Are Immunity Passports Something to Worry About?

Probably not -- but they aren't much of a public health measure either

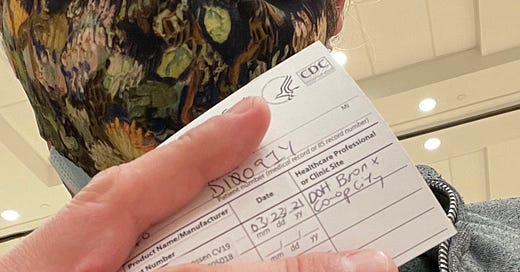

I got my COVID-19 vaccine the first day that I was eligible to do so in New York State (based on my age). Immediately, I began thinking of all the things I’m going to be able to do: have people over, eat inside restaurants, go to the theater (when they are open again). I bought my first tickets for an indoor, in-person concert for about a week after my vaccination becomes fully effective.

So from my selfish perspective, when New York State announced that they were going to experiment with the idea of immunity passports, I thought: great! I’ll be able to do more normal things more quickly — exactly what I want!

That reaction should tell you, though, what the purpose of such an experiment would be. It’s not really a public health measure. Rather, it’s a measure intended to enable more of the economy to open up more quickly. Whether that makes it more reassuring or more disturbing in terms of the precedent being set depends on your perspective.

Why do I say immunity passports — by which I mean: some document that would demonstrate that the holder had been vaccinated — are not really a public health measure? Because right now not everyone who wants to get vaccinated has been vaccinated, or even can get vaccinated. New York State just expanded eligibility to the vast bulk of the adult population, dropping the age requirement to thirty, and expects to drop it to sixteen within a week. But New York doesn’t yet have the capacity in terms of physical vaccine or delivery systems to provide a shot to every eligible person as quickly as they might want it. If the goal is to get more people inoculated more quickly, we need to expand that capacity (which is happening), and then we need to make the vaccine “cheaper than free” by bringing it to people who are relatively less-well informed, less-mobile, have less flexible work schedules, etc.

From a civil liberties perspective, immunity passports are not really a big deal; the government has the clear authority to simply force you to get vaccinated if it wants to, which is much more invasive than giving you the option of telling businesses your vaccine status. But there is a lot to do before we start talking about taking any punitive measures to convince the vaccine-hesitant to get the shot (and the size of the vaccine-hesitant population is shrinking steadily as evidence of the vaccines’ safety and efficacy mounts).

Nor is the purpose of an immunity passport to further restrict the lives of those who have not yet gotten a vaccine. Nobody is seriously talking about requiring you to show your health papers to go to the local grocery store. If enacted today, such a requirement would prevent most people from buying food, which would be obviously catastrophic, and once the vast majority of the population is vaccinated, requiring everyone to present such documents all the time would just be introducing unnecessary friction for the overwhelming majority of businesses and customers.

The purpose of an immunity passport, then, would be to enable activities that are unsafe and also non-essential — like going to a nightclub — to open to vaccinated people only, and thereby open them more quickly and/or with larger capacity while only a fraction of the population is vaccinated. They’re also a plausible mechanism to facilitate the restart of international travel, since receiving countries could dispense with quarantine requirements for travelers with demonstrable immunity. That’s why I say the idea of immunity passports is fundamentally about the economy, not about protecting public health.

That doesn’t mean they are a bad idea, necessarily. Reopening the economy is important, and state and local governments are already pushing ahead with that process in ways that are likely fueling a new surge. Moreover, it’s perverse to restrict everyone’s activities because we don’t want to discriminate against those who choose not to be vaccinated. As for privacy concerns, well, international travelers couldn’t keep much private in the pre-pandemic era.

Personally, based on our experience to date with contact-tracing apps and vaccine-priority lists, I am not sanguine about our ability to deliver such a document in a timely enough fashion for it to make a real difference in the pace of reopening, and that therefore the point will be largely moot. If we stall out well short of herd immunity, though, that calculus might change. If the pace of vaccination slackens significantly once we pass 50% or 60% of the population, as has happened in Israel, then we might legitimately worry about the economic cost of keeping restrictions in place while also worrying about the public health costs of lifting restrictions. In those circumstances, immunity passports might start looking quite appealing.

Which is precisely why I do worry a bit about them. It might seem like immunity passports are a way of pressuring people to get inoculated — get the shot and you can take a cruise! — but they are also a way of relieving the pressure on the state to achieve adequately high rates of inoculation to truly end the pandemic. Once life has gone back to normal for those with immunity, will the public still demand the kind of proactive measures — including entirely non-coercive ones like sending roving inoculation teams out to isolated areas, or to the homeless — to truly get to near-universal vaccination? Or will we give up on the last mile of the marathon?

I’m not sure — and for that reason, I want it to be clear just what an immunity passport would be for. It’s not a way to end the pandemic faster; it’s a way to get the economy moving faster. The latter is a completely legitimate goal, so let’s pursue it with vigor. But let’s not lose sight of the former goal’s primacy.