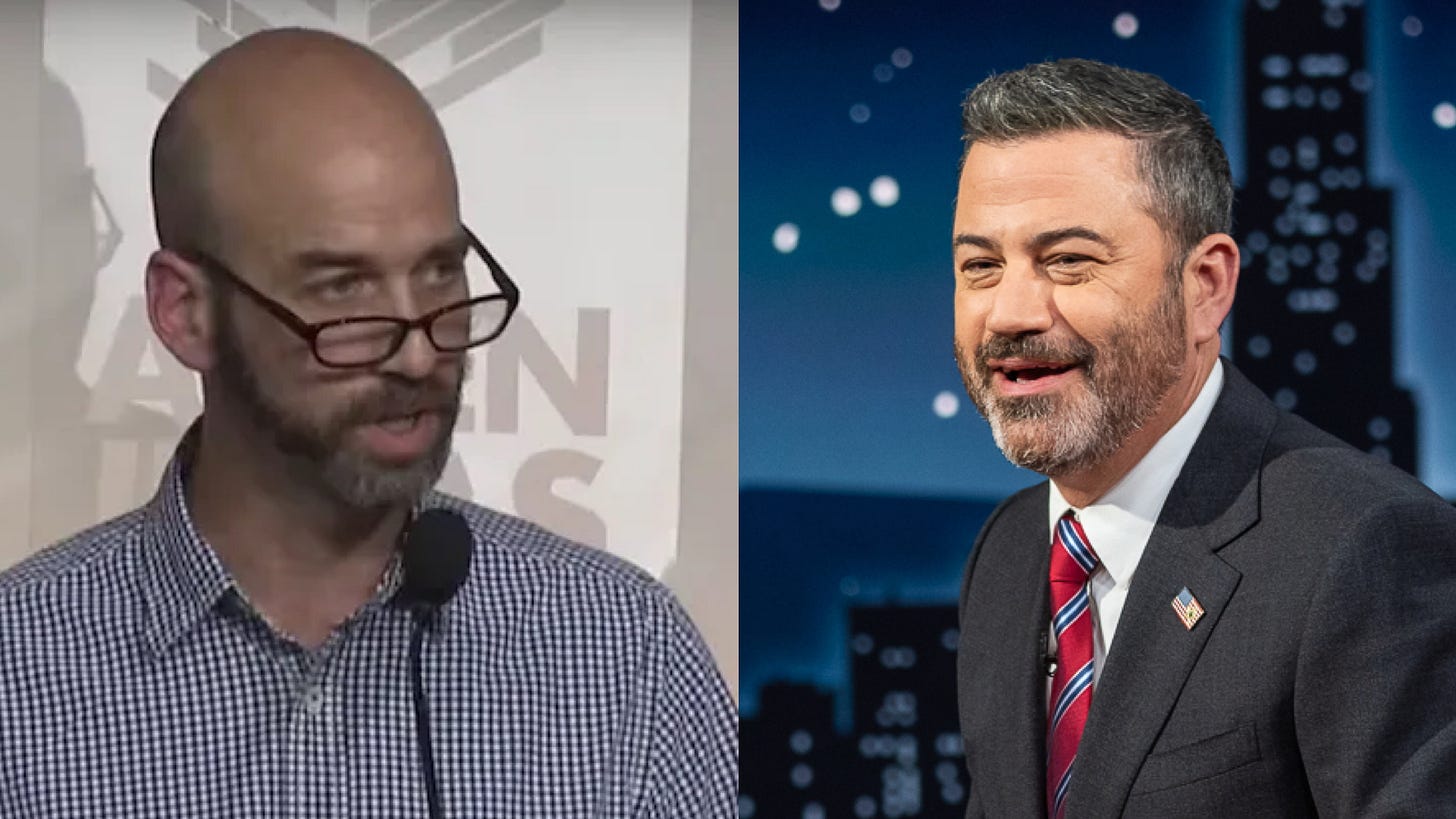

A Tale of Two Jimmies

Why Jimmy Kimmel's firing is making me think of James Bennet

On Wednesday, Brendan Carr, head of the FCC, issued an extraordinary threat against ABC and its parent company, Disney, that if they didn’t remove Kimmel in response to his on-air comments about the murder of Charlie Kirk, his agency would take regulatory action. Within hours, ABC decided to pull Jimmy Kimmel off the air. I could have thought of a lot of things—the blacklist against Communist-affiliated writers in the 1940s and ‘50s, the post-9-11 declaration by Ari Fleischer that Americans need to “watch what they say,” or the way threats to the independence of journalism have unfolded in Victor Orban’s Hungary. But the first thing I thought of was the defenestration of James Bennet in 2020 from his position as opinion editor at The New York Times. Why? Because I think these two events are connected in a profound and far-reaching way.

I should probably remind my readers who Bennet is and what happened to him. In June of 2020, when the Black Lives Matter protests and riots were at their peak, Bennet ran an Op-Ed by Senator Tom Cotton arguing that the president should send in the armed forces to quell the riots and restore order. The piece generated howls of outrage from members of the Times staff, with some claiming that merely running it put their lives directly in danger. To quell the staff revolt, the paper’s publisher, A. G. Sulzberger, asked Bennet to resign, justifying that demand by saying that proper editorial processes were not followed in the course of soliciting, editing and printing the essay. New procedures were put in place, for better or worse, but meanwhile a precedent had also been set which cast a shadow that persists at the paper to this day, the precedent being that the paper would cave to pressure.

The moment has long served as a synecdoche for me of the burgeoning left-wing illiberalism of the era. There’s no reason to think that Bennet had anything less than the full confidence of the publisher before the incident. And there’s no reason to think that Sulzberger himself was outraged when he read the editorial. While right wing commentators frequently imagine there was some nefarious conspiracy behind the extremity of that period, the reality is that it was a kind of popular madness that built over the course of years and finally exploded with the death of George Floyd.

