A Killing In Context

Renée Good's death was tragic but far from unprecedented; the government's response has been something else

The killing of Renée Good is obviously a horrible tragedy. On its face, however, is not an unprecedented one, nor one that in and of itself need prompt outrage and despair. Police officers and other armed agents of the state sometimes kill civilians. Most of those homicides are justified, but sometimes the preponderance of evidence suggests that the use of force was unjustified and/or that those killed were innocent of any serious wrongdoing. Poor training and/or recognized deficiencies in the offending officers’ character are frequently factors in the most troubling killings; sometimes this extends to the possibility of bias or other malicious intent having played an important role in their actions. I haven’t forgotten the names Amadou Diallo, Breanna Taylor or Philando Castile, nor have I forgotten Allison Krause, Jeffrey Miller and Sandra Lee Scheuer.

Neither is it unprecedented for angry members of the community of the victims in these cases to worry that the political system will close ranks to keep justice from being done. The officers involved may coordinate their stories; the higher-ups in the chain of command may stonewalls efforts at investigation; prosecutors may refuse to bring a case or, if forced to do so, may subtly sabotage their own efforts so that the defendants are acquitted. That is certainly not what always happens—justice has been done over and over in many such cases, both when malefactors are prosecuted and convicted and when the officers responsible for a killing are deservedly acquitted or, after investigation, never prosecuted at all. But sometimes justice isn’t done and sometimes the reason it isn’t is that the system quietly made sure it wouldn't be.

All of the above suggests that the killing of Renée Good could be assimilated to a history of law enforcement that has its inevitable tragic side. The killing of Ta’Kiya Young bears a resemblance to Renée Good’s in a number of ways, and in that case the shooting officer was charged and acquitted. But there are several ways in which this killing is harder to assimilate, which suggest that the most important context is not the history of similar events but the distinct dangers of this moment.

It is normal and appropriate for government officials to call for calm, to express their confidence in law enforcement in general, and to assure the public that the only just approach is to let the system to take its course. It is something quite novel and wildly inappropriate for the President, the Vice President, the Director of Homeland Security and other federal officials to repeatedly and unequivocally prejudge the case, much less to promote easily-refuted falsehoods so as to make that case seem cut-and-dried in the officers’ favor.

It is normal if regrettable for local government, in investigating incidents of this sort, to put its thumb on the scales on the side of local law enforcement—which is why, sometimes, the federal government winds up getting involved as well to protect the civil rights of the victims. It is something quite novel and, to my mind, quite inappropriate for the FBI to block local law enforcement from investigating a homicide committed within their jurisdiction, and behave more generally like the duly-elected governments of an American city and state are presumptively hostile to federal law enforcement officials rather than partners in a federal system of government.

In 2020, after the killing of George Floyd, activist groups behaved as if that killing was unquestionably criminal murder. They comprehensively prejudged the case, and the protests and riots that followed cowed elected and appointed officials around the country into effectively ceding their authority for a significant period of time. This was not a civically healthy development; it predictably stoked a reaction, which was one of the background causes of the return of Donald Trump to the White House, even though he chaos of 2020 happened on his watch.

Now, though, the United States government is behaving like those activists, but in reverse. It is saying, explicitly, that all you need to know to establish the rights and wrongs of this incident is who was involved; any evidence gets filtered through that lens, interpreted accordingly, and declared to be the only obvious way to understand the matter, with dissenters declared to be enemies of truth acting in manifestly bad faith. Keyboard warriors on both sides do this all the time, behavior that sometimes spills out into real life, and it’s bad when either side does it. But it is a completely different situation when government officials behave this way. The Department of Justice has been so explicitly politicized in the past year that no impartial observer can be confident that it will investigate this killing in a forthright and fair manner. And the profligate use of the pardon power by President Trump not to redress injustice but to reward political supporters means that there’s every reason to assume that, in the unlikely event that an indictment were ever forthcoming, the killer would be indemnified from prosecution and punishment.

