What is a sandwich?

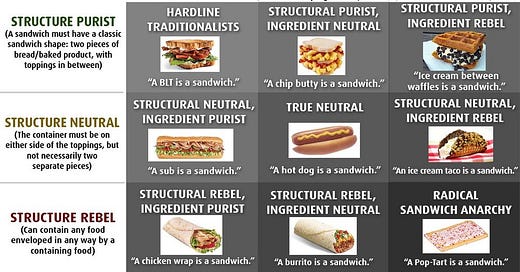

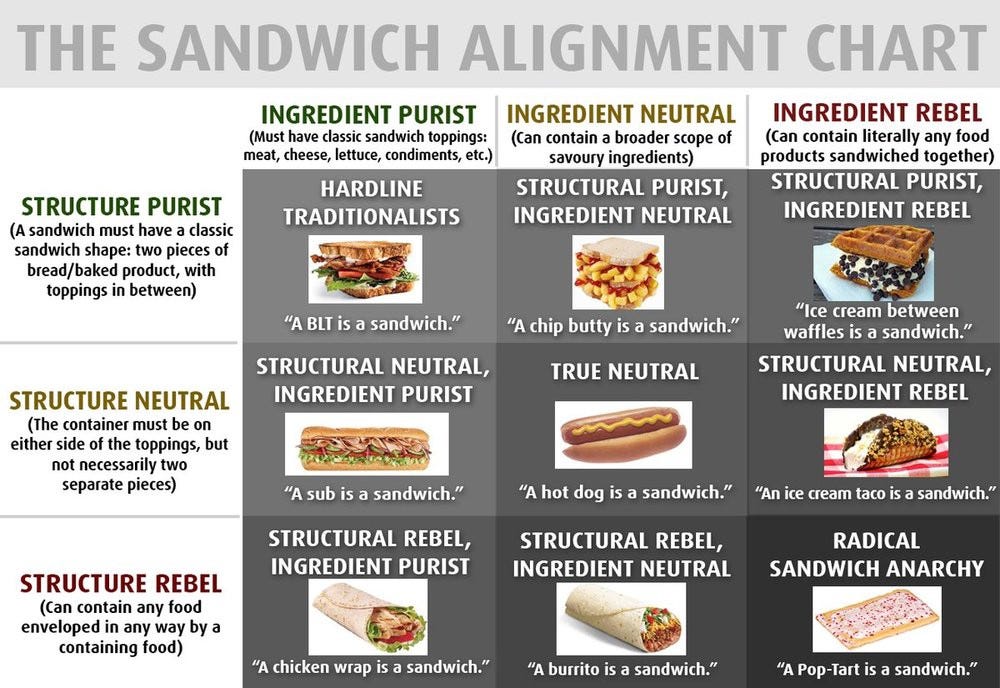

It’s a question that people have been arguing about for the internet equivalent of generations, without getting any closer to an answer. Great philosophers have been roped into the debate. Does a sandwich have a Platonic form? If so, then a hot dog is surely a debasement of that form, and should not be called a sandwich. On the other hand, if the telos of a sandwich is to deliver meat easily by hand to mouth by means of bread, then surely a hot dog fulfills that telos—and so, from Aristotle’s perspective, it is indeed a sandwich. Perhaps there is no true answer, and all the question really tells you is how traditionalist versus how radical your temperament might be—hence the chart above.

I love this debate because it confirms for me my preexisting inclination towards linguistic pragmatism. There is no essential telos of a sandwich and no ideal form of a sandwich, or at any rate these things are at best peripherally useful for deciding what the word means. “Sandwich” is just a word we use, and the question about what it means should properly be answered by asking how we actually use it, and what we successfully communicate thereby. From a study of that usage, we can try to back into a definition—but that’s what the definition is: not a fixed essence but something that will inevitably evolve as usage evolves. For it to mean something, though, it has to communicate something predictable. It can mean different things at different times, even different things in different contexts, but if, when you use it, nobody can ever be sure what you are talking about, then it has lost its meaning.

So how do we use the word, “sandwich?”

Per the chart above, it is very clear that the nature of the ingredients are not crucial to the concept based on how we use the word. Sandwiches do not have to contain savory ingredients; a jelly sandwich is unquestionably a sandwich. They don’t have to be made of bread; a submarine sandwich is clearly a sandwich even though it's made from a roll. Making a sandwich is not necessarily an alternative to cooking; a grilled-cheese sandwich is a sandwich. Nor is it a main course; an ice cream sandwich made of two cookies with ice cream in the middle is a sandwich—“sandwich” is right there in the name. And while sandwiches as we usually describe them are made of food, we can use the word intelligibly outside of a culinary context. When two of Lisa's best friends hug her from opposite sides and scream “Lisa sandwich!” everyone involved understands that this is correct usage. No one would be confused.