That madness faded after 2020, though it hasn’t gone away, and the precedents that conservatives point to today to justify Trump’s extraordinary escalation are actions taken by the Biden Administration—like debanking and coordination with social media companies on preventing “disinformation”—that may certainly draw fierce criticism but that don’t have much if anything to do with the defenestration of James Bennet. So why do I connect the two Jimmies? Not because I believe left-wing radicalism is such a powerful threat today that it requires a heavy-handed government response to quash, First Amendment be damned. The pressure from the FCC that led to ABC’s decision was entirely unjustified, and incredibly chilling. Charlie Kirk’s killer may well have been radicalized in left-wing spaces—the initial evidence does seem to suggest that he was motivated by a desire to end Kirk’s supposed campaign of “hate,” specifically against transgender individuals—but it’s not like the right lacks for deranged radicals of its own and, as John Ganz ably put it in the piece of his I linked to in my last post, “the only state that could guarantee that something like Kirk’s murder never occurs again would be felt, with justification, to be an intolerable tyranny by nearly everyone in this country.”

No, the connection I’m making is a different one. Bennet was asked to resign for the “crime” of having published an Op-Ed by a sitting United States senator that many members of the newspaper’s staff took issue with. The publisher, in effect, abdicated his authority, giving an editorial veto to people he could easily instead have fired or simply ignored, which, if he wanted to uphold the image of The New York Times as a bastion of liberalism properly understood—caring about free enquiry and open debate—he most certainly should have done.

I don’t know whether it’s best to describe that abdication as cowardice, lack of conviction, or a simple discomfort with authority as such. There was a lot of all three floating around in 2020. In particular, I think a lot of people in formal positions of authority turned out to have a hard time saying no to people who they thought of metaphorically as their children. But when people in authority give in to pressure that they have the clear formal power to resist, and that they should resist if they believe in their own ideals, those who don’t share those ideals will notice. Notice they have, and I believe we are reaping the whirlwind now.