That change in our government is part of the background to protests of the sort that Renée Good was engaged in, and it’s part of the background to the protests that have been launched in the wake of her killing. But that context needs to be assimilated into the act of protesting itself. In Iran right now, protests are happening all across the country, expressing widespread public outrage and disgust at the regime. The regime is cracking down violently, and in that context the most important target of the protests is those who will have to execute that crackdown, as well as their commanders. If the regime can no longer count on its own instruments of repression to do their jobs, it could quite suddenly collapse; but if it can count on them to do their jobs, then the protests will likely be crushed, as they were in 2009, 2018, 2020, and 2022. I hope this time is different. But if it is, the reason will be that the military and security services decide they no longer want to kill their neighbors at the behest of the regime.

The United States is not Iran. We still have robust political competition; we still have largely free and fair elections; we still have a largely free press; we still can peaceably assemble and protest. Protest, in the United States, is part of normal politics. And while Republican officials are generally terrified of crossing President Trump and his supporters, they are not insensible to other political risks they face. That’s why seventeen Republicans in the House voted to restore Obamacare subsidies and five Republicans in the Senate voted for the war powers resolution limiting further military action in Venezuela without congressional approval. Given that reality, the most important purpose of protest in the United States is to create political risk for officeholders whose support is important to the continuance of the activities being protested against.