From this we might infer that the essential quality of sandwich-ness as it is used socially is the process of sandwiching—of pressing something between two other things that are either of like kind or which are two parts of a previously unified whole. If that’s right, and we’re backing into a useful definition, we should be able to test it by seeing whether it excludes some things that are, indeed, not sandwiches. Can we do that?

I think so. Is a burrito a sandwich? Well, if someone found Lisa in the morning completely enveloped in her sleeping bag, would they say, “look: it's a Lisa sandwich!” No, they wouldn’t. Indeed, if they said that, people listening to them would be confused, and wonder whether there were two other people in the sleeping bag with her, or if she was lying between two sleeping bags. But if they said, “look: it's a Lisa burrito!” everyone would understand what was meant. This confirms that when we speak we use “burrito” as a category distinct from “sandwich.” By similar means, we can exclude pop tarts, ravioli, bao, and other foods dubiously put forth as deserving of being categorized as kinds of “sandwich.”

It seems like we’ve very quickly backed into a definition that can conclusively establish what is and is not a sandwich. Yes?

Well . . .

Behold: the open-faced turkey sandwich. Not only is it not an example of something that has been sandwiched—nothing is pressed between two things—but because the gravy will have soaked into the bread it will no longer even be possible to assemble the object into a proper sandwich by pressing the two open sides together and picking it up. You have to eat it on a plate, with a knife and fork—precisely the procedure that, from a teleological perspective, the sandwich exists to obviate. This is, quite literally, a sandwich which is not and cannot become a sandwich.

Yet, go to any diner, and you can order one of these, and it will be called a sandwich—as with the ice-cream sandwich, the word is right there in the name. It’s clearly not a sandwich—and yet we call it a sandwich, and so it is one. How can this be?

The right answer, I think, is to approach it from the perspective of history: not how can this be, but how did this come to be. Approached that way, I think the answer isn’t complicated. These are classic sandwich ingredients—bread, meat, condiment—that look like they are going to be assembled into a sandwich. We could, in fact, assemble them into something that approximates the “Platonic form” of sandwich if we so desired. Instead, they are diverted into an alternative arrangement that is not a sandwich. They are not simply any arrangement of ingredients; they are an arrangement of sandwich ingredients into a non-sandwich form. The term we’ve come up with to describe this arrangement is marvelous in its clarity and economy: it preserves the relationship with sandwich-ness, but also underlines the fact of its differentiation at precisely the point that essentially defines a sandwich. Hence: the open-faced sandwich.

Are there other examples where such a historical approach might clarify what we do or don’t call a sandwich? I believe there are. Consider, for example, the felafel sandwich.

On its face, this is a peculiar usage. We’ve established that a burrito is not a sandwich because nobody would look at Lisa in her sleeping bag and see her as analogous to a sandwich. But you don't make a pita sandwich by pressing felafel between two separate pieces of pita; rather, pita is a kind of bread that forms a pocket into which food is inserted. Lisa in a sleeping bag is a lot closer to a pita sandwich than she is to a burrito. But she’s not a sandwich. Why, then, should a felafel in pita be a sandwich?

I suspect the answer is something like the following. When pita started to become a more common food in America, both the buyers and the sellers had to categorize its use. The simplest way was by analogy: a pita is a kind of bread from which you can make something like a sandwich by putting meat and vegetables inside and pressing the sides together to eat it by hand. If you want to understand its telos, “sandwich” communicates it nicely. It might best be analogized to a marsupial sandwich, bearing the same relationship to traditional American sandwiches that marsupial mammals do to mammals that gestate in the more familiar mammalian manner.

That makes sense to me. But it raises an obvious follow-up. If pita bread can be used to make a sandwich even though you don’t sandwich anything between two pitas, then why isn’t a burger a sandwich?

It certainly seems like it should be. It’s very close to the Platonic form, in fact: meat sandwiched between two halves of a bun with toppings and condiments, eaten by hand. A burger is nothing more than a hamburger steak sandwich. Why, then, don’t we call it that?

Well, we used to. Before there were burgers, there were hamburgers; and before there were hamburgers, there were hamburger steak sandwiches. What happened is that, over time, the hamburger steak sandwich became so popular and distinctive that it outgrew the “sandwich” category to become a category of its own. In so doing, it evolved to become something much larger than its original definition. Some restaurants have an entire burger section on their menus; some describe themselves as burger restaurants. We now describe as types of “burgers” comestibles that may look like hamburger steak sandwiches, but that are not made with hamburger meat (meaning: ground beef) at all. They may be made with turkey, or salmon, or any number of vegetarian concoctions, including some made from . . . chick peas.

