A Meme War With Real Bullets

Thoughts on Operation Absolute Resolve

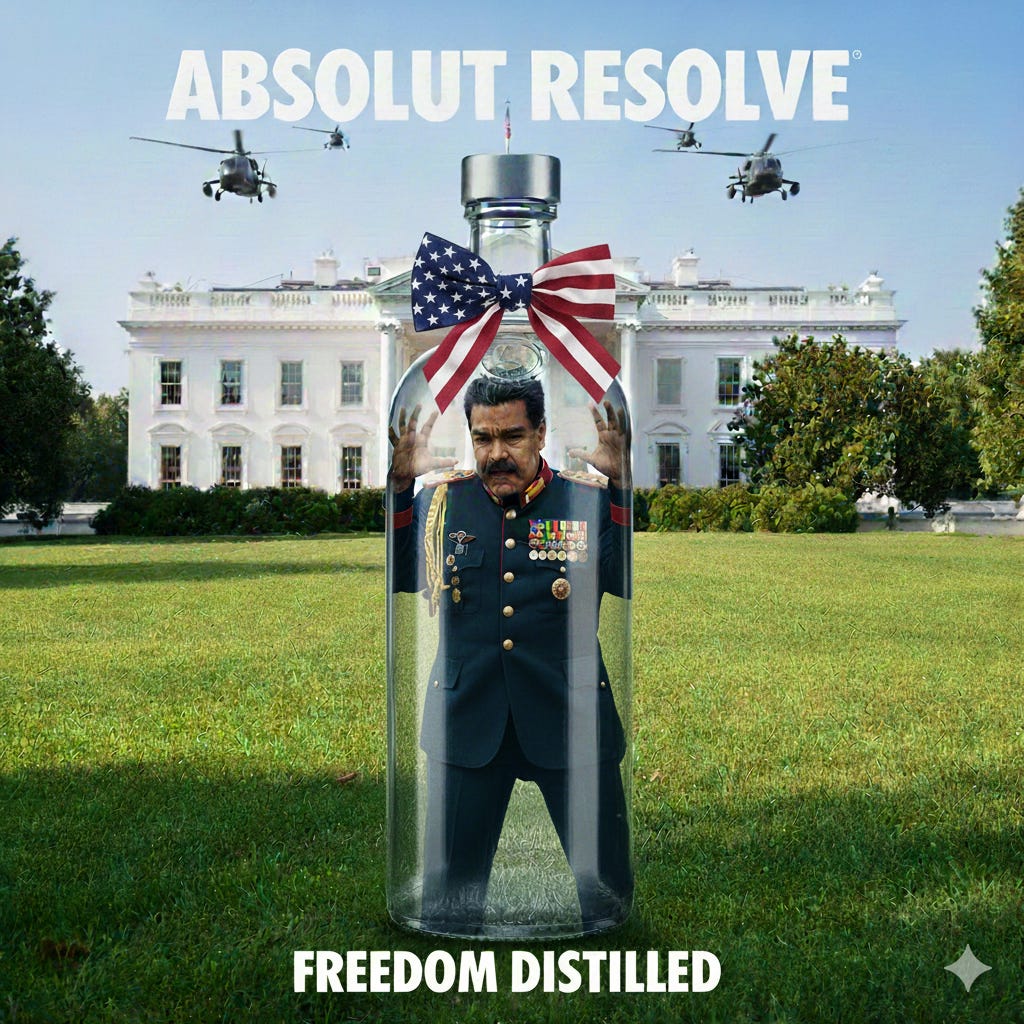

This was my first A.I. image made with Gemini. Do I have a future as a regime propagandist?

As I’m sure everyone reading this knows, on Saturday the United States abducted President Nicolás Maduro and his wife from Venezuela to face charges in the United States. My immediate reaction upon hearing the news was to think of Operation Just Cause, America’s intervention in Panama to capture General Manuel Noriega and bring him to the United States to face similar charges. Many other commentators made the same connection (and posted about it more quickly). There are a number of differences between the two situations—Noriega wasn’t actually the head of state, Panama bizarrely declared war on the United States before we invaded, we actually did invade the country in force, and we installed Guillermo Endara, the rightful winner of the country’s last presidential election (which Noriega had annulled) as the new head of Panama’s government—but the two operations were similar in that both were probably illegal under American law, and almost certainly illegal under international law, and both also triggered immediate alarm about American intentions within the region.