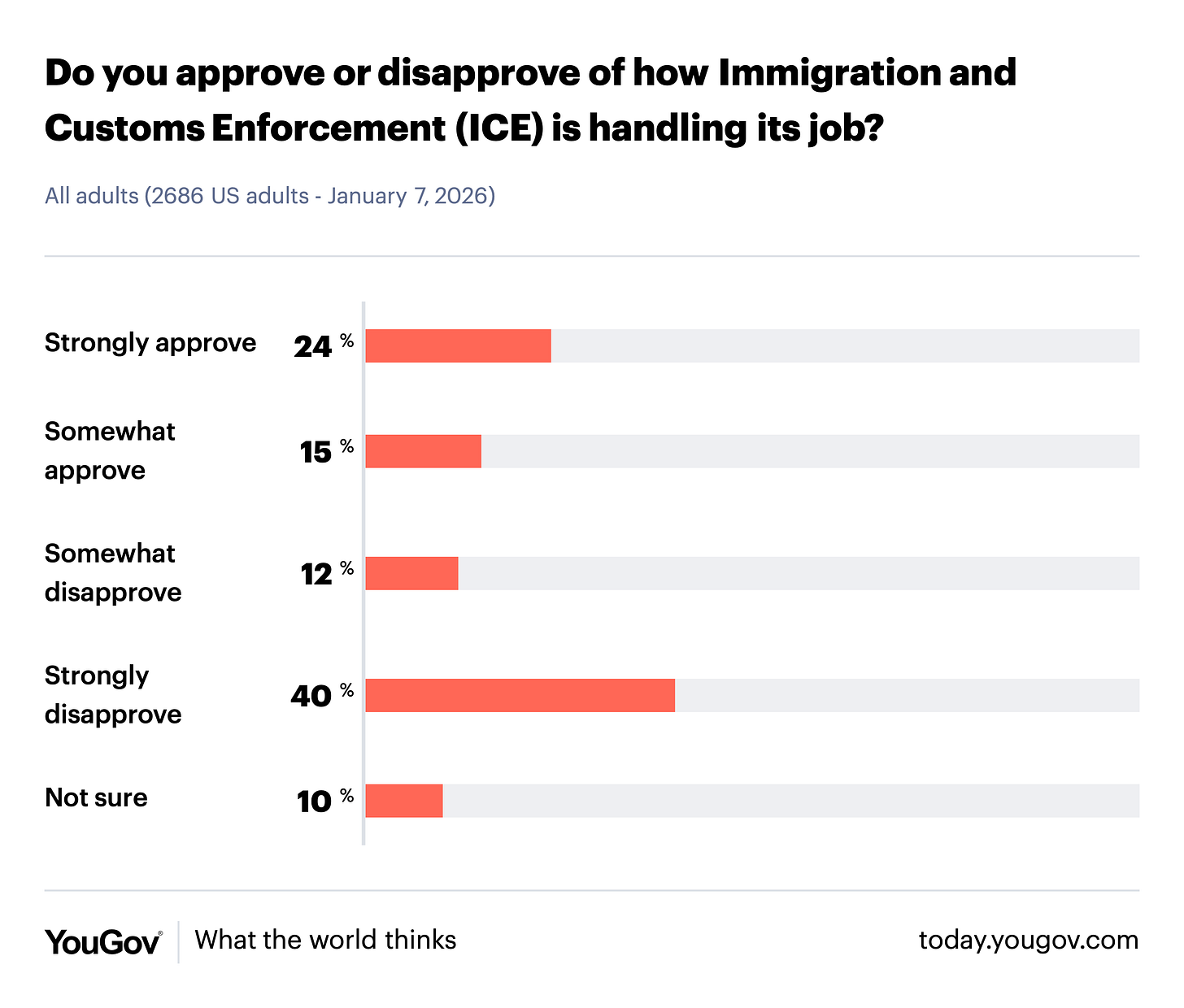

According to a YouGov poll, here’s what Americans thought of ICE’s behavior on the eve of Renée Good’s killing:

A majority of respondents disapprove, and a plurality of respondents strongly disapprove; only a quarter of respondents strongly approve. That’s not a lot of support; ICE’s tactics were alienating Americans well before the killing of Renée Good. But it’s not overwhelming opposition either. I suspect that 40% of Americans strongly disapprove of just about everything the Trump administration does, and that such a level of strong opposition is perfectly consistent with remaining politically viable in our highly polarized times. If protests aim to actually restrain ICE, then they need to move more people from the 37% who weakly approve or disapprove or have no opinion into the strong disapproval category.

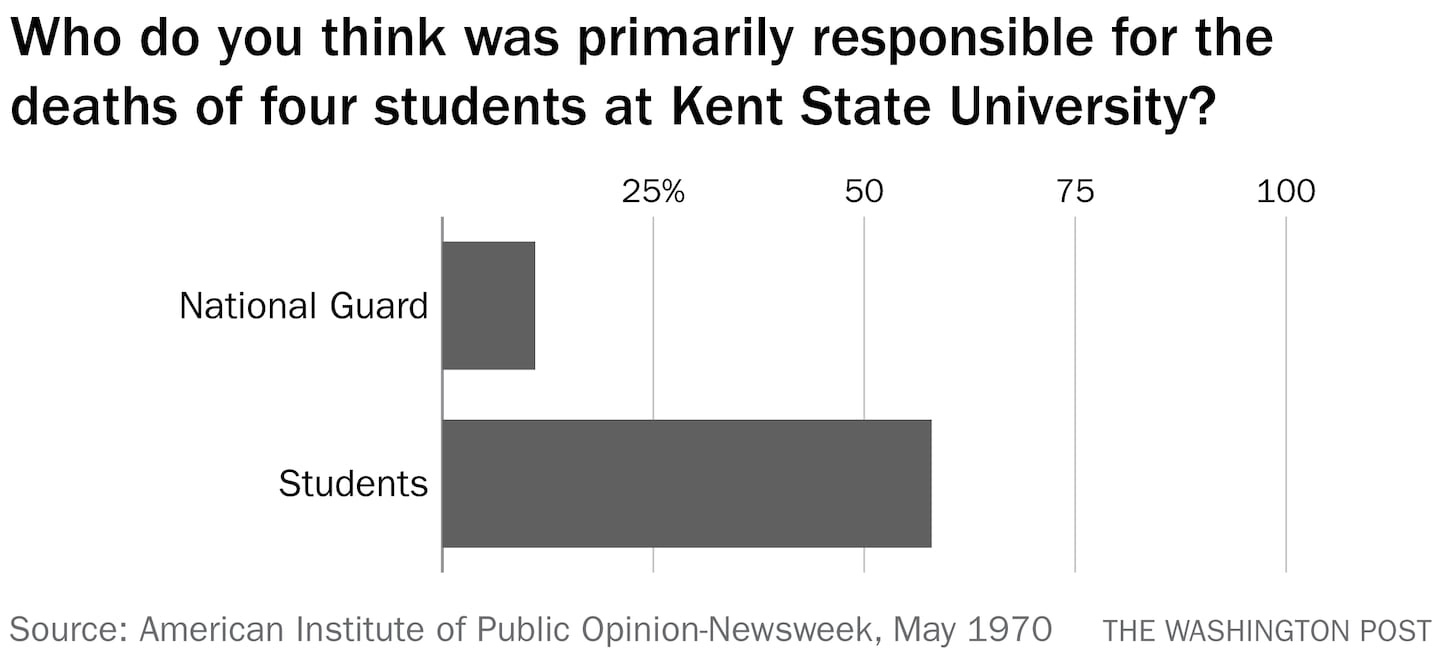

Interestingly, that level of disapproval is also roughly comparable to views of Americans on the Vietnam War around the time of the Kent State massacre. In an April, 1970 Gallup poll, a bare majority of Americans deemed our involvement in Vietnam a mistake. Yet this was the initial public response to the shootings at Kent State:

In other words, even as Americans were turning against the war, they were more inclined to trust members of the National Guard than the students they fired upon, and didn’t want American foreign policy to be decided by protestors.