President Trump is a bully by nature. He exerts pressure in all directions to assert his dominance because that’s what he does. Even at its high tide, left-wing illiberalism had virtually no formal power. But informally, it exerted a great deal of influence, because America’s liberal institutions—news organizations, universities, cultural centers, etc.—advertised their weakness, cowardice and eagerness to appease. Now that the tide has receded, and right-wing illiberalism has acquired a great deal of formal power, all those character flaws are just as manifest as they were before. It’s no surprise, then, that a network like ABC folded so easily. They and organizations like them had folded to much less potent threats only a few short years ago.

Again, I want to be clear. I’m not comparing the pressure that Sulzberger faced from an angry staff to the pressure that ABC faces from the Trump administration. The latter is much more serious than the former, and the threat to the First Amendment is explicit in the latter case, while the former only implicates the culture of liberalism, not the guarantees of the Bill of Rights. But that’s my point: the fact that institutions folded in the face of relatively weak pressure, and refused to articulate the requirements of a liberal culture to those who claimed to believe in one, showed how much weaker they would prove in the face of more serious pressure from a more powerful opponent.

As a consequence, even those institutions that have stiffened their spines cannot credibly do so in the name of liberalism unless they confront their own recent history. They have to stiffen their spines anyway, of course. The New York Times has to refuse to knuckle under to baseless lawsuits, no matter what the cost. But they’ve got to rebuild their own authority to do it. If they don’t want to do it the way The Washington Post has, by bringing in a whole new team to reorient the paper in a center-right direction, they nonetheless still have to do it somehow. They have to not only reaffirm their fidelity to liberal values; they have to demonstrate that the grownups are in charge, and are going to stay in charge from now on.

Two other points:

First, I suspect that Matt Yglesias is right that the administration’s overreach into outright Orbanism is going to prove extremely unpopular, and unpopular specifically with people who the MAGA movement doesn’t want to lose (like relatively normal young men). But the lack of credibility most purported liberals have on this very issue means that the Democratic Party may be unable to capitalize on that unpopularity no matter how much they wave their copies of the Constitution. That just underscores the importance of establishing that credibility—which, in turn, is partly a matter of a change in personnel. And this isn’t particularly a lefts versus mods thing, by the way; Senator Bernie Sanders has a lot more credibility as a dyed-in-the-wool liberal than former Vice President Kamala Harris does. It doesn’t hurt to say so.

Second, I think this phenomenon of liberal weakness is intimately connected to the pervasive pessimism and drift on the left which Ross Douthat ably described and which Ezra Klein partly conceded in their latest conversation. Lack of confidence or conviction breeds weakness in authority; weakness in authority, in turn, engenders anxiety and fragility in those looking to that authority for guidance and leadership; and both dynamics feed and reinforce each other to produce increasing levels of hysteria and dysfunction. And this is connected to my point above about not wanting to upset the metaphorical children. Douthat predictably asks Klein about the divergence in liberal versus conservative birth rates, and I believe the divergence is multi-causal. But from my own conversations with liberal friends who are nervous about parenthood—including a number who have already become parents—one common thread is anxiety about the role of a parent as such: about doing it wrong, causing harm, not living up to the awesome responsibilities of authority. Liberals talk a lot about the need to find an inspiring cause or vision for the future; I don’t think they reckon sufficiently with the way a pervasive lack of confidence in themselves handicaps them from simply handling the present.

In any event, this difficulty in distinguishing between confident authority and authoritarianism has given a big opening to the latter. I really don’t think I’m going too far if I suggest that a lot of people who are greeting the latter’s arrival with outrage are, on another level—undoubtedly unacknowledged—also experiencing it as a kind of relief.

“the fact that institutions folded in the face of relatively weak pressure, and refused to articulate the requirements of a liberal culture to those who claimed to believe in one, showed how much weaker they would prove in the face of more serious pressure from a more powerful opponent.”

Thanks, Noah.

"I really don’t think I’m going too far if I suggest that a lot of people who are greeting the latter’s arrival with outrage are, on another level—undoubtedly unacknowledged—also experiencing it as a kind of relief."

You're a brilliant writer Noah, but this? Really? I mean, at the very least, provide some evidence please. Otherwise, I can only assume that you concluded your piece on the basis of nothing other than your own--doubtlessly very well informed, but still just--vibes.