Strangely, then, if you mash up chick peas, form them into a patty, grill the patty and sandwich it between two buns, you have made a veggie burger; but if you mash them up, form them into balls, fry them, and put them in a pita pocket (which does not properly involve sandwiching at all), you have made a felafel sandwich.

Ain't language grand?

Why am I bringing all this up? Well, at Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearings this past week, Senator Marsha Blackburn asked Jackson if she could provide a definition for the word, “woman,” and Jackson said she could not. This was an obvious gotcha moment—look how far gender ideology has corrupted our language: a candidate for the Supreme Court can’t even define what a woman is!—and it’s pretty easy for all of us to go from there into our respective culture war corners and yell at each other just like we’re supposed to. I’m going to try to do something different by suggesting that we learn from the sandwich, and realize that we don’t actually experience life through definitions; rather, we back into our definitions from our experiences of life, and it’s the experiences, not the definitions, that really matter.

Human sexual dimorphism is something children discover very early. If they are breastfed (as the overwhelming majority of children are), they experience it in a primal way before they are able to form cognitive categories for that experience. And while there are of course exceptions, most human beings sort fairly neatly into that dimorphism, and we—again from a very early age—learn to sort people similarly. We don’t have to trouble with definitions; we know first, and then we abstract from that experience in order to understand it better.

So the entire debate, in the variety of contexts in which it takes place, about who “counts” as a woman is part of that process of abstraction. The question is: what is its purpose?

In the debate about sandwiches, there is no practical purpose; it’s just for fun. Nothing much depends on the question of what is or isn’t a sandwich. If you’re a restaurant, and you want to list hot dogs under sandwiches, go for it; you’ll probably have no problem. At worst you’ll prompt your patrons to waste time debating with each other whether, in fact, a hot dog is a sandwich. If you start listing milkshakes under sandwiches, you’ll undoubtedly confuse people, and might lose business as a result—but that’s literally your business. The only time it becomes anybody else’s business is when the government decides to regulate sandwiches. Then it becomes important to know what is, and what isn’t, a sandwich. (I will note that, legally, a burrito is not a sandwich.)

That’s the proper context to understand Jackson’s answer. What is a woman? Well, are we providing for women’s healthcare? Are we collecting demographic information for the purpose of assessing discrimination? Are we setting the rules for participation in women’s sports? Or for housing in women’s prisons? Legislators and administrators might reasonably answer differently in different contexts—and judges, in interpreting laws written years or decades ago, might similarly need to assess varied context before giving an answer.

Take a look at Bostock v. Clayton County, for example. The decision, written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, prohibited employment discrimination against gay or transgender individuals, but it did not do so on the basis of defining sexuality or gender identity. Rather, the ruling is grounded in the assumption of sexual dimorphism built into the law in question. If an employer fires someone female who is in a romantic and sexual relationship with another woman, or if an employer fires someone biologically female who identified publicly as a man, Gorsuch says that constitutes discrimination on the basis of sex, because if the individual in question were biologically male, and behaved in the same manner, they would not be fired. In other words, in the context of Bostock, transgender men are women and transgender women are men.

Whether you like Gorsuch’s ruling or not, it’s important to recognize that he was being legally parsimonious in reasoning this way, because the alternative was to recognize sexuality and gender identity as legal categories, which, arguably, ought to be the legislature’s job. Regardless, the reason he had to come up with some reasoning on the question is that new facts create new legal questions that judges will have to opine on, and it isn’t right to prejudge the answer without knowing the facts and circumstances of the case. When Jackson said she couldn’t define a woman, she was avoiding prejudgement, expressing an awareness of that complexity as it pertains to applications of the law, and declining to define the meaning of a word out of context. I think that’s a sign of wisdom, because the law is averse to the kind of fuzziness that is natural to language. It requires a precision that is fundamentally unnatural.

But we’re not lawyers. We don’t have to talk like them, we don’t have to think like them, and we don’t have to take our cues from them when we think or when we speak.

I’m part of the “Free To Be You and Me” generation, and the whole point of that album was that men’s and women’s destinies were not limited by cultural assumptions about what a man or a woman can grow up to be. A man can be a cocktail waitress! A woman can be a fireman! (She can also go bald, a fact that slapped the entire world in the face just this past weekend.) The jury is still out on the degree to which men and women have natural inclinations toward certain occupations and activities—I think it’s foolish to assume there are no natural differences on average, but also unjust to presume natural difference when both cultural expectations and invidious discrimination have so obviously played an important role throughout history in men’s and women’s choices—but the point of the album wasn’t that men had to be cocktail waitresses, just that they perfectly well could if they wanted to. Wanting to be a cocktail waitress wasn’t wrong for a man, and didn’t make you something other than a man. Your identity didn’t determine your destiny, nor vice-versa.