I suspect that the public will prove far less inclined to blame Renée Good for her death than Americans in 1970 were to blame the students at Kent State—but the divide might look similar to the divide over ICE, which is to say, like our political divide more generally. But the rhetoric of the administration and its supporters is plainly aimed at conjuring that era’s reaction into being, and in that sense they clearly see the death of Renée Good as an opportunity and not just a danger. Why? Because disorder serves the interests of a political movement that identifies itself with order, and that is eager to dispense with law to get it. So protest has to be conducted in a way that prevents that from happening, and with a view to pushing the scales of public opinion the other way.

Meanwhile, we desperately need to restore public appreciation of neutral and impartial justice as essential public goods. It is a sad fact that support for liberal democracy is very weak right now, not only in the United States but across the globe. The Democratic Party has repeatedly cast itself as its defenders, and this has consistently failed as a political message—whether because too many voters don’t believe the Democrats are actually committed to liberal principles, but instead use them as a mask for partisan power grabs and promoting an illiberal left-wing ideological agenda, or because too many voters simply do not see the defense of liberal democracy as nearly as important as controlling inflation or other pocketbook concerns. But that’s also part of the context within which protest is playing out. Protesters cannot confidently lean on a common belief in liberal principles to move the public in their direction. They must, somehow, also build that belief up.

Noah, thanks for this. It is helpfully orienting, as your work always is.

For what it’s worth, I do not know a single committed Republican voter who thinks that even one Democrat is “actually committed to liberal principles.” They are told every day by people they trust that the opposite is true. And it must be said that the Democratic party has done a great deal to encourage a belief in their illiberalism, but even if the party made an absolute commitment to restoring their bona fides, news of it wouldn’t penetrate the right-wing media containment field.

It’s interesting to note, not what left or left-ish media say about the Trump administration, but what the administration says about itself:

1) That the President is not bound by national or international law but only by his own “morality” (the President himself);

2) That in governing the only things that matter are “strength ... force ... power” (Stephen Miller);

3) That because ICE is effectively serving as the executive branch’s police force, an ICE agent can kill anyone at any time for any reason and have “absolute immunity” from consequences (the Vice-President).

And roughly 40% of Americans are totally fine with all this. You could argue, of course, that many of them don’t know the specific points I have just noted, but does anyone believe that if they did know they would change their views? That would change nothing — it might even confirm some people in their support. In fact, if Trump were to declare tomorrow a state of emergency in which all elections are suspended for the indefinite future, and YouGov polled people on what they thought about that, I doubt that the numbers would be much different than they are in the poll about ICE’s actions.

So I think those of us who would like to live in a relatively free country instead of a police state should (a) thank God that the percentage of Americans who *want* to live in a police state is less than a majority and (b) understand that those 40% are unreachable by appeals to evidence or morality or the constitution of this nation.

Then the question becomes: How to engage the 22% who only somewhat disapprove of what ICE is doing or don’t know what they think? For those who would wish to see this regime constrained and (ultimately) defeated, that’s the only question. And I think that as you hint in your post, the means by which this engagement could be generated largely concern moral formation.

This is a measured and thoughtful article. However, this needs to be discussed:

“…which was one of the background causes of the return of Donald Trump to the White House, even though he chaos of 2020 happened on his watch.”

Given that the protests largely occurred May-October of 2020, during the height of the campaign for the White House, which he notably lost, this is a pretty large assertion to make without evidence or citation.

You are saying that the protests didn’t propel him back into office at the peak of their salience, while the Trump campaign and it’s associated dark money groups were spending hundreds of millions of dollars to increase the salience to the election. But four years later, when the Trump campaign and it’s superpacs were running primarily on economics, immigration and queerphobia, then it was part of his return?

Especially in a piece with so much opinion polling cited, this is a claim in need of further discussion.