A Solon, a King, or a Tyrant?

Do Trump's strongest ideological supporters agree on what they want him to be?

A have a guest essay in The New York Times this morning about where the blizzard of executive actions is taking us, putting those actions in the context of Bruce Ackerman’s history of the American Constitution, We the People. I won’t recapitulate the whole essay here—I hope you’ll go read it there and then come back. I’ll just quote the beginning of the piece as prologue to extending the argument in a different direction:

Americans are prone to venerate our Constitution, mythologizing the founding generation as uniquely wise, and our subsequent constitutional history as a process of evolution toward an ever more perfect union.

But American constitutional history is far more fraught, its evolution a kind of punctuated equilibrium marked by mass extinction of prior forms and precedents. Each of these moments has reshaped the way our Constitution works in fundamental ways, providing a new framework for normal politics for a new era.

The scope of President Trump’s challenge to the existing constitutional order — largely through a blitzkrieg of executive orders, many of them in blatant disregard of established precedent and legislation — suggests we may be in the process of another such discontinuous and disruptive moment.

The question is whether it will transform our constitutional order fruitfully yet again, or accelerate a final degeneration into Caesarism.

For the purpose of my essay, “Caesarism” was just meant to invoke the concentration of all political power in a single individual’s hands, the consequent withering away of both the division of power and the separation of powers that are central to America’s Madisonian system. Of course, most democracies don’t have Madisonian systems, but even unitary parliamentary systems without extensive checks and balances or a federal structure place a crucial layer between the executive and the people, because the people elect the parliament, on whose support the head of government depends. That’s not the case in America, which is why I don’t think it’s crazy to describe a system where the president is overwhelmingly dominant and unchecked as a kind of plebiscitary dictatorship. Hence, Caesarism.

I think that’s precisely what some of Trump’s strongest ideological supporters wanted Trump to be: a dictator from day one. But I don’t think there’s anything like total agreement about day two, as it were. Is the intention for the American president to be transformed into a kind of monarch? Or is the intention for Trump to rule as a tyrant in the archaic Greek sense, but ultimately in order to re-establish the republic, not to end it?

Curtis Yarvin and Peter Thiel, for example, clearly think we (or at least they) would be better off dispensing with democracy and running America like a corporation, led by a CEO who is essentially dictatorial in power and who on some level both owns the state and manages it for the benefit of its citizen-shareholders. Catholic integralists like Adrian Vermeule, the great right-wing defender of the administrative state as a tool for pursuing the common good, conceive of the presidency in something akin to the late medieval and early modern monarchy, as the patrimonial father of the people and their embodiment; in an excellent piece today at his Substack, Jack Goldsmith even quotes Vermeule referencing Ernst Kantorowicz’s theory of “the king’s two bodies.” Yarvin’s and Vermeule’s visions aren’t identical by any means, but they’re compatible, and they both imply a radical change of regime.

Michael Anton and others associated with the Claremont Institute, on the other hand, claim still to venerate America’s Constitution, and to see Trump as a kind of radical restorationist figure more akin to a tyrant in the pre-Platonic Greek sense. These were figures who seized power, often from corrupt oligarchies, and exercised power outside of the bounds of law, often in the name of the demos, the people. But tyranny was not so much a form of government as an interruption of traditional forms. The state and even the polis itself, from this perspective, needs to be purged of alien ideological elements (and, potentially, of a portion of the people itself that aren’t “actually” the people”), which requires the action of a tyrant. Once that is accomplished, though, we can have our republic again—and hopefully we’ll keep it this time.

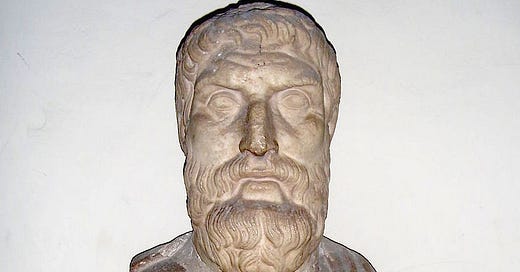

I think all of these visions are based largely on fantasy, as well as featuring a willful disregard of the role that interest would actually play—and is already playing—in these imaginary systems of benign dictatorship, whether permanent or temporary. Patrimonial rulers are far more likely simply to loot the people than to nurture them, and tyrants often come to power claiming a temporary emergency, only to quickly decide that they rather like absolute power and wouldn’t mind handing it on to their designated heirs. Solon, after all, declined to become a tyrant.

