Don’t blame me; I voted for the squirrel

I’m a middle-aged Jewish guy who lives in brownstone Brooklyn, and for all my political idiosyncrasies that I am so attached to, I am functionally a moderate Democrat. I know a bunch of other middle-aged Jewish folks who also live in brownstone Brooklyn, so I know a lot of people who functionally fall into a similar political bucket. Which is to say: I know a lot of people who are not happy about the idea that they might have to choose between Andrew Cuomo and Zohran Mamdani in the New York mayoral primary. Some of those people I know have asked me how I’m voting, or how I would advise them to vote. Should they rank Cuomo last? Or Mamdani last? Or leave both of them off?

My advice lately is: it doesn’t matter. Whether you choose Cuomo or Mamdani—or whether you prefer to rank neither—you’ll likely get another chance to try again!

Why? Because if Mamdani loses to Cuomo in the primary, he will likely run in the general election on the left-wing Working Families Party line. And if Cuomo loses to Mamdani, he will likely run in the general election on the Fight and Deliver Party line that was created expressly for that purpose. Unless Brad Lander or Adrienne Adams pulls an extraordinary upset, consolidating the “neither Cuomo nor Mamdani” vote to win the primary on the ninth round, the general election is going to be a rematch between the top two primary finishers. So who cares who wins the primary? If you don’t want either of them, vote for neither, and kick the tough choice to the general election!

Now, it’s not really true that the primary doesn’t matter, because the Democratic line probably still matters. If Cuomo loses it, yes, he can run on a novel party’s line, and he’ll have the name recognition to make a race of it. But Mamdani will have the Democratic Party blessing and the backing of nearly every non-Cuomo candidate who ran in the primary. That should make him a more formidable general election candidate than he would have been on the WFP line, particularly for low-information loyal Democrats, of which there are many in New York. Winning the Democratic primary is the best way for Mamdani to translate a strong showing among the most committed voters into a general election victory.

But just because the Democratic line is valuable doesn’t mean it’s valuable enough to deliver a general-election majority in a five-candidate race—or even a victory. Mamdani could win the primary and then discover that, unlike in the primary where most of the field was beating up on Cuomo while cross-endorsing with him, Cuomo, Mayor Adams, the Republican Curtis Sliwa and the independent candidate Jim Walden will all be denouncing him for being totally unprepared and running on a lunatic platform. Cuomo—the man who in this scenario Mamdani beat in the primary—could wind up seizing the center and winning the general election. The opposite could also happen. Mamdani could lose the primary by a whisker and, even though he’d subsequently be running on the WFP line, run a positive campaign that both consolidates the progressive vote and reassures moderates, while Adams and Cuomo bash each other relentlessly, split the Black vote that will be so important to Cuomo in the primary, and remind voters generally why they are both so widely disliked. (Adams could even wind up winning, as I speculated previously in this space.)

Mamdani winning after losing the primary may sound implausibly far-fetched. How could the far-left candidate do better in the general election than in a Democratic primary? But I didn’t say Mamdani would do better in that scenario. I said there’s a scenario where he could win. Winning wouldn’t require doing better than his losing percentage in the primary—because victory in the general election will go to whoever earns a plurality of the vote, whereas victory in the primary will be decided by ranked-choice voting.

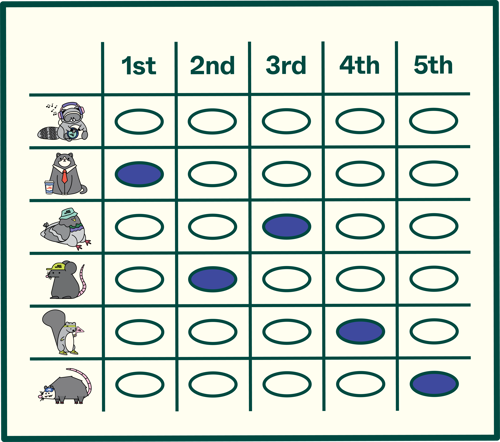

Suppose the first round of voting gives Cuomo 42% and Mamdani 35%. (The latest non-partisan poll shows a larger gap of 38% to 27%.) And suppose the final tally after allocating all the other candidates votes gives Cuomo 52% and Mamdani 48%. That’s a clear but not overwhelming Cuomo victory. Now comes the general election—and the final tally is 32% for Mamdani, 30% for Cuomo, 22% for Adams, 11% for Curtis Sliwa and 5% for Walden. There’s no allocation of Walden’s or Sliwa’s or Adams’s votes to see who their voters chose for second place. There’s no runoff. Mamdani will be the next mayor, even though he got less than a third of the total vote, even though he got less than he got in the first round of the primary, and even though, through ranked-choice voting, we know that Democratic primary voters preferred Cuomo, and needless to say we know that the Democratic primary electorate is more left-wing than that of the general election.

What kind of democratic mandate would anyone elected in such a fashion have? Not much of one. Of course, you don’t need a mandate to wield power—but those inclined to resist Mamdani would be profoundly emboldened by knowing that he was not a majority of New Yorkers’ first choice. It’s hard to imagine Mamdani would get much done, and easy to imagine instead that his elevation in such a fashion would inspire moves to eviscerate the mayoralty and move as much power as possible to Albany.

A similar pall of illegitimacy would mar a Cuomo mayoralty achieved by comparable means. If Mamdani won the final round of the Democratic primary, then lost the general election to Cuomo whom he beat, and Cuomo won with only a small plurality, then progressive voters—and the progressive majority on the city council—would declare the result obviously undemocratic. They would do everything in their power to hamstring a Cuomo administration before it got off the ground—or to force him to adopt left-wing policies that his entire candidacy was built around abjuring.

Ranked-choice voting has a number of virtues, one of which is that the winner definitely gets a majority of the vote (though not necessarily of the first-choice vote). But by combining ranked-choice voting in the primary with plurality-victory voting in the general election, and then by allowing sore losers to run in the general election on another line, New York has created a situation where not only the winner but the majority winner in the first round could lose in the general election to the same person they already beat, even if that person got a far lower percentage of the vote in the second round than they did in the first.

That’s not just a recipe for a weak mayoralty; it’s a recipe for discrediting democracy. And we really don’t need any more of those these days.

Here's another scenario: Cuomo wins the Dem primary and the WFP gives Lander its line because in the general election he's a more plausible alternative to Cuomo for centrists than Mamdani. Lander can consolidate Mamdani, Kathryn Garcia, Wylie factions, and drain enough disaffected E Adams voters to form an ad hoc plurality coalition that that would elude Mamdani on the WFP line and beats Cuomo.

"it’s a recipe for discrediting democracy."

Not really. It used to be that winning the Democratic primary was tantamount to winning the general mayoral election. As a result, only registered Democrats played a meaningful role in the election.

What needs to occur is the practice of ranked choice voting needs to be expanded to the general election (or some other method to replace the first-past-the-post system now used).