had been made thirty-five or forty years ago ahead of the films actually nominated then? I’m not asking to put them up against The Godfather or Taxi Driver. I’m asking to put them up against Chariots of Fire, The Mission and A Room With a View.

Last year’s Best Picture winner was CODA, and I enjoyed that movie. Just to put it up against movies from the 1980s that might be deemed “worthy” for tackling similar themes related to disability, I can squint and see why someone might prefer it to Rain Man, or even to Children of a Lesser God, though I think that might reflect more of a presentist bias than the person so-preferring might be willing to admit. I can’t really imagine preferring it to My Left Foot or The Elephant Man. But compared to all of those 1980s films, CODA is transparently smaller in scope, less of a movie. That’s a quality, too, and it’s a relevant one to the survival of the medium.

This is all very personally relevant to me. As I’ve mentioned a number of times here, I’m in the process of gearing up to direct my first feature, an independent film drama. If all goes according to plan, we’ll shoot in March. I’m making it because I love film. In writing it, I was inspired by films like Carnal Knowledge and sex, lies and videotape, and I want to believe that there’s still an audience for films like those because there is still an audience for those films. My film is a small one, which is appropriate for a first feature, but it’s also a scale that I treasure; many of my favorite films are small ones. And yet, while artistically I think it’s fine if the films get small, I worry that the theatrical ecosystem can’t survive a transition of that kind, that indie film is only economically viable in a world where studio films for grownups are viable.

So to console myself I recall that as recently as just before the pandemic, I saw films in the theater that had scope and artistry and that could plausibly be remembered for many years to come—and that had financially successful theatrical runs, even overwhelmingly profitable ones. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Ford v. Ferrari and 1917 all met that description, but so did the less obviously populist BlacKkKlansman and The Favourite. Indeed, only five years ago, every single film nominated for Best Picture, from the small-scale Get Out, Lady Bird and Call Me By Your Name to mid-budget films like The Post and Darkest Hour, to the big-budget Dunkirk made more at the box office than it cost to make. Even the extremely arty Phantom Thread (which I loved) made money. And every one of them (except the Best Picture winner, The Shape of Water) was a film for grownups.

That wasn’t that long ago. The people making and watching those movies are mostly still around. Surely it isn’t impossible to imagine them getting back together again, and in the theaters.