But they also aren’t all the same as each other, and that could turn out to matter. John Ganz, in an other of today’s excellent posts, details how, contrary to what might be our expectations, libertarians and corporatists could possibly have wound up on the same team, whether that team is Mussolini’s or Trump’s. (I won’t summarize his answer—go read the post.) The rubber does eventually meet the road, though, and that point of contact comes fairly quickly after the consolidation of power when the regime turns to actually the power it has consolidated. I think the same thing is true of the would-be restorationists of the “constitution in exile” and the neo-monarchists and integralists who are all currently busy justifying the consolidation of power. As soon as its time to build rather than to tear down, the differences will become manifest.

Whether we prove to be in a “constitutional moment” or not—whether Trump succeeds in effecting a radical transformation or whether he fails—the opposition needs to be alive to those differences, because they will be crucial to forging a path forward. And the path is forward, not back. As my friend and fellow Substacker emphasizes in yet another excellent post today, the one thing we now know is that we aren’t ever returning to the pre-Trump dispensation. Trump has proposed a new thesis. All new theses are beset by contradictions. That’s why—and how—they provoke a new antithesis.

I said at the top that I was going to extend my argument in a different direction, but honestly the most important thing I want my readers to take away from the above is that there’s a bunch of really worthwhile stuff to read today, all circling around this topic of the scope and meaning of Trump’s transformation. I’ll include my own piece because this is my Substack, but here’s the complete list:

“Welcome to America’s Fourth Great Constitutional Rupture” (Noah Millman)

“The President’s Favorite Decision: The Influence of Trump v. U.S. in Trump 2.0” (Jack Goldsmith)

“Gold and Brown” (John Ganz)

“Endings and Beginnings” (Damon Linker)

Thank you for this piece, and today’s article in the NYT. As a Canadian onlooker, hoping to avoid the fate of the Carthaginians, it is at least somewhat reassuring to see the gravity of the moment met with some historical perspective. Your allusion to Caesarism has reminded me that I was nearing the end of Robert Harris’ book Dictator when the US Supreme Court decision, rightly styled Trump v. United States, was announced. In Chapter 18 the book includes this fictional, but remarkably apt, speech by Cicero speaking to the Roman Senate: “Gentlemen, we embarked upon this war with Antony for a principle. The principle that no man, however gifted, however powerful, however ambitious for glory, should be above the law… The Roman Republic, with its division of powers, its annual free elections for every magistracy, its law courts and its juries, its balance between senate and people, its liberty of speech and thought, is mankind’s noblest creation. And I would sooner lie choking in my own blood upon the ground than betray the principle upon which all this stands. That is, first and last and always, the rule of law.” By Chapter 19, Cicero’s head and hands have been severed, and Augustus is on the throne as the first Roman emperor. The Trump v. United States decision marred by enjoyment of the summer months still bearing the names of Augustus and his adoptive father Julius Caesar, but I held out hope that it did not presage the arrival of an America breaking with its foundational principle of the rule of law. For the reasons you have so ably catalogued today, that hope is fading.

Thank you and very interesting. I'm guessing both that the medium term will see a thermostatic backlash against Trump, and that some fraction of his 'pen and phone' initiatives will be successful (but not all, let's say 50 percent succeed and 50 percent fail).

However it shakes out, I think the key thing is that the GOP won't go back to the days where they were content to cut taxes, reward lobbyists, but otherwise leave the administrative state apparatus permanently under the control of the liberal professional-managerial class (see: Washington DC voting 91 percent for Kamala).

They've realized: no, we don't actually have to fund this stuff year in and year out, and permanently support a galaxy of liberal 'N'GOs with our tax dollars. It's now all on the table with each new election. The future will be interesting.