The most important comparison between the two conflicts, though, is that in neither case was it entirely clear why we did what we did. Noreiga had been an American intelligence asset for years before our relationship soured, but he posed no significant threat, not even in the sense of being a particularly important part of the drug trade. We didn’t really need to remove him, and if the invasion had been unsuccessful it would have been a fiasco for the new president. Similarly, Maduro was clearly an annoyance, but the main way in which he posed a threat was by destroying his own country, triggering an exodus of something on the order of a quarter of the population. We haven’t occupied the country, so we can’t actually “run” it as President Trump claims we will, and the current plan appears to be to have Maduro’s own Vice President assume his office, on the assumption that she’ll play nicer with us than he did. But what will “play nicer” really mean? Both the President himself and other administration spokespeople have repeatedly invoked the importance of Venezuelan oil as a justification for the operation (which has outraged many commentators with its crassness), but it’s not clear that any major international oil companies even want to invest the amount necessary to ramp up production, certainly not with oil prices down below $60/barrel. Nor is it clear that if they did it would be good for the American economy, since we are now an oil-exporting nation. Abducting a foreign leader to give American oil refineries more business is a laughable idea. Maduro was a bad guy and a truly terrible leader, but what American interest was supposed to be advanced by removing him, however spectacularly, remains obscure.

So it’s hard to avoid the feeling, as John Ganz suggests at the end of his own piece on the subject, that the operation was undertaken primarily for its propaganda value, both internal and external (as, in truth, the Panama invasion may have been as well). Internally, an operation like this allows for the creation of memes like the one I generated above, and leaves critics in the position of carping in contradiction, saying on the one hand that we shouldn’t have done such an unneighborly thing, and on the other hand that we needed to take even more aggressive action (like actually occupy the country to restore democracy) for the operation to have been morally justified. But the more important propaganda value is external. America has demonstrated to countries around the world both our ability and our willingness to do something like this, and we are telegraphing our eagerness to do it again. If you can’t defend yourself effectively and you annoy us enough, we might just take you out. If I were Claudia Scheinbaum, I’d be treading very cautiously. Heck, if I were Mette Frederiksen I would be too.

But I would also be trying to figure out how to defend myself. That might mean building economic relationships with countries (like China) that have proven less capricious than America, or tightening security to prevent the kind of CIA infiltration that was crucial to the success of the operation against Maduro, or developing asymmetrical retaliatory capabilities such as the Houthis have deployed so effectively, or, in the extreme case, acquiring an independent nuclear deterrent. (We haven’t kidnapped Kim Jong Un yet, I note.) The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must—so the weak, if they want to suffer less, must find ways, consistent with their weakness, to reduce the scope of what the strong actually can do to them, or what the strong would be willing to do given the risks and costs they would have to face. None of those responses serve American interests.

Which is why America, the strong in this scenario, needs to remember that an impressive tactical operation is not the same thing as a strategy. In its audacious conception and meticulous execution, the other operation that Operation Absolute Resolve reminded me of (besides Operation Just Cause) was Operation Grim Beeper, the nickname for Israel’s spectacularly successful infiltration of Hezbollah to plant exploding beepers throughout their command, crippling the terrorist group upon detonation. That operation immediately changed Israel’s strategic environment, removing much of the threat from the north, and changed it even more dramatically when Hezbollah’s absence from the battlefield enabled the rapid overthrow of the Assad government in Syria. But as of yet, I don’t think Israel has done much of anything to use this transformed environment to secure any lasting strategic gains. It seems likely to me that the United States will behave similarly, that we will thump our chest and crow about how nobody better mess with us, then act surprised when, down the road, we discover that our position has deteriorated.

I hope I’m wrong. For all that I loathe this administration, I loathe Venezuela’s regime much more, and I wish my country’s good, so I don’t want this operation to turn out horribly, for America or Venezuela. The invasion of Panama was the most dramatic and direct intervention in the internal affairs of a Latin American country in decades, but it was not followed by any similarly aggressive acts in the Western Hemisphere. And while the people of Panama mourned the destruction of the invasion, they prospered in its wake. So I can hope the same is true of Operation Absolute Resolve: that it proves surprisingly successful, and is not repeated.

But on the larger world stage, the invasion of Panama did presage a far more aggressively interventionist America. In the parlance of our time, it demonstrated that you can just do things, and, as Scott Sumner ably delineates, its success encouraged us to do more and more things, some of them catastrophic. I do not look forward to finding out what catastrophic adventure this administration will be emboldened to undertake in the wake of success, and I really don’t look forward to the nemesis that hubris will inevitably conjure.

I appreciate that you focus on the precedent it sets for America rather than for other nations. I'm not worried about this embolding Putin - they don't come much bolder. I do worry, constantly, that Trump's bullying instinct will overcome more of his proclaimed anti-interventionist policy. Which does remind me: his complaint about intervention was always that we weren't getting ours, not that we were unduly dishing it out.

One line of analysis I’ve been seeing a lot in Latin American commentary goes roughly like this: even if redeveloping Venezuela’s oil sector would require massive investment and time, the strategic value isn’t short-term profits but long-term control. As Middle Eastern supply becomes more politically exposed (Red Sea, Hormuz, BRICS alignment), having Venezuelan heavy crude available gives the U.S. greater leverage over prices and supply, and reduces dependence on chokepoints controlled by rivals. In that frame, this isn’t about immediate gains but about positioning for a future conflict environment.

I’m curious how you think about that argument — not as rhetoric, but as a proposed strategic logic.