It’s possible to talk about gender identity similarly today, as something that shouldn’t be limited by biology, though it’s far from a universal practice. What I mean by that is, you can readily find people saying, for example, that a woman can have a penis, because the category of transgender women includes people who haven’t had bottom surgery, and never intend to. Similarly, not having a penis doesn’t make you not a man. Statements like these don’t say what a woman or a man is—they just say that it’s not defined simply by genitalia or chromosomes.

The obvious question, though, is that if we’re not defining gender by sex, then what are we defining it by? And the usual answer is that gender isn’t about what’s between your legs but about what’s between your ears—that is to say, if you identify as a woman, then you are a woman.

People have made a variety of different objections to that idea, but the one that hits home strongest to me is that, for a great many people, this is actually false to their experience. Lots of people—most, I suspect, especially people over 40—have never gone through the experience of “identifying” as a particular gender. They just are who they are. It’s not that they’ve never felt alienated or dissociated from their bodies, or never felt both “feminine” and “masculine” feelings—nearly everyone has had those kinds of experiences (I certainly have). Those experiences just didn’t define anything about their identities. They were experiences they had; they didn’t define who they were.

I’ll give you an example. A woman I’m close to, whose daughter identifies as nonbinary, told me that she never really felt like a woman until she got pregnant. That’s the moment that clicked everything into place for her. I suspect she’s not alone, and that her experience probably gives her some useful insights into her daughter’s experience, though I also wouldn’t presume that their experiences will be identical. Regardless, if we’re in the business of definitions, what was she back before she got pregnant? It’s one thing for her to say that she didn’t feel like a woman until she got pregnant, that she felt alienated from her body and so forth. That was her experience. For someone else to say, by way of defining what a woman “is,” that she wasn’t a woman until she got pregnant . . . well, there are a lot of possible words for that kind of talk, but I can’t think of any that are nice.

Which seems to put us at an impasse. If you define “woman” as someone of the female sex, you’ve defined a bunch of transgender women as men and a bunch of transgender men as women, which they understandably view as an affront. If you define “woman” as someone with a female gender identity, you’ve defined a bunch of women as “cisgender” without asking them whether that label is true to their experience at all (and it very well might not be). That’s also an affront. What is to be done?

I want to suggest that one very real option—for ordinary people if not for lawyers—is not to worry about definitions, anymore than we do about defining a sandwich.

There’s no definition of “sandwich” that makes sense of saying a burger is not a sandwich but a felafel in pita is a sandwich. There’s no definition of “sandwich” that makes any sense of an open-faced turkey sandwich at all. And it doesn’t matter: we still know what we’re talking about. Similarly, I think if you walk around with a model in your head of what a woman “is” that is rooted in sex rather than gender, and isn’t actually very clear about the distinction, but that accepts the existence of exceptions and accepts transgender women’s self-identification, you’re going to have a very hard time writing down a coherent definition of the word, “woman.” But you should have an ok time getting along in the world and understanding who people are. Indeed, you might have a better time than folks who have decided to take a strong stand that gender ideology is completely true—or completely false.

As someone who tries to be a good citizen and a good neighbor, I believe those ought to be the goals—not just getting along with people, which you might do by minding your own business and not making trouble, but understanding who people are. That requires more than keeping your head down; it requires communication, a willingness to speak and a willingness to listen. It requires asking questions and being asked questions; it rarely requires hard and firm answers.

Most of all, communication is facilitated not by thinking and speaking like lawyers, but by thinking and speaking naturally.

Flexibility simply won't work. If you ban discrimination on the basis of "gender identity" (as the Equality Act would), and you don't define "gender identity" (it currently has no specific legal definition and the Equality Act also does not provide one), then anyone can claim to be any gender at any time for any length of time. A man can, for example, enter a womens' professional sporting event (with prize money), and it would be illegal to stop him, unless and until a more restrictive legal definition of "gender identity" is passed into law or is imposed by the courts. A man can enter any womens' locker room and ogle to his heart's content, and it would be illegal to remove him.

That's what "flexibility" gets you.

While I agree that the rancor over KBJ's response was overwrought, I don't think it can be defended on the ground you've supplied, because the fact of the matter is that she *didn't* say, "I don't know, it might depend on the statutory scheme at issue." She said, "I don't know, I'm not a biologist." So, she wasn't making any claim that this is a term that might have some fuzzy definitions depending on the context. She, at least implicitly, acknowledged it has a specific definition, but professed not to know it.

That said, I am not sure I can think of a statutory scheme that uses the word "woman." The more common formulation is "on the basis of sex." So the better question would have been about defining the word "sex," not the word "woman." That could have made for an exchange even more cringy than the one we were treated to, though.